Updated | On March 24, a convenience store owner in Glasgow, posted a status update to his Facebook page: "Good Friday and very happy Easter especially to my beloved Christian nation." Asad Shah continued, "Let's follow the real footstep of beloved holy Jesus [Christ]...and get the real success in both worlds." To Shah's Facebook friends, the exuberant message was not much of a surprise. Shah, who identified as a Muslim, was a member of the Ahmadi religious community. The Ahmadi faith is generally tolerant of other religions—and Shah was particularly welcoming. In December, a neighbor tells Newsweek , he gave every visitor to his shop a personalized Christmas card.

That same day, however, an unwelcome visitor was on his way to Shah's shop. The man was later named by his lawyer as Tanveer Ahmed, an Uber driver from the English city of Bradford. According to witness accounts provided to journalists, Ahmed, who is a Muslim, entered the shop, repeatedly stabbed Shah and left him to bleed to death, to the horror of passersby. While blood pooled around Shah, Ahmed calmly waited for the police. A later photo shows him sitting on a bench at a bus stop as three officers stand guard. "This all happened for one reason and no other issues and no other intentions," Ahmed said in a statement issued by his lawyer on April 6. "Asad Shah disrespected the messenger of Islam the Prophet Muhammad peace be upon him. Mr. Shah claimed to be a prophet."

The death of Shah shocked many in Britain—it is believed to be the first time a Muslim in the U.K. has killed a member of the Ahmadi faith because of the victim's beliefs and statements—but members of the British Ahmadi community say the crime was a culmination of a campaign of intimidation against them. Some Muslims believe Ahmadis are not true Muslims. Ahmadis believe that the second coming of Christ has happened in the form of their prophet and founder, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, an Indian spiritual leader who died in what is now Pakistan in 1908. In this they differ from most other Muslims, who believe Muhammad was the last prophet and that the second coming of Christ is yet to happen.

The difference might sound slight—Ahmadis still believe in the fundamental message of Islam, that there is no God but Allah and Muhammad is his messenger—but for some Muslims the Ahmadis' beliefs are blasphemous. Radical Islamists, mainly in Pakistan, have murdered hundreds of Ahmadis and attacked many more because of what they see as an unforgivable doctrinal deviation. Many Ahmadis have sought safety in the U.K.—home to the faith's headquarters since 1984—but their sense of security has been profoundly shaken by the killing of Shah.

In the wake of Shah's death, the current leader of the Ahmadis, Caliph Mirza Masroor Ahmad, said that unless the U.K. government did more to combat anti-Ahmadi prejudice, "extremists will create the same havoc in the U.K. as they have in Muslim countries."

British Prime Minister David Cameron said after the attack that religious leaders in Britain should work together to prevent further violence. "What we are seeing is a small minority within one of the great religions of our world, Islam, believing that there is only one way, a violent extremist way, of professing their faith," Cameron said.

The Ahmadis, who are believed to number between 10 million and 20 million globally, began to face concerted persecution in Pakistan in 1974, when the government ruled that they were not Muslims. (Pakistan is still home to the world's largest population of Ahmadis.) In 1977, the head of the army, a devout Muslim named Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, seized power in a military coup and began enforcing Sharia law, abandoning much of the secular legislation the country had adopted from its former colonial overlords, the British.

In 1984, the government passed a law that fundamentally changed the day-to-day life of Pakistan's Ahmadis, who were already a marginalized group. Under Ordinance 20, Ahmadis who called themselves Muslims could face three years in jail and an unlimited fine. The law forbade them from using Islamic forms of greeting, referring to their places of worship as mosques or publicly talking about their faith.

Perhaps anticipating the violence that soon followed, the leader of the Ahmadis at the time, Caliph Mirza Tahir Ahmad, moved the faith's headquarters to London. At first, says Rafiq Hayat, president of the U.K. Ahmadi community, it seemed as if they had escaped the extremists. But around 2003, when the community built a new mosque in Morden, London—the largest mosque in Britain—their critics became more vocal. "Anti-Ahmadi Islamic clerics began arriving in larger numbers," Hayat says. "They would preach against us."

Lewis Herrington, a research fellow at Warwick University's Institute of Advanced Study, says extremist clerics first began arriving in the U.K. in the 1990s. Some had fought in Afghanistan against the occupying Soviet forces. After that war, these veteran fighters returned home to find their own governments concerned that they posed a security threat. "Their leaders cracked down incredibly hard on these people, causing many of them to flee to London," Herrington adds. By 2003, when Hayat says he noticed clerics preaching against his community, many of these men had been in the U.K. for several years and had developed a network of supporters.

Ahmadis in Britain also faced hostility from more moderate groups. When the community built its mosque in Morden, the Muslim Council of Britain, the U.K.'s largest Islamic organization, refused to recognize it as a mosque, or the Ahmadis as Muslims.

Things worsened for the Ahmadis in 2010. In Pakistan, the Taliban bombed two Ahmadi mosques, killing 94 people. Hayat says that in some mainstream mosques in the U.K., leaflets described the Ahmadis as infidels and apostates, while some shops and restaurants in London and Birmingham displayed posters that stated they would not serve the group's members.

In 2014, a user calling himself Muhammad Usman posted two videos to the video-sharing site DailyMotion titled "Asad Shah False Prophet 1" and "Asad Shah False Prophet 2." In the films, Shah is seen saying he believes himself to be a prophet. The second video is also on YouTube. In the comments, one viewer wrote two years ago: "He needs to be under [the] supervision of a psychiatrist for his safety and safety of peoples around him." Another concludes with: "Think about your end."

The online comments did not stop Shah, who replied to most of them through one of his three YouTube accounts. He continued to post videos of himself in which he preached love and tolerance. Shah also began writing and printing leaflets centered on the same themes addressed in his videos.

Some people in the Ahmadi community have said that Shah may have been mentally ill, but his family disputes that suggestion. "There is absolutely, categorically no case for claiming that Asad had mental illness," says one family member. "It is essentially slander." (Concerned for her safety, the family member asked to remain anonymous.)

Though Shah's videos drew the attention of people already hostile to Ahmadis—including the person who runs the DailyMotion channel—it is not clear why Ahmed chose to attack him. Shah, after all, had been making his films for years.

A Pakistani man named Mumtaz Qadri might have been the inspiration for Ahmed. On February 29 this year, Qadri was executed for killing a regional governor for whom he worked as a bodyguard. Qadri said he killed the governor because the official opposed Pakistan's blasphemy laws. Qadri's funeral attracted around 100,000 people. Dozens more have visited his grave daily since then, turning it into a pilgrimage site.

Like Qadri, Ahmed has gained a degree of renown in the wake of the shopkeeper's death. One Facebook page is something of a fan site for Ahmed. On it, a user wrote to him: "You just did a super job…. Hats off for your courage [and] love towards Islam [and] Muhammad." Another has posted: "Brilliant job.... Asad liar was mentally sick. He needed treatment."

The anti-Ahmadi messaging has continued to appear offline as well. Soon after Shah's death, worshippers at London's Stockwell Green mosque found leaflets inside the building that said Ahmadis who do not convert to Islam should face death. A trustee for the mosque said the leaflets must have been left there by someone trying to embarrass the mosque.

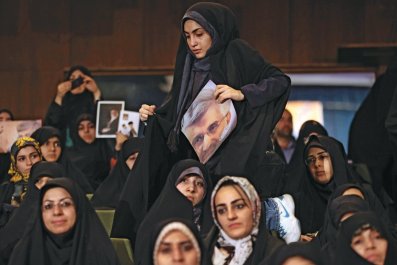

In the face of this hate, the Ahmadi community finds itself pretty much alone in the Muslim community in Britain. The Muslim Council of Britain issued a statement on April 6 saying it does not represent the Ahmadi community. It is, however, investigating the Stockwell Green mosque, which is one of its affiliates, and says it will act swiftly against any other incidents of harassment.

The British police, according to community leaders, do not have the capacity to investigate every anti-Ahmadi leaflet—and since many are in Urdu, the police often cannot understand them.

In Glasgow, soon after Shah's death, a human rights lawyer named Aamer Anwar, who is Muslim, tried to help the local Ahmadi community. On March 31, he arranged an anti-extremism event that was attended by Habib Ur Rehman, the imam of Glasgow Central Mosque, and Ahmed Owusu-Konadu, the press officer for the Scottish Ahmadi community. At the event, the two men publicly shook hands in what Anwar hoped would be a healing gesture of friendship.

Soon after the event, however, Anwar, who has young children, began receiving death threats. "It is extremely upsetting," he says. "It's just a small group of people trying to impose a climate of fear to silence others."

The problem, Anwar says, is that the U.K. isn't monitoring the spread of extremism from Pakistan, in part because militant groups based in Syria and Iraq pose more pressing threats. But, he adds, "what you do not want is a drip, drip of extremism until the point where people think you can take life." The U.K. Home Office, however, rejects Anwar's claim that it is ignoring the threat. In an emailed statement, Home Office spokesman Michael Goldstein says, "The government is committed to tackle all those who espouse hate and violence against others and works tirelessly to protect the British people from all forms of extremism."

Hayat says Shah's killing could have one benefit for the Ahmadis. "We have been speaking to the police for a long time and expressing concerns that there is a deep undercurrent of extremism in the U.K," he says. "Now they understand the hatred that our community faces."

This article originally incorrectly stated that the Muslim Council of Britain (MCB) would not help the Ahmadis monitor harassment. The MCB is investigating one of its affiliates for anti-Ahmadi sentiment and says it will continue to act against harassment.