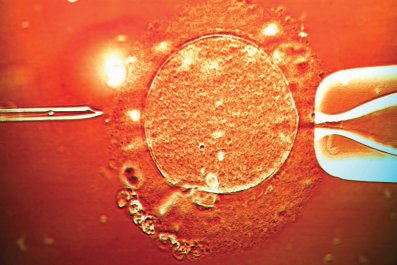

FIRST THE heat. Then the storms. Now the ... pollen? Massive quantities of pollen are floating through the air, causing people to sniff, sneeze, and itch. And it turns out a changing climate could be to blame.

In the Northeast, tree pollen is at the highest level in the 25 years that Leonard Bielory, an allergy and immunology expert at Rutgers University's Center for Environmental Prediction, has been tracking it. He says it's a continuation of a trend he's been seeing for years, and he expects levels to increase by 20 to 30 percent by 2020.

One reason may be heavy rains, like those brought by Hurricane Sandy, that saturate the soil. Rising temperatures are also likely to blame, causing plants like ragweed to bloom earlier in the year—extending the sniffling season for the 10 to 20 percent of Americans allergic to the plant—and also possibly causing some allergenic plants to move farther north, affecting people who didn't know they were allergic. A 2011 study by Bielory found that ragweed pollen season increased by 16 days in Minneapolis from 1995 to 2009, and by 25 days in Winnipeg, Canada. Finally, researchers have found that extra carbon dioxide doesn't just warm the atmosphere—it also nourishes plants, stimulating pollen production and possibly making it more allergenic.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been studying the way changes in CO2 and temperature will affect pollen in order to help local health agencies prepare for our itchy future. "It's an emerging area of interest for health researchers as well as plant biologists," says George Luber, associate director for climate change at the CDC. "We're realizing that the effects of climate change are not limited to extreme weather but to fundamental atmospheric chemistry, which impacts plants independent of temperature." The CDC is studying which plants are most susceptible to increased carbon dioxide so that, for example, they can tell people to start allergy medications sooner, or advise cities not to plant thousands of birch trees, which are allergy time bombs. "We're working with a strong focus on actionable science, producing information that helps decision makers understand the current threat," says Luber.