The publication of Nelson: The Sword of Albion, the second and final volume of John Sugden's monumental life of Horatio Nelson, is a perfect time to reflect on what the admiral's memory still means to Britons today. The book itself takes Lord Nelson from September 1797, when he was at a low ebb having lost his arm in battle and subsisting on opium and half-pay, to his glorious death at the moment of victory at the Battle of Trafalgar eight years later.

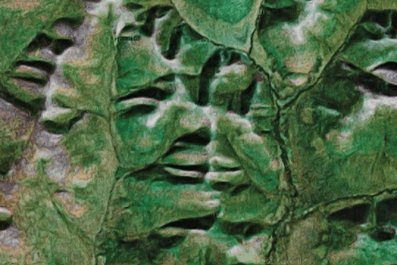

That victory assured Britain's security from Napoleonic France in the short term, and British naval supremacy over the oceans for the next century in the long. Small wonder, therefore, that he is unquestionably one of Britain's greatest heroes, with a reputation that today stands alongside those of Elizabeth I, the Duke of Wellington, and Winston Churchill. The Royal Navy still toasts his "Immortal Memory" every October 21, on the anniversary of his last and greatest victory. This book, though by no means uncritical of Nelson's personal vanity, certainly does nothing to dislodge him from a metaphorical height equal to the actual 169-foot pedestal on which his statue stands in Trafalgar Square in central London.

Born in Burnham Thorpe in Norfolk, England, on September 29, 1758, the fifth surviving son of its rector Edmund Nelson, Horatio Nelson went to sea at only age 12 on the 64-gun warship Raisonnable, under the command of his maternal uncle Capt. Maurice Suckling, and was violently seasick. Nonetheless, Suckling ensured the boy became expert at navigation and sailing, and his training in practical seamanship could not have been better. At just age 14 he was chosen for an Arctic voyage as coxswain of the captain's gig. On his return, he was sent to the East Indies on board the 20-gun Seahorse, but—traveling to every station "from Bengal to Bassorah"—his health completely broke down and he was invalided home.

It was a depressing period for him, but also one that fired the young Nelson with a powerful sense of personal destiny. "I almost wished myself overboard," he later said of this period of his life. "But a sudden glow of patriotism was kindled within me. Well then, I exclaimed, I will be a hero, and confiding in Providence I will brave every danger." By April 1777, Nelson was serving aboard the 32-gun frigate Lowestoft, under the command of his great friend Capt. William Locker, whose military philosophy was simple: "Lay a Frenchman close and you will beat him." It was a lesson that Nelson was to take to heart. He rose by dint of his charm, intelligence, application, and great maritime ability, and wasn't hindered by Suckling's promotion to the comptrollership of the Royal Navy. Nepotism and patronage might be regarded with distaste today, but they helped along the career of Britain's finest naval master and commander, just as they helped along those of Elizabeth I, the Duke of Wellington, and Winston Churchill.

On July 12, 1794, while Nelson was besieging the Corsican town of Calvi, a cannonball struck the ground near where he was standing and splinters flew up, blinding him in his right eye. Three years later he lost his arm to grapeshot. "A left-handed admiral will never again be considered," he lamented. "I am become a burden to my friends and useless to my country."

Events the following year, minutely covered by Sugden in perhaps the best biography of Nelson to emerge in the past two centuries, soon proved him spectacularly wrong.

It was Nelson's inspired guess that Napoleon Bonaparte's fleet, which had slipped past the British blockade of Toulon, France, was making for Egypt, and on the evening of August 1, 1798, he finally caught up with it at anchor in Aboukir Bay at the mouth of the Nile. By sailing round the head of the French line to attack from the landward side, Nelson won one of the most decisive victories in naval history. Only four out of 17 French ships escaped, and Napoleon's army was left utterly stranded in Asia. Nelson was elevated to the peerage and deluged with valuable presents from the tsar of Russia, sultan of Turkey, City of London, East India Company, and so on.

It was when he was recuperating in Naples from a severe wound to the forehead incurred during the battle that he fell in love with Emma Hamilton, the wife of the British ambassador to Naples, Sir William Hamilton. Although it has been presented by romantics as one of the great love affairs of history, she in fact must have been a rather irritating woman, though undeniably sexy. She certainly did nothing to prick Nelson's (understandable) tendency to vanity.

At the end of Britain's short-lived Peace of Amiens with France, Nelson was appointed to command the Royal Navy in the Mediterranean, where he blockaded Toulon, not stepping off his flagship HMS Victory for more than 10 days over the next two years. Yet what a vital two years they were. With a vast army at Boulogne ready to cross the Channel at any moment that the Royal Navy could be decoyed away, Napoleon posed by far the greatest invasion threat to the United Kingdom between the Spanish Armada in 1588 and the Battle of Britain in 1940.

Finally, after two exhausting transatlantic journeys chasing the combined French and Spanish fleets, on October 21, 1805, Nelson managed to close with the enemy and put his mentor Captain Locker's theory to the ultimate test. As Sugden expertly explains, Nelson's battle plan at Trafalgar was to sail through the enemy's line in two columns, cutting it roughly into equal thirds, and then to concentrate the British firepower on the rear two thirds, thus equaling up the numbers between the combined fleets' 33 ships and the British's 27. It was imaginative and daring and was nicknamed by his captains "the Nelson Touch."

The plan was totally successful, although it required great skill and nerve to implement it since the enemy was able to fire broadsides into the British ships for an agonizingly long time before they were able to respond. Nelson led one column in HMS Victory, and just before battle was joined he ordered the hoisting of his famous and stirring signal to the fleet: "England expects that every man will do his duty."

'I almost wished myself overboard,' he said of this depressing period of his life.

The plan went precisely according to Nelson's specifications, but during the battle a sniper from the rigging of the French 74-gun Redoubtable shot him, the musket ball striking his left shoulder and mortally wounding him. "They have done for me at last," he told Victory's Captain Hardy. "My backbone is shot through." Before he died, however, Hardy was able to inform Nelson that 14 enemy vessels had surrendered without the loss of a single British ship. "Thank God I have done my duty," answered Nelson, as he slipped into that immortal glory for which he is still toasted by Britons every year.

It is hard for an Englishman to read this superbly researched and very well-written book without feeling a powerful sense of atavism, yearning, and sorrow about the way it italicizes the contrast between Britain's former naval greatness and her present unprecedented maritime weakness. Today, for the first time in history, the French Navy is actually larger and stronger than the Royal Navy.

Writing to the French ambassador Count Sebastiani in January 1840, the then–British foreign secretary and future prime minister Lord Palmerston, said that "public opinion and ministerial responsibility will never allow an English government, whether it is Whig or Tory, to allow our active fleet to be in a minority with the French Fleet, either in time of Peace or in time of War." He could not have foreseen what happens when defense spending falls into the hands of Treasury ministers during an economic downturn. What a bittersweet experience reading this fine book is for any Briton with a sense of history and maritime pride.