Tyquran Horton, 17, lost one of his uncles before he was born—shot by somebody who wanted his coat in 1990. Another uncle died in 2010: he got into an argument on a street corner and somebody pulled a gun and shot him three times. Then, one afternoon in October 2011, Tyquran's mother, Zurana, was picking up two of her younger kids at Public School 298 in the Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn. Somebody (it's always "somebody") started shooting from a rooftop nearby.

They were wild shots, but there were lots of them. Somewhere on the street near her were some gang members. The guy on the rooftop, from a rival gang, was squeezing off one 9mm round after another trying to hit them. But he hit Zurana Horton instead as she pushed her children against a wall and covered them with her body. Moments later she died, her blood spread across the sidewalk like a Rorschach of urban violence.

So, Tyquran knows something about guns. But he also knows something about the cops looking for them, because Tyquran is a black kid in a high-crime neighborhood and he's been stopped, and questioned, and frisked for no reason that he could see but the way he looked and the time of day.

As we sit in the Bushwick apartment he shares with his grandmother and five younger brothers and sisters, Tyquran talks about wanting to go to college. That's for sure, he says. He dresses for the street and he posts YouTube videos of himself playing a bad-ass comedian. He also studies hard. He wants to be somebody. But between the gangs and the guns, the cops and the stops, that's no easy thing.

"The cops is doing a bit too much to us," he says. If he's coming back home from a party at one in the morning, the cops are "popping out of nowhere" looking for guns. They're in plain clothes. They have unmarked black cars. They're wearing hoodies. "You can't see no face," says Tyquran. "Wouldn't you be scared?" And if you've heard, like he's heard, the stories that cops killed a young man like him, shot him three times in the back, then covered it up, then even if you don't know if it's true, the whole experience is terrifying. Tyquran, whatever his hopes for the future, still lives in a hard world.

On the wall nearby there's a big framed photograph of Zurana Horton with a few words written across it: "In Loving Memory of a Daughter, Sister, Mother & Community Hero." Tyquran glances up at it. "Why should the United States have guns in the first place?" he asks.

SUMMER IS the killing season in American cities. The temperature rises and, yes, tempers do, too. And many young men who might have been in school are out in the streets taunting, hunting, and shooting at each other. Collateral carnage like the slaughter of Tyquran's mother is inevitable, and for many innocents it's inescapable in neighborhoods where young guys spray bullets. In Los Angeles County, with an estimated 450 gangs that have 45,000 members, about half the murders are gang related. Young men get shot again and again, and those who survive show a calm pride when they're wheeled into the trauma units. As a wide-eyed British correspondent reported last week, the doctors call them "frequent fliers." In Chicago, gang and gun violence is endemic, with 12 shootings last weekend and one death. And in New York, although the murder rate is much lower than the other cities, in the rougher parts of town that's no guarantee of immunity. Between Friday and Sunday the first weekend in June, 26 people were shot and seven of them killed.

Over the last few months I've spent time with the New York Police Department and alone in parts of the city where guns are a way of life, but not in the way that pro-gun-rights partisans usually mean. I met kids like Tyquran and cops like Deputy Chief Theresa Shortell, head of the department's fast-growing gangs division. And something that ought to be obvious kept hitting me. The embattled streets of the city and the gunland of the heartland are wildly different places, and the failure to understand that difference, and overcome it, is the great American tragedy of our time.

You've heard a lot of the bitter punditry in the endless debate about firearms in America, which grows more intense whenever there's a massacre at a school or shopping mall, which is often. Sensible legislation is stillborn. And there are occasional acts of apparent madness like the letters laced with deadly poison recently sent to New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg and President Barack Obama. "If you take my guns, you should see what I'm going to do to you," warned the ricin-tainted epistles.

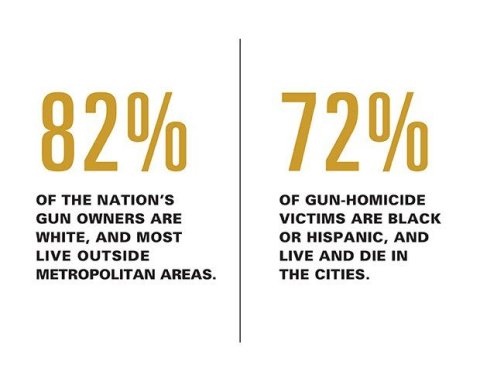

Mostly, the discussions about firearms are framed as a question of constitutional rights for gun owners. But what about the gun owners in Tyquran's world? Are the rights of the 223 people shot to death in New York City last year, or the 435 in Chicago, or the 414 in Los Angeles being protected by the right to bear arms? In big cities across the country, gun control doesn't hurt gun owners, other gun owners do, especially if they are people of color. Recent Pew surveys show that 82 percent of the nation's gun owners are white, and most are outside metropolitan areas, but 72 percent of gun-homicide victims are black or Hispanic, and live—and die—in the cities.

Are the rights of the 223 people shot to death in New York City last year being protected by the right to bear arms?

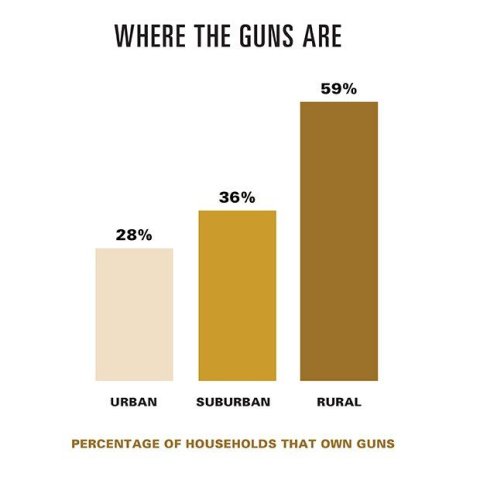

In fact, the seemingly irreconcilable divide in opinion about the nation's 300 million guns is really as much a question of geography and demographics as of politics or ideology. People who live in rural areas and in small towns, or for that matter small cities with small police forces, often feel more secure with a pistol in the house, or in the glove compartment, or on their belt. Sure, they use rifles and shotguns for hunting, skeet shooting, target practice. But many more gun owners say they have firearms for protection than for any other reason, according to a Pew survey earlier this year. In rural America, 59 percent of the households own guns, and the local cops mostly don't mind. In a survey of 15,000 law-enforcement officers throughout the United States, conducted by PoliceOne.com, most of the cops favored less gun control, not more, and more gun carrying, not less.

Over the years I've visited a couple of small towns—Geuda Springs in Kansas and Kennesaw in Georgia—that passed ordinances requiring every household to own a gun. The local politicians wanted to score political points and they got national publicity, but they weren't quite as crazy or cynical as they seemed from afar. In Kansas, especially, the 200 residents of Geuda Springs felt vulnerable when federal funding for local law enforcement got cut off. The sheriff's headquarters was on the other side of the county; crystal-meth traffickers were bringing organized crime to the region. Who could they depend on but Mr. Smith and Mr. Wesson? Kennesaw happily proclaims there have been no murders since it passed its mandatory gun-ownership ordinance in 1982. But only 30,000 people live there, and 30 miles down I-75 in the city of Atlanta, population 450,000, the murder rate is one of the highest in the nation. That's not because the people in Atlanta don't have guns, but because they do. In fact, the cities of the firearm-friendly South have some of the highest murder rates in the country.

Much of the data on the rural-urban divide is fragmented, not least because back in the 1990s Congress punished the Centers for Disease Control for publishing too many statistics the National Rifle Association deemed hostile to gun owners. Legislation introduced by Arkansas Republican Rep. Jay Dickey (no relation) decreed that none of the CDC money "may be used to advocate or promote gun control." There is also some confusion in a lot of the recent statistics that do exist about "gun violence." In the countryside, where guns are so widely available, murder rates are, in fact, much lower than in the cities. But many more people shoot themselves. Among emotional teens, especially, attempted suicides rarely fail when they're squeezing a trigger amid their tears.

What was clear in the early 1990s, when there were about 2,000 murders a year in New York City, half of them committed with guns, was that the homicide rate among kids 15 to 24 years old was five times higher than among the same age group in rural America. And that is the problem that cities are still trying to solve.

"WE CAN'T wait for Washington to act and we have not," New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg told a group of black community leaders a few weeks ago as federal legislation was on its way to failure for the umpteenth time. Together, the politicians and preachers and families of victims met the press in Brooklyn's 81st Precinct, where murders were down from nine last year to just one this year so far. And as the diminutive, pugnacious Bloomberg spoke to skeptical reporters, voices from the people around him sometimes rang out as if at a prayer service. The city has carried out "the most comprehensive attack against illegal guns" in the United States, he said, with "the toughest laws in the country against illegal possession of a loaded gun." Amen.

Bloomberg said he thought other cities could and should learn from his city's example. The billionaire New Yorker, who finances a national coalition called Mayors Against Illegal Guns, spoke with surprise and not a little contempt about the laws in some states designed to prevent municipal efforts to control firearms. These laws against gun regulations out there in Gunland would make the murder and suicide rates go up, said Bloomberg. And he singled out Mississippi: "one of the states with some of the biggest obesity problems, worst education systems, crime, poverty, everything that's wrong is wrong and then you say, 'Why don't they look at other states with things that are getting better?' I don't know."

One reason may be that New York City is not only huge, with a population of 8.5 million; it's also rich enough to support a police force of more than 35,000 sworn officers. Even the Los Angeles Police Department is dwarfed by comparison, with fewer than 10,000 officers, and most towns number their cops by the hundreds, or the dozens, or even in single digits.

It's also a good guess that most folks in rural and small-town Mississippi, while they may loathe Bloomberg, do not much care what's happening to kids and their mothers gunned down in Bedford-Stuyvesant. Nor are most New Yorkers likely to think much about the fears of people living in a poor state with little protection provided by authorities. And it's in the chasm between those two gun worlds, precisely, that laws fail and people die.

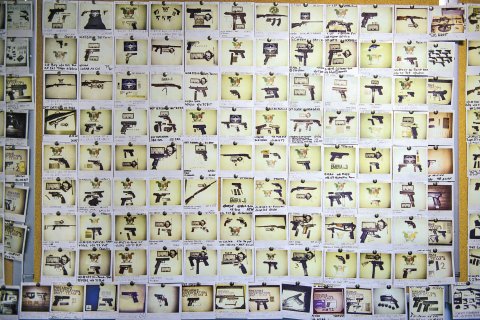

IN A long corridor at the Firearms Investigation Unit's headquarters in East Harlem, Polaroid pictures of hundreds of captured guns fill one bulletin board after another, but most of the photographs are several years old. There wasn't the space to keep pinning them to the wall. In 2012 alone, the gun unit picked up 1,159 firearms in New York City.

"Pennsylvania is a pretty big source state," says Deputy Inspector John Burke, the veteran cop and attorney who heads the NYPD gun unit. Pennsylvania ain't Mississippi, but a lot of it is rural, and by New York standards the Pennsylvania laws are lax. All you need to buy a gun is a local driver's license, and if you don't have one, you can usually find somebody willing to use his or hers to make a few extra bucks. A quick glance on the Internet last month showed, for instance, a Bushmaster AR-15 for sale near Allentown, Pennsylvania, about 80 miles from Manhattan. It's the same kind of gun used in the massacre at Newtown, Connecticut, last year—a weapon designed, says Burke, "for urban warfare." Since it's being sold by a "private party," no background check is needed under existing federal law. The asking price is $1,100. In New York City, according to Burke, you could sell it on the black market for about $1,800. You'd just have to hope you weren't selling it to one of Burke's undercover officers.

In 20 years the number of murders in New York City has plunged (let me reiterate the scale—from 2,000 to just over 400) and partly that's because of a nationwide drop in crime attributable to an aging population, high rates of incarceration, and the end of the crack-cocaine epidemic that plagued the early 1990s. But it's also because the NYPD has moved aggressively and from every possible angle against the sources of illegal guns coming into the city, and also against the people who carry them.

The gun-unit walls show the variety of hardware that turns up on the street, from submachine guns to what used to be called Saturday-night specials; there's a long-barreled pistol that looks like it could have belonged to Wyatt Earp, there are Kalashnikovs like the ones carried by guerrilla fighters around the world. And there are a lot of semi-automatic pistols: mostly 9mm, and some of the new 10mm versions that can penetrate a police officer's body armor.

"Concealed weapons are definitely more of a problem in an urban setting like this," said Burke, leaning forward on his desk, his square face and blue eyes at once terribly sincere and grimly matter of fact. "They are so small now they could be missed by a security guard in an office building, and now you get upstairs with a 15-round magazine and two more in your pocket, you have 45 bullets. You can do some damage."

"Concealed weapons are definitely more of a problem in an urban setting," said Burke. "They are so small now they could be missed by a security guard."

To try to track such deadly weapons, members of the NYPD's Intelligence Division travel to gun shows around the country that they think might be feeding the firearms pipelines. In New York City, the undercover officers from the gun unit make contact with dealers and set up buys. It's one of the most dangerous jobs on the force. Unlike most big drug buys, where guns turn out to be relatively rare, at a gun buy the undercover cop is going to be armed, so is the seller, "and you're dealing with people that $3,000 is something that they would shoot for or kill for," says Burke. Ten years ago, in one infamous case, a deal went bad and two officers died on Staten Island. There's always a good chance in criminal undercover work that you'll set up a buy and the seller will just try to rip you off at gunpoint. When that happened to an undercover cop in 2011, he wound up killing his attacker.

Until recently, much of the city's focus was on the weapons themselves. In the middle of the last decade, the city brought punishing lawsuits against several gun dealers in the South whose merchandise had killed people in the five boroughs. There's an extensive "buyback" program. And the gun unit works closely with the Federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms on a joint task force. When big cases get prosecuted by the feds instead of the state, the penalties are even tougher.

Under Mayor Rudolph Giuliani in the late 1990s the number of murders in New York each year dropped from 2,000 to fewer than 1,000, and many people, including many cops, thought it couldn't be pushed any lower. But for the last 11 years under Bloomberg and Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly, the goal has been to keep driving the homicide rate down to what seemed unimaginable lows. To do that you have to get the guns that are already on the streets, preferably before anyone has a chance to use them.

The emphasis began to shift from the sellers to the would-be shooters. What police critics and most everybody else calls "stop and frisk" the cops call "250s," after the number on the form they're supposed to fill out each time they question somebody for any reason. The information on those sheets, and there are hundreds of thousands a year, can be pretty vague: "furtive movements," is one category, or "high crime area," which isn't always the case.

To push down crime, the NYPD pours rookies into the most troubled parts of the city under a program called "Operation Impact," which began more than a decade ago. If the officers see anyone acting suspiciously, they stop him, question him, and maybe pat him down. But what makes a person look suspicious? In these neighborhoods, most of the population is black or Hispanic, as are most of the victims and most of the criminals. Does that mean the cops are targeting blacks and Hispanics as such? A federal court is examining that question right now, and the issue has become a sensitive one in the early stages of the New York mayoral race.

But what critics see as a question of civil liberties, and young men like Tyquran see as the cops getting out of control, the police see as a vital measure to keep guns off the street. A recent study by Columbia Law Professor Jeffrey Fagan presented in Manhattan federal court showed that just one gun was recovered for every 1,000 people stopped from 2004 to 2012, and there were 4.4 million stops. A failed program? On the contrary, insists Bloomberg, stop and frisk is working. "It would be wonderful if we never catch anybody with a gun," he told the black community leaders around him at the 81st Precinct. "But the reason you're not catching people with guns, we believe, is that they're afraid that they will be caught with one, and so you've altered their behavior. That's what you're trying to do, and we're going to continue to do it."

There were no murmurs of approval on that point from the chorus of community leaders, but there was no condemnation either. "You know, you can stop somebody," said Bishop Gerald Seabrooks of the Rehoboth Cathedral in Brooklyn, a big man with a big voice who towered over the mayor. But "it should be done with 'professionalism, courtesy, and respect,'" he said, quoting back to him the words written on all the NYPD squad cars.

Afterward, over cake and coffee in the precinct captain's office, the bishop buttonholed Police Commissioner Kelly and made the same point again. "I hear you," said Kelly. "I hear you."

THE LIGHTS were low and the video screens on the wall were bright in the command center next to Kelly's office on the 13th floor of One Police Plaza when I went to talk to him one on one about guns and the gangs of New York. "Altered their behavior"? I wanted to know what that meant, and whether stop and frisk was really worth it. Kelly said the tactic was about as old as policing, but there's better record keeping these days. "People want to make it out as a sort of discreet stand-alone program. It's not," he said. There can be any number of factors, but what it comes down to is, "You see suspicious activity, we want you to take action." An example: a couple of men hanging around an ATM late at night, apparently waiting for someone to use it. Is the cop going to ask them what they're doing? Is he going to get a little more aggressive if they try to blow him off?

And the guns? Kelly said many criminals now leave their guns at home, or in hiding places, or sometimes with their girlfriends, unless they have a specific reason to use them. The last thing they want is to be nailed on a weapons charge. There's even a trend toward "community guns" shared by different criminals. All of that reduces the chance of people getting blown away on the spur of the moment for the wrong look or a miscalculated insult.

But the biggest push against guns today, said Kelly, has become the push against gangs: in recent years about a third of the homicides in the five boroughs were related to competition and score settling between rival "crews" in the rougher neighborhoods and housing projects, just the kind of shootings that led to the killing of Zurana Horton.

"It's very much turf based," said Kelly. "It's housing project against housing project, the front against the back." The murderous feuds are, for the most part, not even about money or drugs. These small gangs are not "entrepreneurial," says Kelly. They're all about insults—a lot of which are carried out on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and other social media. The gangs post their taunts on the Web, then brag about what they've done after they've settled a score.

The police, meanwhile, are watching. The cops set up a Facebook site with the face of a pretty young woman, then "friend" one of the members of a given crew and open a channel into the gang's communication network. At first the police had trouble understanding just what was being said. The gangs' argot changed from neighborhood to neighborhood, sometimes even from block to block. Knocking somebody "off a surfboard" could mean shooting a member of the crew called "the Waves." "The Deuce" used to mean 42nd Street in Manhattan, said Kelly. Now it could mean any number of places. The Intelligence Division of the NYPD, among its many projects, has compiled a whole dictionary of crew-speak in the city.

You'd think the gangs would get wise to this and stay off the Web, I said. "No, they don't," says Kelly. "And if they do, it means the violence will go down. So we have accomplished our mission."

Kelly said he believed the focused attack on the 21st-century gangs of New York, Operation Crew Cut, as it's called, was responsible for a 24 percent reduction in the number of shootings in the city, and a 30 percent reduction in the number of murders, at least before the summer killing season began.

But I was left wondering, after we talked, whether there really were, as Bloomberg claimed, lessons for other parts of the country—or, to be more precise, for the other cities in the country. The answer would be yes, perhaps, if they can find the money to pay the cops to do the job. But that's a big if for a job that takes a lot of manpower, technology, and time.

AT 4:30 in the morning on April 3, scores of cops assembled in a precinct muster room for the takedown of 63 members of three crews in East Harlem. Most of the police were in jeans, running shoes, and body armor. Just about the only ones in suits were the NYPD's lawyers, who'd be embedded with each unit on the raids to make sure that everything was done in a way they could defend in court. The bleary-eyed cops ate bagels and drank "Box O' Joe" coffee from Dunkin' Donuts. A cockroach scampered across the floor under one detective's foot. "Wouldn't be a city building without roaches running around," he says. The clock on the wall hadn't been reset for daylight saving time, but the police officers were in sync with each other.

The ranking officer in the room was intense Deputy Chief Shortell, a 29-year veteran of the force and head of the gangs division, which has just been doubled in size to a strength of 300 detectives. Shortell's accent tells you right away that she was Brooklyn born and raised. Her father was a firefighter, she says. Her mother died when she was 3. She worked her way up through the department, including a stint in undercover narcotics. Before the predawn briefing began, she looked over the troops from an array of different divisions in the apartment. "The scruffy ones are probably mine," she said. "These are the people who get a lot of guns off the street."

The case they were looking at that morning grew out of a shooting in 2009, when a member of the crew Air It Out (AIO), based in the Taft Houses project on upper Park Avenue, allegedly shot and killed a member of the Tru Money Gang (TMG), based in the Johnson Houses on Lexington Avenue, setting off a series of retaliations, including two more murders and multiple shootings, and a lot of "shots-fired jobs," as Shortell put it, when people squeezed off a few random rounds that, luckily, hit no one.

Some of the cops in the room carried the bulletproof shields they call bunkers, and the sledgehammers they call rams. They were going to be breaking down doors. "Safety is key," Shortell told them. "It's paramount. All 63 people, all 63 are identified, OK? We know where to find them. If we don't get them today, we'll get them tomorrow, get them a month from now."

At precisely six o'clock in the morning, the cops rolled up to the Johnson Houses and pushed into two of the apartments there to make arrests and search. Virtually all were apprehended or accounted for (several were in jail already) and the operation went off without incident, except that one grandmother had to be handcuffed as her grandson was led away.

In Bushwick a few days later Denise Peace, who lost her daughter Zurana Horton and two of her sons to random gun violence, and who is taking care of Tyquran and several of his younger brothers and sisters, listened impatiently as Tyquran talked about how there were "good cops, bad cops, and worse cops." Peace works with a group called Grandmothers LOV (Love Over Violence). "There are a lot of grandmothers who have lost their children over gun violence," she said. A lot of them are worried they will lose their grandchildren the same way. She didn't have a problem with the cops' stop-and-frisk program, she said. "I think they should check more."