When I was 6 years old, I was in a children's gospel choir. Most of the songs we sang were kids' standards like "Jesus Loves the Little Children" or "He's Got the Whole World in His Hands"—not complicated stuff to understand. But there was one song that we sang every few months that was always a head scratcher for me. This was one of those "walking songs," the ones you march into the sanctuary to, one foot in front of the other with each new line. The words were easy enough, a simple refrain repeated over and over: "We're marching, to Zion, beautiful, beautiful Zion / We're marching upward to Zion, the beautiful city of God."

The first few times we sang this song I just repeated the lines as requested and tried not to trip over my robe. But after a few weeks, the tune really started bothering me. First, I thought to myself, who is this guy "Zion" who lives in God's city? Or, if Zion's a place, how come we never get there? Week after week, month after month, Sunday after Sunday, we were always ... marching. But for some reason, we never, ever arrived.

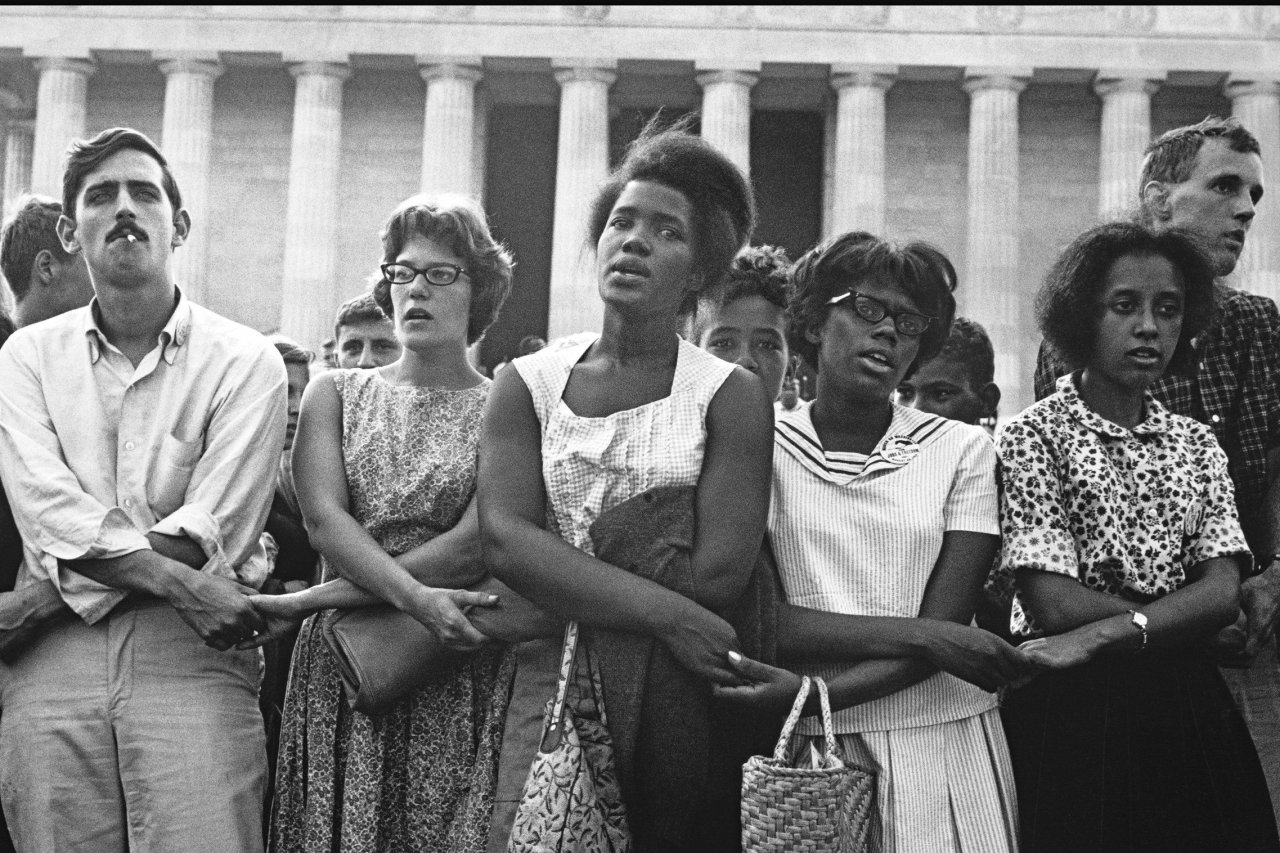

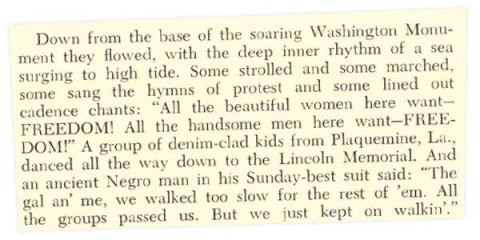

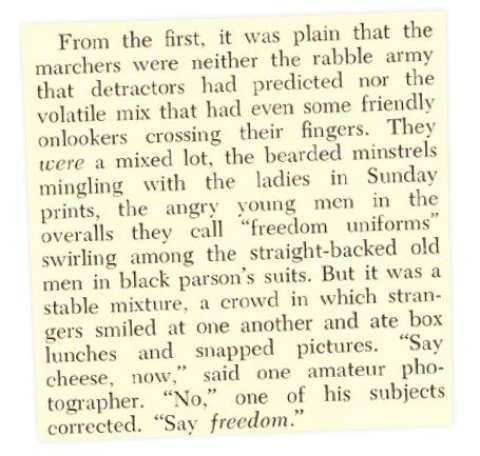

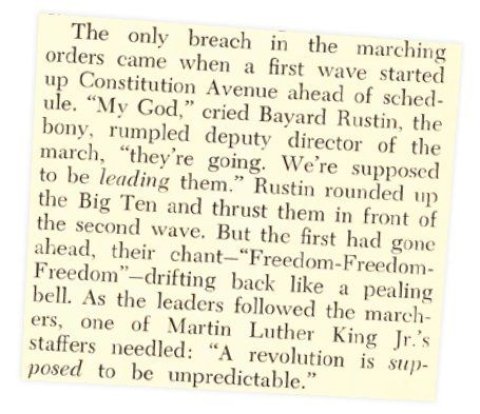

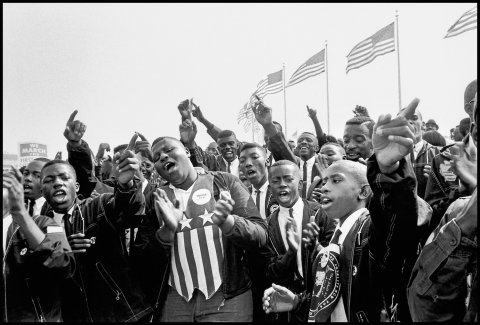

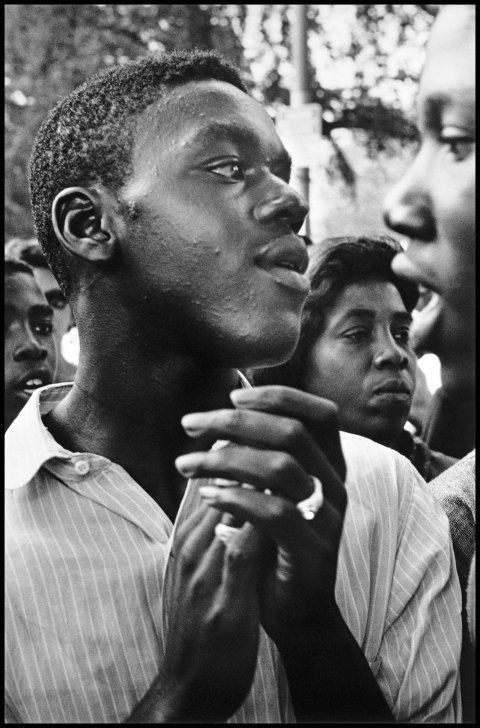

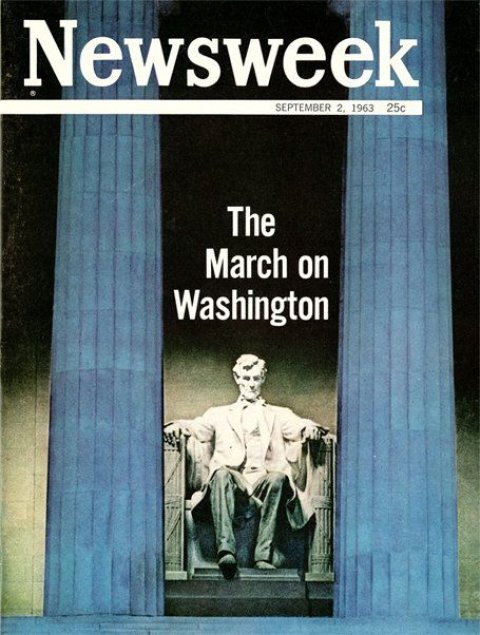

As we approached the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington, the same feeling gnawed at me. I've been involved on the periphery of the plans for the anniversary march, and I will be at the Lincoln Memorial when it takes place next Wednesday. For weeks, I've been reflecting on the extraordinary legacy of the organizers of the original march 50 years ago, people like A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, James Farmer, Roy Wilkins, John Lewis, and, of course, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

But heading into the speeches and ceremonies, worship services and songs, I've also spent a lot of time thinking about Zion. Not the heavenly Zion, but the earthly one—the terminus of our marches, the place where we're supposed to eventually arrive. With this anniversary approaching, I couldn't help but ask myself the same question that stumped me as a child: where is this place we're heading, and when, dear God, will we get there?

My first instinct has always been to answer that open-ended inquiry with an equally squishy response, one that we will hear again and again from politicians, preachers, and activists during the next week: "We've come so far, but we have so much further to go." I've said this line myself, as recently as this past Wednesday, in the pulpit of a Black Baptist church.

It's a phrase that sounds practical, realistic, and even useful. But the problem is: I think it's wrong. And more than just wrong, it is perhaps the primary barrier to real racial progress in this nation.

You see, I believe Dr. King meant what he said: I think he meant for his dreams to actually be realized, and not in some distant future Zion. When he declared that his hope was for "even the state of Mississippi" to be "transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice," I think he meant that Mississippi should get its act together, not hundreds of years from now but right then and there. When he said, "One day right there in Alabama, little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers," the "one day" he was referring to was not the day of his future grandchildren's grandchildren, but the time of his own children and their kids.

When Rustin and Randolph had the original idea for a March on Washington, their goal was not to create a culture of perpetual marches. No, the goal was a focused one: at first, they wanted an executive order banning discrimination in military contracting, which they got. Later, they wanted a Civil Rights Act and a Voting Rights Act, which they also got.

And a day before he died, when Dr. King said, "I may not get there with you, but I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land," he was not posing some abstract, fatalistic vision that he did not intend for our country to realize. No, he was referring to the biblical relationship between Moses and Joshua, and bestowing that legacy on us. We have to remember: Moses took his people almost to their destiny and stopped right short, but Joshua actually walked them in.

Instead of being in a state of perpetual struggle, an endless existential march, I believe there is far more evidence to support the idea that we are right on the verge of Zion. And the only thing that will stop us from getting there is the hopeless belief that we can't.

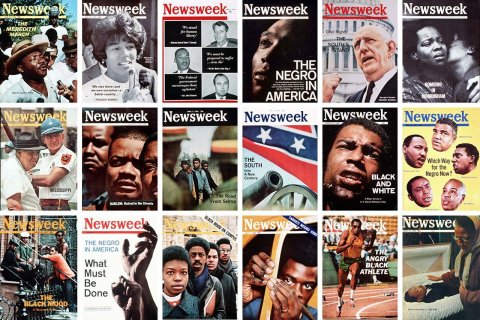

For example, in the early 1970s, following the major accomplishments of the civil-rights movement, 28 percent of black men dropped out of high school. Today that number is around 14 percent. For whites, it's 12 percent. So we don't have "so much further to go"—we have 2 percent to go. Tough, but doable.

Four decades ago, the life expectancy for African-Americans was 66 years old. Today, it is 72. For whites, the number is 77. We don't have many hills left to climb—we have to close the gap by five years of life, when we've already done six. Difficult, but possible.

One major area where our country has actually fallen woefully behind is in the percentage of young black men who are incarcerated, shooting up from 2 percent in the 1970s to 5 percent today, while the percentage of whites in jail grew by less than 1 percent in that same period. Attorney General Eric Holder recently documented some of the reasons for this phenomenon, but he also proposed some real, practical solutions. This is a problem we can actually fix.

The fact is, we don't need to go "much further." We just need to walk two miles from the Lincoln Memorial to Southeast Washington and make sure that the young men and women in high school in Anacostia can fill out their applications for student aid, go to college, and not have Congress cut their Pell Grants. We need to march to North Carolina and ensure that its state legislature doesn't disenfranchise a generation of young people, poor people, and minorities, and to Florida and other states to demand that their legislatures do something about discriminatory laws like "stand your ground." We just need to walk to communities where fathers are not around and help them reconnect to their families, like the Center for Urban Families is doing, and work with employers to provide good-paying jobs and a second chance for ex-offenders, like the folks at Homeboy Industries.

These goals are imminently achievable, and organizations and activists around the country—from the Dream Defenders to Color of Change to the Campaign for Black Male Achievement—are helping us walk the last mile. They are not on some perpetual march to Zion. They're focused on achieving dignity and self-determination for every struggling person in this country, in this generation, right here, right now.

On this 50th anniversary, we should march knowing that we certainly have not yet fulfilled Dr. King's dream. We haven't yet yielded the fruit of our Promised Land and tasted its full measure of milk and honey. But what if instead of seeing this land as thousands of miles off in the distance, we perceived it as being right in front of us, begging us to walk toward it, and enter. Hey, maybe we're even standing on it right now—and all we need to do is bend down and till the soil.