"What is this shit?"

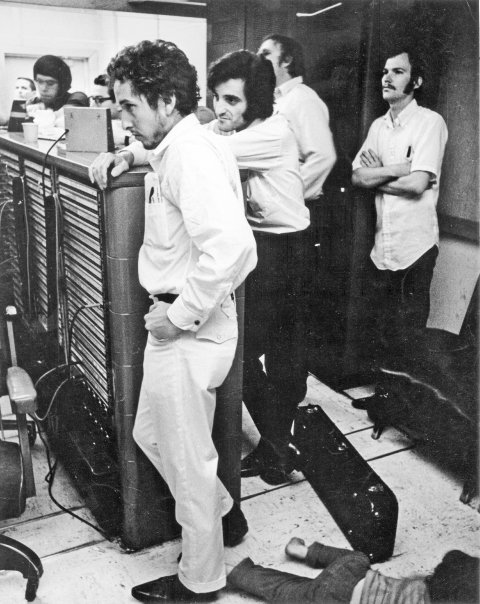

Thus did Greil Marcus kick off his 1970 Rolling Stone review of Bob Dylan's double album Self Portrait. And he wasn't the only one asking that question. The album hit No. 4 on the U.S. charts and No. 1 in England, but many of its millions of buyers were scratching their heads once they heard the music. Expletives abounded.

What could have possibly caused such a ruckus?

The short answer: you had to be there.

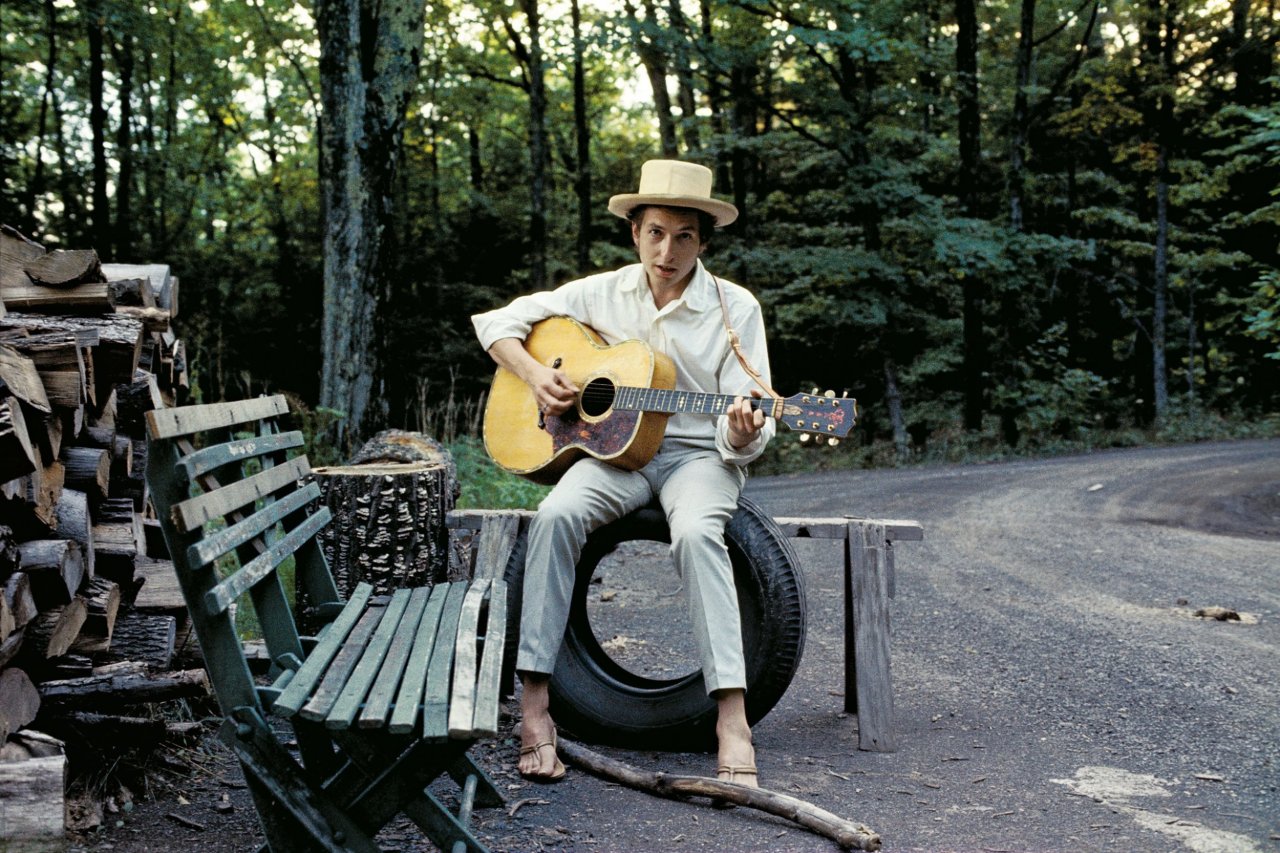

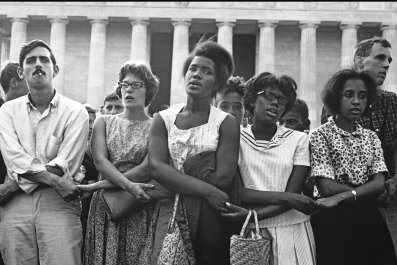

In 1970 Dylan still seemed, to a lot of fans, almost oracular, his Delphic aura ironically gilded by his absence from the public stage following his 1966 motorcycle accident. The press was busy calling him the voice of his generation, a title that I doubt meant much to any of us of that generation (Dylan wryly called himself a "song and dance man"). But clichés aside, he was a fascinating, furiously creative character whom no one took for granted. Popular music has never produced a more romantic figure—a Keats or a Rimbaud with a briar-patch bouffant and an electric guitar—or one more bent on reinventing himself from album to album. Endless motion, endless change; to stand still was to die, and originality was everything. It was a terribly seductive notion there for a while, for him, for a lot of people.

So the majestically electric Blonde on Blonde gave way to the stripped-down acoustic mysteriousness of John Wesley Harding, which was followed by the easygoing country songs of Nashville Skyline. Maybe we were a little taken aback when the man who spat out "Like a Rolling Stone" crooned "Lay Lady Lay," but hey, that was just old Mr. Unpredictable tossing us another puzzle piece. The important thing was that all the songs on that album were his.

Self Portrait was, to mix metaphors, a completely different kettle of wax.

Twenty-four songs on two LPs, and hardly any of them were originals. Instead, we got a weird selection of traditional songs ("Little Sadie," "Alberta"), songs written by other people ("Early Morning Rain," "The Boxer"), songs made famous by other people ("Take a Message to Mary," "Blue Moon"), and songs where Dylan didn't sing at all ("All the Tired Horses," with its female chorus and soaring strings—a string section on a Dylan album!). Only four songs were by Dylan, all live performances, and of those, only one, "The Mighty Quinn," was not previously recorded by the man himself.

At the time, I decided that, given his title, he must be showing us what songs influenced him one way or another ("The Boxer"? Really?). While I liked some of the material—"The Mighty Quinn" exploded out of my crappy record player—I remained nonplussed. I didn't hate it, didn't love it. I just craved an album of Dylan songs sung by Dylan.

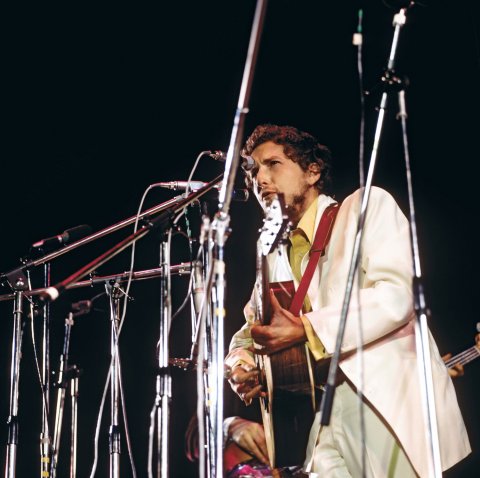

Now, as volume 10 of its official Dylan Bootleg Series, Columbia Records has released Another Self Portrait. This time around, we get two CDs of outtakes, alternate and unreleased tracks, and live recordings. Most of the cuts are from the original Self Portrait, some from Nashville Skyline, and some from New Morning, the successor to Self Portrait. If you spring for the deluxe edition, you also get Self Portrait in its original form and the complete 1969 Isle of Wight concert where Dylan was backed by the Band—and while I'm usually suspicious of deluxe box sets, this is one to grab, just for that ferocious concert, the merits of which can't be oversold.

The big question, of course, is whether this material still makes anyone want to cuss. The answer is, no. Or not likely. But it's complicated.

There's nothing here to make you drastically revise your opinion of the original. The strings and most of the overdubbed instrumentation and backing vocals are gone. The results often sound raw and unfinished, but in this case, that's a plus. On most of the tracks, it's just Dylan and maybe one or two musicians playing songs he loves. There's an intimacy and energy that somehow never found their way into the originals or got drowned out by the too-lavish production.

But the real difference is that the times have changed, and so have we. No one expects anyone's next record to reveal the secrets of the universe anymore. You almost never hear that so-and-so is the voice of a generation. And that's a good thing, as Dylan himself would be the first to tell you.

In Chronicles, his lively, whip-smart autobiography, he tells us that at about the time Self Portrait came out, he was thoroughly fed-up with being the go-to guy for instant wisdom on the counterculture or anything else. "I was sick," he writes, "of the way my lyrics had been extrapolated, their meanings subverted into polemics and that I had been anointed as the Big Bubba of Rebellion, High Priest of Protest, the Czar of Dissent, the Duke of Disobedience, Leader of the Freeloaders, Kaiser of Apostasy, Archbishop of Anarchy, the Big Cheese." (OK, we get it, Bob.) All he wanted, he tells us, was to be left alone to enjoy his kids and his family.

To that end, he did everything he could think of to subvert the notion that he was a spokesman for anyone but himself. One of his stratagems was Self Portrait: "I released one album (a double one) where I just threw everything I could think of at the wall and whatever stuck, released it, and then went back and scooped up everything that didn't stick and released that, too." After that he released New Morning, which did contain original material, some of it good, but nothing on it would change your life. In retrospect, that seems like the point it was trying to make.

The interesting thing to consider, in light of the new release of all that once-controversial material, is that Dylan's efforts to deflect our adoration actually worked. It's not that he never made another great album. Blood on the Tracks, which is one of the finest albums anyone has ever made, was only four years away. And years later, when he again churned out albums of covers (Good as I Been to You, World Gone Wrong), it became clear that this was his way of recharging his creativity while simultaneously tipping his hat to the past. Those records, like his satellite radio show (a showcase for his eerily encyclopedic knowledge of all manner of popular songs), show us Dylan as he sees himself: most at home on a vast musical river fed by the blues, fiddle tunes, jazz, Tin Pan Alley, and Sun Records. In Chronicles, he writes about once meeting Thelonious Monk. Dylan introduced himself by saying that he played folk music. "We all play folk music," Monk replied.

At the time Self Portrait came out, we knew none of that. We just knew we had this odd Dylan album that wasn't really a Dylan album. Most of us certainly weren't ready to understand that "Little Sadie" was every bit as good as "Mr. Tambourine Man," if not better. So we backed away from Bob just a little, and that was good for him and good for us. He could never be just another performer, never lose that ability to raise the hair on the back of your neck. But Self Portrait taught us not to put so much faith in oracles, to be a little more suspicious of the messenger, to see him on a human scale. In other words, it wised us up. In that sense, it was a great album.