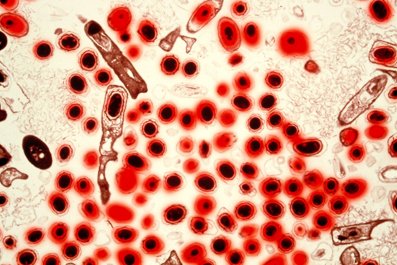

When a meteor plunging toward Earth turned into an enormous fireball over Russia in February, it created a shock wave so powerful that it traveled around the globe twice, even though it never hit the ground. Now the data collected from that not-quite-catastrophic event and studies of the enormous 1908 meteor impact at Tunguska, Siberia, which was hundreds of times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, are helping to sort out the cataclysms of the past. When no crater is identified, scientists have been skeptical about huge meteor and asteroid impacts affecting climate. But as we've seen with the recent events, trace particles of minerals and metals from meteors can indicate a huge event even when there's no known hole in the ground. In one recent study, a team of scientists from Harvard examined samples of ice collected in Greenland that are known to be 13,000 years old. The researchers found a huge spike in the amount of platinum at a moment 12,890 years ago, indicating a very large meteor explosion. That coincides precisely with a sudden cooling in the Earth's atmosphere, and could be linked to the demise of one of America's earliest human populations, known as the Clovis people. NASA, meanwhile, has launched what it calls the Asteroid Initiative seeking ideas for the best way to prevent cataclysms—and extinctions—to come.

Asteroid Initiative Seeks Ideas to Prevent Deadly Impacts