"It doesn't matter if you're discovering a piece of music or a film—it's very similar," says Fabien Riggall, founder and creative director of an organization that prides itself on restoring a sense of drama and mystery to familiar forms of entertainment. Riggall's first project, Secret Cinema, uses actors and performers to re-create the world of a film as a setting for its screening, and he is now attempting to do the same in music. His new initiative, Secret Music, launched in July with a run of 17 performances by English singer Laura Marling in an abandoned building in East London.

As usual, few details were revealed in advance. Those attending Secret Cinema's screenings are not even told the film they will be seeing. Tickets to Secret Music were sold on the strength of Marling's name, but we were told nothing about the world we would be entering; we were given only an address in East London, a dress code (vintage black tie), and a few cryptic references to a hotel. We were told to bring flowers, a book, maps, and a photograph of an old lover, and when we arrived at the abandoned building that had been turned into the "Grand Eagle Hotel," to be greeted by name at the gates, we found the rooms littered with items left by other guests.

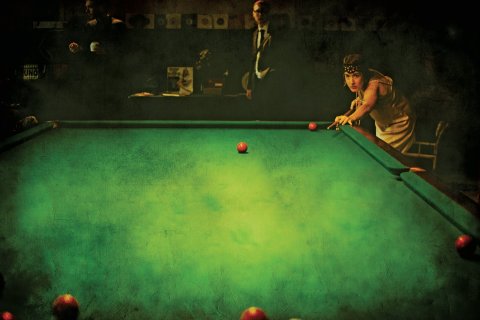

Actors drew us in to their imagined intrigues: I talked to a woman who said she had come to the hotel with her husband and her lover, and my wife was presented with a copy of a book containing a handwritten note that began, "I saw you arriving this evening and thought you looked so beautiful I just had to give you something." A scratchy print of Renoir's La Bête Humaine was being screened in one room. Guests played billiards in another. The fashionable London restaurant Moro ran the so-called Secret Restaurant, which included a vegan option designed by Marling.

As the next phase of the evening began, a busker sang in one of the flower-strewn rooms, and a dancer in a red dress performed a masque in the hall downstairs. Marling performed in an adjoining hall lined with white drapes and hung with chandeliers. Red velvet curtains framed the stage. The woman in the red dress was carried through the crowd, and a man playing the role of the hotel's owner, Thomas Undine (named after "Undine," the ninth song on Marling's latest album), came on stage and asked us to introduce ourselves to our neighbors. The characteristically English pause before everyone complied was one of his favorite parts of the evening, Riggall told me when we met a week after Marling's run of sellout concerts had finished, because it fulfilled his ambition of allowing people "to connect in a different space."

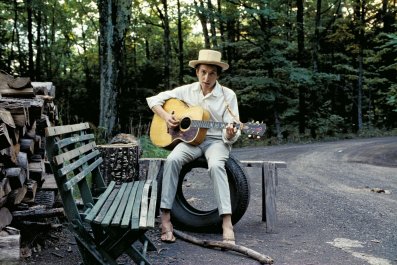

When the chatter subsided, Marling took Undine's place: she was dressed in white, and she played with her head thrown back, often gazing at the ceiling. She did not address the audience for the first four or five songs of her performance, and when she did, it was only to acknowledge their appearance: "It's nice to see you all looking so smartly dressed," she said. She was a rapt, abstract presence; I was not surprised to discover that Riggall thought of her as a ghost, based loosely on Ophelia, Hamlet's lover, and imagined her drifting through the building, handing out dead flowers, and singing. Riggall said he saw her as someone "from another time, another place," which was why he had staged the performance in the 1920s, though he conceded that it was possible to interpret Marling's cryptic lyrics in other ways. Not surprisingly, he liked the fact that her songs are hard to decipher. "They're riddles," he said. "They're secrets."

Riggall began his career making short films, and in 2003 he set up a network called Future Shorts, which has expanded to 150 cities in 55 countries. In 2007 he put on the first Secret Cinema event, a "staged screening" of Paranoid Park, Gus Van Sant's film about a skater who kills a security guard. Since then Secret Cinema has screened The Battle of Algiers in tunnels beneath the Old Vic theater in south London, filled the Alexandra Palace with camels for Lawrence of Arabia, and re-created the dystopian vision of Terry Gilliam's Brazil in a 13-floor office block in Croydon, South London. In the aftermath of the London riots, in 2011, Secret Cinema staged simultaneous screenings of Mathieu Kassovitz's La Haine in Tottenham and Kabul. It has re-created the worlds of such classic films as Casablanca, The Third Man, and Grease and staged new films as well: its elaborate setting of Prometheus, Ridley Scott's prequel to Alien, was presented during the film's opening weekend.

Each year their shows attract an audience of 100,000 to 120,000 people—many of whom are prepared to spend £50 on a ticket for a film whose name they don't know. And Riggall is still attempting to expand the concept of the "secret event," which he describes as his "mad dream" of creating worlds around music, film, fashion, art, and music. "The ability to be creative, to let go, to indulge a sense of play—that has been lost," Riggall says. "It doesn't happen in traditional cinema, and it doesn't happen at a traditional gig."

Other recent initiatives include Secret Swimming (an attempt to break the world record for the largest simultaneous swim ever recorded), Secret Hotel (people were invited to stay in "cells" modeled on the state penitentiary from The Shawshank Redemption), and Secret Books (collaborations with publishers to mock up the world of a newly published book). Next year he hopes to stage a Secret Festival, which will feature many different artists performing in worlds styled around them in the way the Grand Eagle Hotel was styled around Marling.

In the meantime, Secret Cinema is expanding internationally: in 2010 it turned a New York gallery into a mock-up of London in the swinging '60s for a screening of Antonioni's Blow-Up and staged Alien in Berlin. It has plans for more events in New York and two other cities in the U.S., though for the time being, Riggall is not divulging details. A post on Secret Cinema's New York Facebook page sums up the approach: "The job is to seek mystery, evoke mystery, plant a garden in which strange plants grow and mysteries bloom. The need for mystery is greater than the need for an answer." New York may have to wait for the next Secret Cinema event, but when it comes, Riggall believes the city will accept the invitation to be more than a passive spectator: "Above all, audiences are looking to be part of something. They want to be able to contribute and get closer to the artists they love. I don't think the current framework gives them that opportunity."