After I pop the poop in my mouth, it occurs to me that maybe my safari guide is lying. Maybe this scrub hare's pellet doesn't contain vitamin A or E or B like he says. Maybe it's just ... poop. But he has just thrown back one of the grassy bites too, after explaining that hares dine on their own waste to absorb the vitamins produced during their food's wild ride through the colon. "They're good for the eyes, too," he says. I swallow. Unsurprisingly, it tastes like dried grass and dirt. The locavore inside me is strangely pleased.

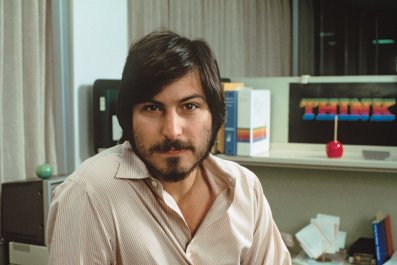

At the moment, there's no confirming these facts (and who knows what horrors appear after Googling "can I eat rabbit droppings?") because it's mid-June and we're on a walking safari in the South Luangwa National Park in Zambia. Besides, I've grown used to these kinds of stories told by my weeklong safari guide, Manda Chisanga, a native Zambian with 16 years of guiding experience, and I trust him implicitly. Manda is an expert at matter-of-fact storytelling tinged with humor, and knitting together fact with what sounds like myth. From the constellations in the sky to the roots of a tree, he knows something about everything.

My excursion is care of the Bushcamp Company, which operates the Mfuwe Lodge and six luxury camps, all secluded and beautifully appointed, in the nearly 3,500-square-mile park. The guides, including Manda, specialize in night drives and long walks in the morning or afternoon—really, as long as the sun is up. This isn't the crowded caravan-of-Jeeps adventure that I had imagined; outside of our group of four, we never come across another tourist. One of the three camps we spend the night in is called Chindeni, after the Chindeni Hills surrounding the park, and, yes, there's a story behind those, too:

"One day, long ago, a woman attempted to climb these hills. Burdened with many goods, she was grateful when a man offered his help. On the other side of the mountain, she told the man she could not pay him. That's fine, he said, you can sleep with me instead. And that's how the Chindeni Hills got their name …"

It's useful, then, to know Chindeni means "fornication" in Nyanja, one of the native languages of Zambia. A favorite of honeymooners, the private chalets of Chindeni camp are tented, raised, and have hammocks overlooking an oxbow lagoon with two resident hippos. It's also where, in typical safari fashion, we wake each day with the sunrise, have breakfast (corn porridge, French-pressed coffee, thick bread toasted over glowing coals, local peanut butter), and clamber into a Land Rover for a morning drive.

Often, when it's safe, our group will get out with Manda and walk around the bush, which requires a trained scout carrying a rifle to take the lead. The fact that our scout is six feet tall is comforting, but I only truly believe I won't be maimed when he tells us that his first name is Priest.

When Manda finds something of interest, practically every three feet or so, he stops and speaks with a quiet authority. "The park can be dramatic," he says. "Always be ready for surprises." Many are underfoot. One lesson strangely left untold in The Lion King (and its two egregious sequels) is the disparities in mammal dung. Lion scat appears white because of calcium from all the bones they've consumed; buffalo waste looks as you'd expect, like giant, deeply furrowed raisins; an elephant's dark pellets likely mean he ate earth to cure an upset stomach.

One afternoon, we encounter a herd of elephants, or "ellies," as Manda nicknames them. "It's tough to be an elephant," he says. "They move about the bush all day eating." Sounds familiar, I think, remembering our week of 6 a.m. breakfasts, 11 a.m. brunches, 4 p.m. tea times, and 8 p.m. dinners. The smaller ellies dutifully follow the herd. "Matriarch stops, everyone stops. Matriarch moves, everyone moves," Manda says. "The matriarch is everything in the elephant world."

More facts fly fast and furiously: the African wild dog (which we never find) is more closely related to the jackal than the dog; the gorgeous seven-colored lilac-breasted roller is the most photographed bird in Africa; hippos can hold their breath for eight minutes, and in order to mate, the males, those showoffs, possess what Manda calls "extended urinary instrumentation"—a nifty euphemism coined on safari by a creative physician and one that I tuck away for future cocktail conversation.

Not all is quiet and serene on the South Luangwa front, though. There are other stories, too, full of strife and injury, like the one where a Cape buffalo attacked two men near the airport, putting them in the hospital for two weeks. Sometimes animals are their own worst enemies. Wart hogs, which we often see darting in the middle of the road, can keep running and running, Manda says, but because they lack sweat glands, occasionally they'll convulse and die. This fact makes me grateful for sweat glands for the first time.

The guides and camp managers often talk about animals with the caveat "We shouldn't anthropomorphize." Yet even Manda laughs when we come across a group of male buffalo, calling them bachelors, old and alone, without a female in sight.

We also can't help but reverse-anthropomorphize ourselves with the question, "If you could be any animal, which one would you be?" Manda has his answer at the ready: "A martial eagle," he says. "Because in my dreams I'm always flying." When asked to assign animals to everyone else in the group, he chuckles and wisely declines. No one wants to be told she's a hippo.

Throughout the week, animals are plentiful: ambling giraffes; thieving baboons; napping lionesses; the elusive honey badger, so rare Manda hadn't seen one in three years; and uncountable impala, so prevalent the running joke is that the furry white "M" around their tails stands for McDonald's, because "there's one on every corner."

But there is more dung to be touched. During another afternoon walk, Manda rolls around in his hands an incredibly hard cylinder that he explains was once the home of a scarab beetle. The beetles roll all manner of dung into a ball (apparently by following the Milky Way, the only insects to do so), then burrow a deep hole to lay their eggs. Once hatched, the larvae stay at home for a year with their all-you-can-eat dung buffet before flying away. How amazing, I think, all the crap they have to crawl through to get to the next stage of their lives. They're like the millennials of the insect world.

I've learned hundreds of facts about flora, fauna, and mating rituals, but have yet to witness the main event. It's no secret everyone goes on safari with a little blood lust. You want to witness beast versus beast, then draw mosquito nets around your bed at night, and leave with the ultimate story. Which explains why the night we come across a leopard stalking a herd of impala, I nearly shriek with anticipation. Crouched low in the tall grass, the leopard inches closer as the oblivious impala trot away, their eyes shining like Maglites. Either she senses our anticipation or doesn't want to put on a show, and, after 45 minutes, the leopard gives up. "She's young, inexperienced," Manda says. "You can tell from her pink nose. But she'll learn."

After a drive and dinner, we sit around the campfire with Manda and the conversation winds its way to family. His great-grandmother would gather him and neighborhood children around a similar fire, Manda says, where he'd have to fill up her giant metal mug with tea leaves in exchange for "amazing, fantastic stories" he can no longer remember. But he does recall entertaining his peers in grade school with a story about a monkey who pretended to be human by wearing his tail as a belt. The kids loved it. "I wish I could still tell stories like that. I can't anymore," he says. All I can think of is how many mugs of tea I owe him after this week.

A few days later, we say goodbye at the Mfuwe Airport, an hour's drive from the main lodge. I'll eventually fly from Zambia's capital, Lusaka, to South Africa, and embark on one of the longest flights in the world back home—17 1/2 hours from Johannesburg to New York via South African Airways—which provides time for a bit of Manda's advice to ring in my head. His warning about spotting dangerous animals in the bush by looking forward, never backward, comes bumper-sticker ready: "The most important thing is not about where you're coming from, but where you're going."

Equally as important, I should add, is whom you might meet—and what turds you might eat—along the way.