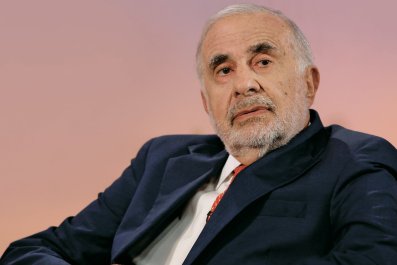

New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg said it was unfair and "a nightmare," and Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly called it "offensive," "disturbing," and "recklessly untrue." But by August 12, when federal Judge Shira A. Scheindlin rendered her historic 195-page verdict in Floyd v. City of New York, ruling "unconstitutional" the way in which the city's cops disproportionately subject blacks and Latinos to the department's crimefighting "stop and frisk" tactics, she had long been at war with the powers that be.

Back in May, in a highly unusual move, Bloomberg's operatives publicly questioned the 67-year-old Scheindlin's judicial integrity as she was beginning the three-month trial in which David Floyd, a 33-year-old African-American medical student who was stopped and frisked twice, claimed his rights had been violated by racially profiling police. The mayor's staff leaked to the media an in-house study indicating that since President Clinton put Scheindlin on the bench in 1994 at the behest of Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, 60 percent of her written "search and seizure" rulings had gone against law-enforcement authorities—something they suggested showed bias.

Lifetime-appointed federal judges seldom play to the court of public opinion, and the billionaire mayor obviously didn't bargain for Scheindlin's full-throated response. Noting that the correct figure was more like 5 percent when her oral decisions from the bench were taken into account, she called the leaked study a "below-the-belt attack" on judicial independence and, in a blistering interview with the Associated Press, added that the mayoral staff's action was "quite disgraceful ... Judges can't really easily defend themselves ... To attack the judge personally is completely inappropriate and intimidates judges, or it is intended to intimidate judges, or it has an effect on other judges, and that worries me."

Not only does Judge Scheindlin believe she can fight city hall, she plainly relishes the battle.

"She's not an establishment judge, and she has never gone along lockstep with the establishment," says prominent defense lawyer Gerald Shargel, who has known Scheindlin since she was an assistant U.S. attorney in the Eastern District of New York three decades ago. "She's very smart, and she doesn't suffer fools gladly. And if she sees something that needs fixing, she'll take every judicial step to fix it." Scheindlin, who is famously hardworking and demanding of her clerks (forbidding them from eating lunch away from their desks) and runs a strict courtroom (although she once allowed criminal defendant John "Junior" Gotti to croon "Happy Birthday" to her on the day she turned 60), didn't respond to Newsweek's request for comment.

Her ruling, which the city plans to appeal, explicitly allows police to continue employing "stop and frisk," but it empowers a federal monitor, Manhattan attorney Peter Zimroth, to ensure that minorities aren't wrongfully targeted. She is also requiring the NYPD to establish a pilot program in which cops in specific precincts must wear cameras to record their interactions with citizens. The cameras would provide "a contemporaneous, objective record of stop-and-frisks," Scheindlin wrote in her ruling, that could "either confirm or refute the belief of some minorities that they may have been stopped simply as a result of their race."