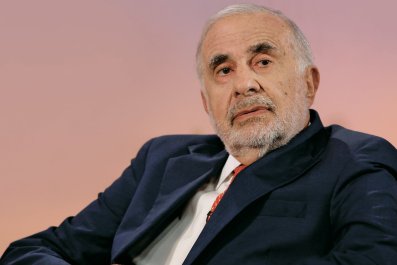

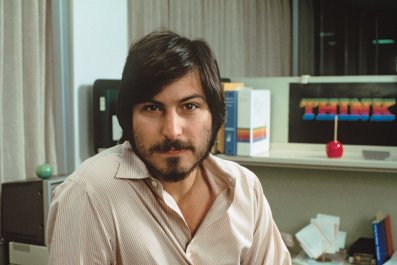

A few months ago Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos was on a roll. Two out of three Colombians approved of the Santos government—a rock-star standing by the bruising political standards of the Andes. The country's $370 billion economy was soaring, overtaking Argentina as the fifth largest in Latin America. Foreign investors lined up as prospectors found oil, gas, and coal practically everywhere they dug. Crime, once a national scourge, was plunging. The only thing missing was peace. And so, late last year, the savvy 62-year-old economist turned president declared, "The stars are aligned," and set out to secure a peace deal that would end the insurgency by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), which has lasted more than half a century.

But, after 12 tough rounds of negotiations in Havana, even the significantly weakened FARC may be proving too hard for Santos to handle. Certainly, hope of a peace deal by November looks increasingly unlikely. So far, the government and the rebels have come to agreement on just one item on a five-point agenda: land reform and rural redevelopment. And as Santos himself has said: "Nothing is agreed until everything is agreed."

As negotiations have dragged on, the national mood has dragged down. The most recent polls show that two thirds of the country now disapproves of the peace effort or the way the government is handling it. Overall support for the Santos administration has tumbled from 70 percent two years ago to barely 50 percent. More troubling still for Santos, 60 percent of those surveyed said they don't want to see him reelected next year. "You can't negotiate a peace plan without considerable political support, and that is slipping," says Michael Shifter, the president of the Inter-American Dialogue, a policy think tank. "That is bad news for Santos."

Colombians have been through this before. Starting in the 1980s, five presidents tried and failed to broker a peace with the legendary guerrilla group, which eventually took over a third of the country, threatening to turn it into a failed state. During the last go-around, in 1999, the FARC commander declined to show up at the negotiating table and left President Andrés Pastrana talking to an empty chair.

In the fall, when Santos announced yet another peace plan, most Colombians were stunned—and many were furious. Perhaps his harshest critic was Álvaro Uribe, his predecessor and onetime mentor, who had waged an all-out war against the FARC while in office.

Ironically, it was Uribe's unrelenting pursuit of the FARC that paved the way for the current peace plan, allowing Santos to wave an olive branch from an unprecedented position of strength. With dimming prospects for peace and a looming election, the irony may be lost on the Colombians—and on Santos himself.