The pain and the irregular bleeding told Nanotte Pierre there was something wrong. But none of the doctors she visited over a decade could tell her what it was. An infection, they thought, but none of their expensive therapies put an end to the problem. Instead, it worsened.

In 2013, Pierre's younger sister, who made her living selling sweets on the street, was working outside a Haitian gynecology clinic called Klinik Manitane. Nearby, a river of plastic foam and plastic bottles choked a drainage ditch, and the sun scorched the road until it swirled with dust. But the clinic was pleasant, and the women who'd come to see a health care professional waited on benches shaded by a salvaged UNICEF tent.

One day, the clinic was passing out appointment cards to the women outside and handed one to Pierre's little sister. She thought maybe Pierre should go in her place. Maybe the people there could finally do something about her problem.

It was a brutally hot August day when Pierre, 42, went to the clinic, and she felt seized with pain. There were women in front of her in line, but she wasn't leaving without seeing a doctor. When it was her turn, Pierre undressed and reclined on the exam table. A midwife sat down before her with a speculum, a light and a liquid smelling strongly of vinegar. The midwife was so surprised by what she saw that she immediately called over a doctor, who brought in another doctor, an American woman who entered the room by greeting Pierre in French.

When she inspected Pierre, her face became serious. Pierre did the only thing she could do. She lay there and prayed. "I have a God that won't let me down," she thought as the American doctor scraped out a piece of her with a long, scissor-like tool. The diseased flesh went to a lab, and for a month Pierre waited in pain. She worked at a local market, where she sells odds and ends, and she made arrangements for her sister-in-law to take care of her 14-year-old daughter when she was dead.

When the results came back, Pierre was told she had invasive cervical cancer.

If Pierre were American, she probably never would have gotten cervical cancer at all. In the developed world, it's largely a historical disease. But Pierre lives in Haiti, where by some estimates the rate of cervical cancer is the highest in the world. Surgery is prohibitively expensive, chemotherapy drugs are limited and there isn't a radiation center in the country. One typical treatment option is group prayer.

We Cured Cancer

Death by cervical cancer is torture. In A Women's Disease, historian Ilana Löwy's book on the illness, she describes the final weeks in the life of Ada Lovelace, daughter of the poet Lord Byron, who died in 1852. "Maddened by pain that could no longer be controlled entirely by opiates, she could not be held in bed and threw herself against the furniture or on the floor." A century later, Argentine first lady Eva Péron, known as Evita, was in such agony at the end of her life because of her cervical cancer that doctors gave her a lobotomy in hopes it would quiet her pain.

There is good news, however. When people ask, "Why haven't we cured cancer?", part of the answer is that, for some forms of it, we kind of have. We've nearly solved cervical cancer. In the beginning of the 20th century, it killed more American women than any other kind of cancer. Now it is among the least lethal forms of the disease.

That's thanks to medical innovations developed over nearly two centuries. Doctors in the 1800s, with brash (and mostly fatal) surgical interventions and primitive speculums, studied "cancers of the womb" extensively. Even in those early days, doctors hypothesized that if cervical cancer could be detected sooner, it could be stopped. Once, by accident, a doctor who removed a cervical lesion for biopsy discovered that the removal had prevented the lesion from becoming cancerous. Through such observations, cancer of the cervix became the paradigm for how all cancers might one day be treated. As Löwy put it to me, the thinking was that "this is the way we should win the war on cancer. We should find it early, and we could solve it early."

Visible symptoms, however, never present themselves early enough. The pain Pierre experienced for years is not typical, and her doctors still aren't sure it was connected to her cancer. Rather, irregular bleeding is usually the first indication that something is wrong, but this seldom occurs until the cancer has already spread to the uterus or beyond. By then, it's usually too late.

Around the turn of the century, doctors began to argue that screening apparently healthy women would save lives. In the 1920s, Georgios Papanikolaou, a Greek-born doctor working at Cornell University, developed a test that became known as the Pap smear, and in the 1940s the American Cancer Society promoted its regular use.

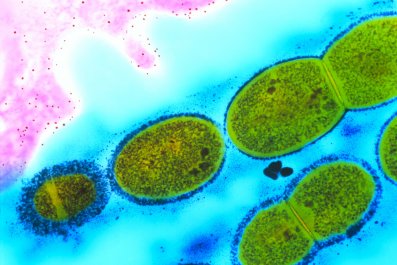

In the 1990s, researchers made another breakthrough. They discovered that virtually every case of cervical cancer has a single cause: the sexually transmitted human papillomavirus (HPV). Since the 2000s, HPV vaccines and new screening techniques that test for the presence of high-risk strains of the virus have opened up a remarkable prospect: Cervical cancer could one day vanish.

A Poor Woman's Disease

By some counts, Haiti has the highest incidence of cervical cancer in the world. It kills nearly as many women there as all other cancers combined. Meanwhile, in North America it's responsible for less than 3 percent of female cancer deaths.

Worldwide, more than half a million women developed cervical cancer in 2012, and more than half of them died. Eighty-five percent of those cases occurred in the developing world. Even in the U.S, the disease is more prevalent among blacks, Hispanics and whites in Appalachia—groups with the least economic means. Cervical cancer is a disease of poverty.

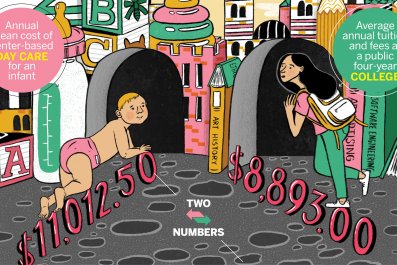

In large part, this is because the latest prevention tools aren't available or affordable in poor countries. Per capita income in Haiti is $810 per year, according to the World Bank, and many Haitians cannot pay for Pap smears. Even if they could, there aren't enough laboratories or personnel to analyze them. According to U.S. doctors I talked to who work in Haiti, there are fewer than 10 pathologists in the entire country.

Sometimes tests are inconclusive, requiring follow-up. But many Haitian women can't take time from work to travel long distances for a screening. And if the results are positive, then what? Except for the wealthy elite, no one has money for treatment. There is no health insurance in Haiti.

One solution advanced by some public health experts is VIA, a low-cost alternative that stands for "visual inspection with acetic acid." Acetic acid is the main ingredient of vinegar. When it is painted onto the cervix, precancerous lesions turn white. Almost anyone can be trained to do it.

That's why that American woman, Dr. Rachel Masch, the executive director of Basic Health International, was at the Port-au-Prince clinic Pierre visited that day in August 2013. She was training midwives on the VIA procedure. Basic Health, working with the California-based aid organization Direct Relief and the Haitian nonprofit St. Luke Foundation, has screened thousands of women in Haiti's capital city and has likely saved several dozen lives through prevention.

Whenever they notice a dangerous-looking spot, they freeze it with a long metal prod super-chilled with nitrous oxide, killing the cells before they can become cancer. Sometimes there are side effects, including bleeding and mild cramping. In rare cases, women will experience a decrease in cervical mucus that can inhibit sperm. "VIA is not the most perfect screening," said Paulina Ospina, senior program manager with Direct Relief. "There's a higher degree of false positives. So you do have overtreatment." But proponents of "screen-and-treat" say it beats the alternative: undiagnosed cancer.

In September 2013, Pierre received a phone call from a Haitian doctor who worked on her biopsy. She needed Pierre to come back to Klinik Manitane but wouldn't give her any straight answers over the phone. The most the doctor would say was, "You've had a cancer attack."

When Pierre arrived, she met with Masch, who said, "I'm going to be frank. You have cancer." Pierre cried. Masch let her sob for a little while, then explained what treatment would be like. There would be surgery. She would have to travel far from home to be bombarded with radiation and chemotherapy. "What do you think you want to do?" Masch asked.

"Well, I don't have any more money," Pierre said. She'd spent it all on other doctors and other hospitals that couldn't get to the bottom of her illness. When Masch assured Pierre she wouldn't have to pay anything, Pierre consented to undergo treatment.

Jesus Will Cure Her

Early the next year, Pierre was on the phone with her doctors again. It was important, they said, to remove Pierre's cervix, uterus, ovaries, part of her vagina and possibly several pelvic lymph nodes as quickly as possible. "When can you come in for surgery?" the doctor asked.

"Well, I have this money that I owe at the bank," Pierre said. She borrows money to buy food, accessories or various household items, which she sells at the market, then pays the money back after a month or two. She needed to keep working and pay the debt; she figured by April she could move into the black.

"You can't wait that long," the doctor said. "You need to have the surgery now." Pierre relented, and they scheduled the operation for February 2014.

For the next few months, Pierre felt shattered and overwhelmed. The pain still nagged at her, and her bank loan loomed. Her young brother couldn't bear to see her like this. In the past, when he couldn't find work or needed a roof, Pierre was there. She was the strong one who found the money, who held the family together.

Meanwhile, Masch called on two other doctors to volunteer to help her with Pierre's surgery. St. Damien Pediatric Hospital, a sister hospital to St. Luke, offered up a surgical suite. After some last-minute reluctance from Pierre's family—"You're not going to cure her!" one member told the hospital director, "Jesus is going to cure her!"—Pierre went on the table.

Masch, Ospina and others cast about the U.S., El Salvador, Cuba and the Dominican Republic for a facility that could provide chemo and radiation therapy. Direct Relief, which received more than $14 million that year, had set aside some money for cases like Pierre's. But the organization's worldwide mission and strict program budgets limited the resources it could devote to a single cancer patient—it was supposed to screen thousands of women, not cure one. Pierre would require travel, lodging and weeks of therapy. She didn't even have a passport.

"Everybody went into this knowing that if we weren't able to find the treatment, then she would very likely die," Ospina said.

But through colleagues at the nonprofit Partners in Health, which would also pay for part of her care, they found a hospital on the other side of the island, in the Dominican Republic. Pierre secured a passport and a visa, and one day in August, she boarded a bus for Santiago in the Dominican Republic. The center there tried to make her feel comfortable, connecting her with the local Haitian community. But mostly she spent those four months feeling weak, sick and lonely. "I felt like I was exiled," she said.

A $10,000 Patient

When I met Pierre in late May, she had just learned she was cancer-free.

Direct Relief spent about $10,000 treating Pierre. That figure did not include donated care and the hundreds of volunteer hours and personal expenses of 50 people in at least five organizations who worked on her case. That year, 1,500 Haitians died of the same disease.

In developed countries like the U.S., cervical cancer screening is incorporated into the health infrastructure. When a woman sees her gynecologist, it's simple to add a Pap test or colposcopy exam (in which a doctor uses a magnifier to inspect the cervix). But in Haiti and other developing countries, primary care is almost nonexistent—which means screening is more or less absent too. One of the biggest problems is that most practitioners and facilities in Haiti are in the capital. Reaching women in rural areas would require establishing programs in clinics nationwide.

Representatives from the Ministry of Health did not respond to Newsweek'smultiple attempts to reach them, but several people told me about government-driven plans in the works for regional screening clinics to use HPV screening or Pap smears. "They want to see a national effort," said Dr. David Walmer, who has been working on cervical cancer in Haiti since 1993 and is collaborating with the Haitian government through his organization, Family Health Ministries.

The barriers to adequate health care, though, are significant here. Dr. Josette Bijou, a public health expert and former presidential candidate, cites corruption, the centralization of resources in Port-au-Prince and, most important, the "lack of financial resources." Haiti is a beneficiary of billions of dollars in foreign aid, of course, but so much of it is squandered through inefficiency and corruption. In addition, there is the difficulty of organizing efforts. I spoke with several organizations and individuals who are trying to solve this problem, and very few of them are working together to build a comprehensive plan.

The day I met Pierre at Klinik Manitane, her husband wandered over to me. There was no interpreter, but we exchanged a few words in broken French. I told him his wife is very lucky, but he disagreed. He said, "She's favored by God."

This article is one in a series from Newsweek's 2015 Cancer issue, exploring challenges and innovations in cancer treatment and research. The complete issue is available online and at newsstands.