Somewhere on the grimy streets of an industrial city in northeastern China walks one of the world's most dangerous men. Stocky and fleshy-faced, with a mole on his upper lip, Li Fangwei keeps a low profile and operates under several aliases. In another time and place, he might have boasted about his criminal empire like a colorful cocaine kingpin, machine-gunning rivals and showering the locals with soccer stadiums. But Li's business requires more discretion: He sells advanced missile and nuclear technology and materials. To Iran.

Indicted in New York last year for Iran sanctions-busting and money laundering, Li—known in the West as Karl Lee—operates out of Dalian, the Yellow Sea shipping center formerly known as Port Arthur. Once talkative, he no longer answers his phone. Employees at a half-dozen of his companies contacted by Newsweek said they'd never heard of him.

But Lee is well known to U.S. officials and arms control specialists. To them, he's second only to A.Q. Khan, the notorious Pakistani scientist who gave Iran, North Korea and Libya road maps to the bomb. "A.Q. Khan is in a class by himself," says Robert Einhorn, a top former nonproliferation official in the Clinton and Obama administrations. "But if Khan occupies places 1, 2, 3 and 4, then Karl Lee is clearly No. 5.... He's done a lot of damage."

Other analysts agree. "Karl Lee's importance as a supplier to Iran's missile program can't be overstated," says Nick Gillard, an analyst with Project Alpha at King's College London, which has closely tracked Lee's transactions. "If you were to take apart an Iranian missile, there's a good chance you'd find at least one component inside that's passed through Lee's hands." In recent years, Gillard says, Lee has graduated from selling technology and advanced metals made elsewhere to becoming a producer of "highly sensitive missile guidance components such as fiber-optic gyroscopes, making the leap from middleman to high-tech manufacturer."

Which makes him a wild card in the sweeping arms deal with Iran that extends the ban on selling ballistic missiles and parts to Iran for another eight years. If China can't—or won't—control him, Congress will never vote to lift sanctions on Iran, predicts Senator Mark Kirk of Illinois, a leading Republican hawk. "While this administration may temporarily waive some Iran sanctions laws to advance flawed negotiations, Congress will never vote to permanently repeal these laws until the Iranian regime's nuclear ballistic missile and terror threats end once and for all," Kirk tells Newsweek.

But there's the rub. Starting with the Clinton administration over a decade ago, China's response to behind-the-scenes protests from the U.S. over Lee's activities has ranged from "never heard of him" to "go fish," according to present and former officials. And that remains unchanged, judging by Beijing's response to an inquiry about Lee from Newsweek in June. In a prepared statement, the spokesman for China's Washington embassy insisted Beijing takes proliferation of weapons of mass destruction "seriously," but declined to comment on Lee.

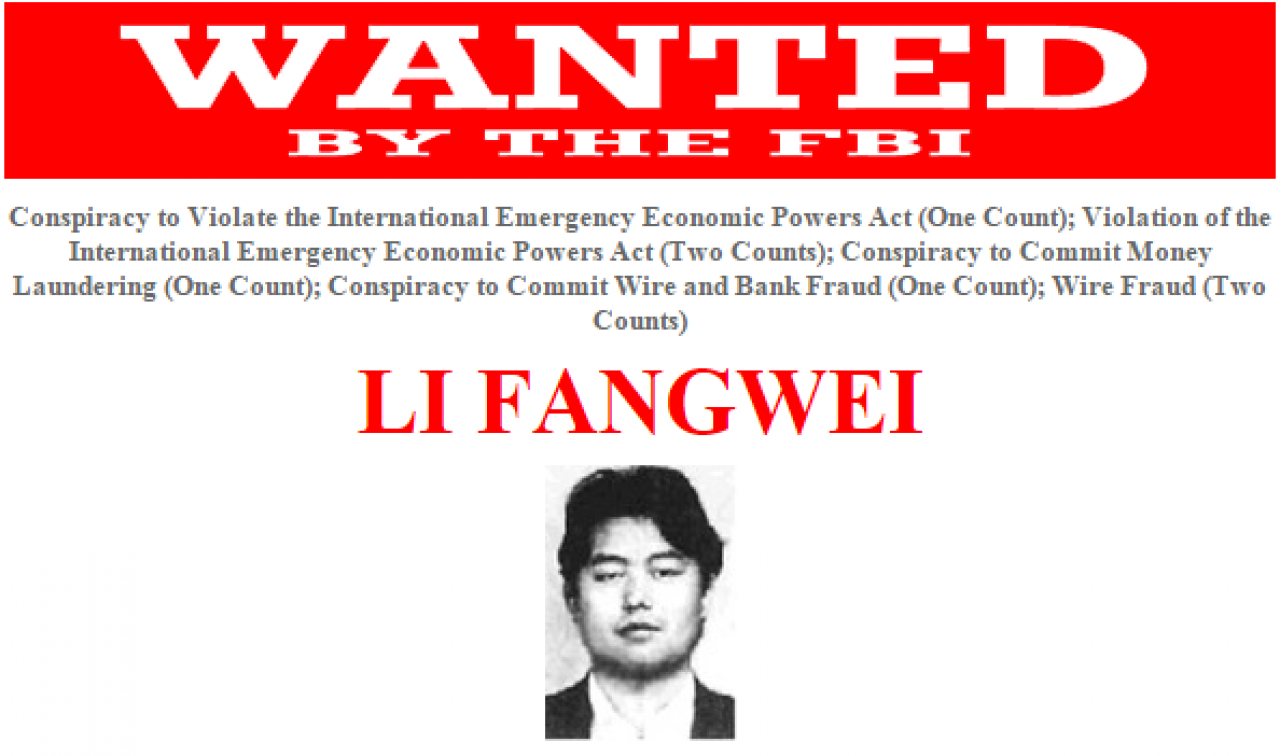

The Obama administration began ratcheting up pressure on Lee last year, designating more of his companies for sanctions, hanging a $5 million reward on his head and issuing an Interpol "red notice" for his arrest if he travels outside China. The FBI also seized $7 million of his assets and issued a "wanted" poster with a blurry picture of the smirking, tousle-haired 42-year-old. As fast as they hit Lee's operations, however, he closes them and pops up under new names and accounts.

Many officials say it's time to castigate China publicly for protecting Lee and demand that it turn him over for prosecution. "It's way past time for naming and shaming," says Einhorn, who discussed Lee personally with Chinese officials during the Clinton administration.

Presented with the opportunity to do just that this month, however, the Obama administration demurred. The State Department official responsible for nonproliferation declined an interview request. The Justice Department refused to say whether the U.S. has formally asked China to turn over Lee. And a senior administration official, speaking strictly on a not for attribution basis, offered only a boilerplate response on how the U.S. and China "continue to deepen" their "cooperation on nonproliferation and counterproliferation issues." To be sure, he says, "the United States continues to consider Karl Lee a priority proliferation threat."

That was it. The administration was reluctant, of course, to say anything that might complicate the Iran nuclear talks at the last moment. Now that an accord has been reached, however, Lee's dealings give Washington hawks another chance to hammer the White House. Proof of China's intractability, they say, can be seen in how little U.S. law enforcement knows about Lee's family, education, party connections and lifestyle—a reflection of how they've been stonewalled by their Chinese counterparts. By tracking his commercial transactions, however, they think they've identified companies registered under the names of his father, Li Guijian, and two brothers, Li Fangchung and Li Fangdong.

But where did Lee get his technical and business expertise? Where did he learn to speak English? They don't know. Is he living large, like Pablo Escobar? They don't think so, although they say he's fond of luxury cars and nice suits. That's it. Beyond his business dealings, he's a cypher. "We have worked on him a long time," says Matthew Godsey, a Chinese-speaking senior research associate at the Wisconsin Project, chuckling. "It's hard to pin down who he is personally."

Investigators know Lee was born in Heilongjiang, a hardscrabble province bordering on Manchuria, in 1972, when China was being turned upside down by the ultra-leftist Cultural Revolution. By the time he was in high school, however, the country was well on the road to exuberant, state-guided capitalism, aided by its nascent ties with the United States. But how Lee made the leap from the rustic far northeast to the booming port city of Dalian to world-class notoriety as Khan's heir in the black market nuclear-arms business remains a mystery—at least in Washington. One U.S. government investigator says Lee had a grandfather who was a "legendary colonel in the People's Liberation Army" during the Korean War, which probably helped.

By the early 2000s, Lee was "connected," as gangsters say. A classified 2008 State Department cable obtained by WikiLeaks described him as "a former government official who has been using his government connections to conduct business and possibly protect himself from Beijing's enforcement actions."

"If you're trying to think through why the Chinese don't [stop] with this guy," says a congressional staffer who spoke freely about Lee only on condition of anonymity, "there are two explanations and possibly more. One, they like what he's doing—and you have to ask why. Or two, he's got to be paying people off."

Or both. Indeed, lots of government and party officials probably have their beaks in Lee's businesses, the staffer says. "That's the Chinese way of doing business."

But many Lee-watchers think he's Beijing's man in Tehran, a very useful cutout for arms sales, a "private businessman" they can pretend is freelancing. With the prospect of sanctions being lifted in the wake of the nuclear arms accord, so this thinking goes, that could put China at the head of the line in the Iran arms bazaar.

Meanwhile, most experts laugh when asked about the prospect of China ever handing over Lee for prosecution. He has made himself virtually irreplaceable to both Beijing and Tehran, if only because of "the amount of time that Iran has invested with him," a federal investigator says. "The degree of tradecraft that he has used makes him a seasoned veteran," he adds, referring to Lee's skill in working through dozens of fronts under multiple aliases. "It takes time to develop somebody else like him, and clearly he's able to act freely within China. So you've got someone who can move freely, who has been trained for over a decade and uses really good tradecraft. That's kind of hard to replace."

He is, in short, much like Nicolas Cage's character in Lord of War, a Russian-born American by the name of Yuri Orlov who deals arms to a score of bad guys on behalf of clients like the CIA, which needs to keep its hands in the savage conflicts hidden. In the movie, a zealous Interpol agent (Ethan Hawke) finally tracks down Orlov and throws him in a cell. The agent thinks it's the end for Orlov, but the arms dealer assures him he's wrong.

"Let me tell you what's going to happen," Orlov says, sitting in handcuffs. "Soon there will be a knock on that door, and you will be called outside. There will be a man in the hall who outranks you.... First, he will compliment you on the fine job you have done...that you are to receive a commendation, a promotion. And then he's going to tell you I am to be released.

"The reason I will be released is the same reason that you think I'm going to be convicted: I do rub shoulders with some of the most vile, sadistic men calling themselves leaders today," Orlov continues. "But [for] the president of United States, who ships more merchandise in a day than I do in a year, sometimes it's embarrassing to have his fingerprints on the guns. Sometimes he needs a freelancer like me to supply forces he can't be seen supplying."

Somewhere in China, there's probably a policeman who thinks world peace would be served—and his career enhanced—by arresting Karl Lee. But that would be foolish. As Orlov puts it, "You call me evil, but unfortunately for you, I am a necessary evil." To Beijing, of course, Lee is hardly evil, but he's necessary.