The city never agrees with the country. If you embrace one, you spurn the other. The divide harks back to the rift between Alexander Hamilton, the New Yorker who saw cities as the future of America, and Thomas Jefferson, the gentleman farmer of Monticello, who compared cities to sores that vitiate the body.

The American antipathy to cities informs the assignation of state capitals, only 17 of which are in the largest city in their respective state. In New York, this divide is especially pronounced. New York City accounts for about 43 percent of the state's population and is the acknowledged world capital of finance, media, culture and Cronuts. That makes for a perennially testy relationship between the global metropolis and Albany, the state capital. New York City can hardly repaint a crosswalk without Albany, whose governor and Legislature must answer not only to Brooklyn and the Bronx but to Butternuts (pop. 1,786) and Almond (pop. 458). In the end, Jefferson's vision prevails, the large city sapped of strength by competing country interests.

"New York is the nation's largest city, yet it has to go on bended knee to a scruffy, dysfunctional state government, based in what it looks upon as a hick town," says New York Daily News state affairs columnist Bill Hammond. Similar conflicts sprout across the land, perhaps most notably in the dispute over the minimum wage, which has risen in cities like Seattle and San Francisco thanks to local legislators intrepid enough to act on their own. Such efforts, though, have met with blowback. "As city after city has voted to give low-wage workers a raise in recent years, state after state has passed laws limiting local governments' power to do so," reports the Pew Charitable Trusts.

There is only so much the city can do in a system that grants enormous power to the state capital. The perfect example of that limit is Albany, where the city's aspirations are trumped on everything from the subways, run by the state's Metropolitan Transportation Authority, to rent control, which falls under the auspices of the Division of Housing and Community Renewal.

The political knife fight now taking place in New York is especially odd because both the governor, Andrew Cuomo, and the mayor, Bill de Blasio, are city guys who identify, at least nominally, with the white ethnics of New York City's outer boroughs. Both are Democrats who worked together in the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development under President Bill Clinton. They both have national ambitions, but it is their exceedingly public disagreement that has lately garnered attention.

De Blasio asked Albany for extended mayoral control of the city's public schools and funds for an affordable housing program. Legislators from both parties rebuffed him, giving de Blasio only one year of school control and an eviscerated housing plan. "Mr. de Blasio's camp was dismayed" upon learning of what Albany had to offer, said The New York Times, which added that "the frustration appeared to be reaching near-existential levels" in City Hall.

These were not the first indignities suffered by the mayor at the capital's hands. De Blasio's signature campaign program in his 2013 mayoral bid was universal pre-kindergarten, which he intended to fund with a tax on the wealthy. But that would require approval from Albany, where Republican legislators have considerable strength and where the governor is aligned with Democrats on social issues but contemptuous of their long-standing fealty to public sector unions. Cuomo gave de Blasio $300 million for the pre-K program but without increasing taxes, thus claiming some ownership over the mayor's signature program. De Blasio also picked a fight against charter schools, loathed by his teachers union supporters. On Albany's "Lobby Day" in 2014, de Blasio attended a teachers union rally, but Cuomo upstaged him by showing up at a huge demonstration of charter school students bused up from New York. De Blasio lost that one too.

By this past spring, de Blasio was accustomed to losing, but having an anonymous source in the governor's office—almost certainly the governor himself—call him "bumbling and incompetent" was a fresh insult on top of legislative injury. Bloodied and on the ropes, de Blasio hit back. In an interview at the end of June, he unloaded on Cuomo, accusing him of having a "lack of leadership" and harboring a "vendetta" against those who cross him. "I think he believes deeply in the transactional model," de Blasio sneered. Cuomo took this with the glee of a seasoned politician. "The mayor was obviously frustrated he didn't get everything he wanted from the legislative session. Welcome to Albany," Cuomo said with condescension.

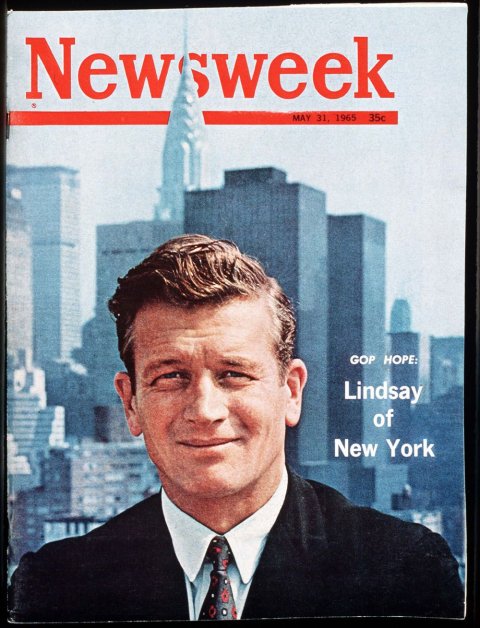

Those who know history know that the feud between city and state will not end well, fun as it may be to watch. In 1966, John Lindsay strode into City Hall in lower Manhattan as the Republican answer to John F. Kennedy. "GOP Hope," said the cover of Newsweek in the spring of 1965, showing a dashing Lindsay in front of the city's skyline, a coolly confident smile on his delicate patrician lips, hair sculpted to perfection. At his inauguration, Lindsay promised urban renewal and racial uplift, so unabashedly messianic he makes the Barack Obama of the hope-and-change days look like a milquetoast actuary. New York "is a city in which there will be new light in tired eyes," Lindsay vowed.

Eight years later, Lindsay's eyes were glazed over by an unending procession of defeats: debilitating and deeply embarrassing strikes by transit and sanitation workers, a teachers strike stemming from a nasty fight between Jewish educators and black activists in Ocean Hill-Brownsville, a blizzard that kept Queens buried long after Manhattan was cleaned, a "riot" by blue-collar workers furious at Lindsay's opposition to the Vietnam War, a "blue flu" strike by the police department. "Fun City," as his New York was once famously branded, had become broken and broke by the time Lindsay left office in 1973.

The man who stood in Lindsay's path was then-Governor Nelson Rockefeller. Much as Cuomo and de Blasio share certain superficial characteristics, so did Lindsay and Rocky, both Ivy League–educated uptowners flirting with the left wing of the Republican Party (Lindsay: Upper West Side, Yale; Rockefeller: Upper East Side, Dartmouth). Lindsay was grand in vision and contemptuous of those who did not share it. Rockefeller was the shrewd backroom dealer, eager to show he was more than just his name but rarely shy when it came to using the immense influence that name suggested.

During the 1968 garbage strike, Lindsay asked Rockefeller to call in the National Guard. The governor retorted, "You can't move garbage with bayonets." In 1971, as the city's finances continued to deteriorate, he rebuked Lindsay publicly in a lengthy letter to The New York Times, imperiously lecturing his downstate rival on fiscal probity: "I know how difficult it must be for you to make adjustments similar to those I had to make."

Lindsay, for his part, called Rockefeller a "tool of the White House" of Richard Nixon and branded his Fifth Avenue apartment Berchtesgaden, a favorite Hitler retreat. In a famous slogan from the 1969 campaign, Lindsay called being mayor of New York "the second-toughest job in America," suggesting a low opinion of Albany. Nor was this merely electioneering bluster. "I've told Nelson that in power, complexity, and responsibility, my job dwarfs even his and that he ought to keep that in mind," Lindsay had told journalist Nat Hentoff the year before.

"The mayor thought the governor autocratic; the governor thought the mayor incompetent," says Richard Norton Smith, author of the recent On His Own Terms: A Life of Nelson Rockefeller. In the end, the two men wore each other down, neither achieving the national prominence he sought. Rockefeller was appointed vice president, but as he once said, he "never wanted to be the vice president of anything." Lindsay's own run for the presidency in 1972 was a disaster; his try at the Senate, in 1980, didn't go much better. By then, he was widely seen as the man whose profligate spending had brought about the 1975 financial crisis. A return to law practice proved as inauspicious as a return to politics; despite the impression that Lindsay was to the manner born, his finances were such that, in 1996, Rudy Giuliani gave Lindsay a city sinecure so that the man once branded the Republican answer to JFK could simply have health care.

Joseph Viteritti, a professor of public policy at Hunter College and the editor of Summer in the City: John Lindsay, New York, and the American Dream, notes that Lindsay saw himself as a "national spokesman for cities," while de Blasio is a "voice for economic justice" who wants to be heard across the nation, eagerly using City Hall as his bully pulpit. Earlier this year, de Blasio touted a national progressive agenda; his trips to Iowa and Washington, D.C., have some pundits wondering whether he is already tired of City Hall.

Yet neither city nor state triumphs when its top dogs go for each other's throats. "By the time Rockefeller and Lindsay were finished torturing each other, the city was on the verge of bankruptcy, and the state's finances were as brittle as a maple leaf in November," writes Terry Golway of Capital New York.

Financial ruin on the scale of '75 is not likely to result from the Cuomo–de Blasio fight, but stories of legislative dysfunction are still injurious. The sooner this stops, the better for all, except perhaps the tabloids. Seeking to put an end to the squabble, the prominent Republican Alfonse D'Amato, a former U.S. senator, invited the pugilists to a "pasta summit" at Rao's, the impossible-to-get-a-table Italian legend in East Harlem. It was a charming gesture of goodwill. Both the mayor and the governor declined.

About the writer

Alexander Nazaryan is a senior writer at Newsweek covering national affairs.