On June 16, 2006, Iraqi insurgents attacked a military checkpoint near Yusufiyah, Iraq, killing Specialist David J. Babineau and capturing Pfc. Kristian Menchaca and Pfc. Thomas L. Tucker. Immediately, the U.S. launched a massive search involving 8,000 U.S. and Iraqi troops, which lasted until the soldiers' remains were found three days later, the sort of effort we have come to expect when U.S. soldiers go missing. Though more than a dozen Americans were MIA during the Iraq War, only Major Troy Gilbert's remains have yet to be fully recovered, and Afghanistan currently has one prisoner of war, Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl. That's a staggeringly low count by historical standards. Vietnam has 1,643 service members still unaccounted for, Korea has 7,903. But by far the greatest number of missing service members, dwarfing other conflicts, comes from World War II. Of the 83,000 soldiers listed as missing in the past century, 73,000 disappeared in World War II. And their remains are still being recovered.

Wil S. Hylton's Vanished: The Sixty-Year Search for the Missing Men of World War II, tells the story of one such recovery effort. On September 1, 1944, a B-24 Liberator bomber piloted by 2nd Lt. Jack Arnett was struck by antiaircraft fire and crashed near the South Pacific island of Palau. Eyewitnesses saw two or three parachutes emerge from the falling plane. None of the men were heard from again, and their families spent the next six decades wondering what happened.

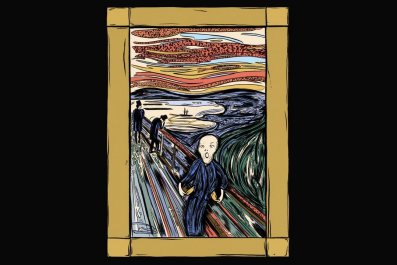

Though the lost service members of World War II may seem ancient history, Hylton does an admirable job explaining how the peculiar horror inflicted on the conflict's MIA families can continue to the present day. One of the few researchers to study the issue, Pauline Boss, terms it "ambiguous loss." Grief and uncertainty make for a potent mix. "What distinguished the missing soldier from other combat losses," Hylton writes, "was that the family was deprived not only of a son, but of a clear explanation for his loss. Without knowing where the man died, or how, they faced a story with no ending, and their inconsolable grief had as much to do with narrative as with death."

It's a grief that passes down through generations. Hylton quotes the clinical handbook for multigenerational trauma, in which an entry on MIA families appears alongside entries on the Holocaust, slavery, and nuclear annihilation: "Unlike the Holocaust, mothers of MIA children were not suddenly uprooted from their homes and deprived of their possessions, countries, and cultures. They did not lose parents, siblings, and husbands to programmed incineration. They were not subjected to incarceration, underfed, and abused, as were Holocaust victims.... On the other hand, most children of Holocaust survivors have not waited for over a quarter of a century in a state of ambiguous grieving, wondering whether their parent is dead or alive, as children of MIAs have done."

Tommy Doyle, the son of one of the airmen from the Arnett bomber, was one such child. There were rumors in Doyle's family, whispers he'd heard his whole life that maybe his father Jimmie was still alive, that "he'd survived in the crash. He'd come back from the war. He was living in California with a new wife and two daughters." Instead of the horrible certainties given to most Gold Star families, Doyle and his mother lived with both grief and doubt. "The slightest mention of this dad," Hylton writes, "would bring [Doyle] to tears." And he was hardly alone. Diane Goulding, the wife of another airman on that plane, lived with the belief her husband must be alive. She sustained herself by writing to the families of other crew members. "I thought I'd just offer my sympathies and I know how you must feel," she wrote in one early letter. "Everything is so uncertain. One doesn't know what to think." That feeling continued for decades.

In the early 1990s, however, a biotech researched named Pat Scannon developed an interest in amateur wreck-diving. He was part of a team that discovered the wreck of the first Japanese ship sunk by George H. W. Bush, and his interests rapidly turned to the downed aircraft of the Pacific Campaign. After he'd discovered several bomber wrecks, he gained the attention of the MIA community. "That was the biggest surprise," Scannon said. "I wasn't sure how many families even cared anymore, but when you talk with them, the first thing you find out is that the later generations care even more - it's like there's an empty chair at the dinner table all their lives." Meeting with the families lent a sense of urgency to Scannon's hobby. By the new millennium, that hobby had become an organization, BentProp (short for bent propeller), staffed by volunteers and boasting its own logo and military-style challenge coins. The military's personnel recovery unit, the Central Identification Laboratory, began working with Scannon. Over the years and through several missions to Palau and countless hours spent studying old military records and bomb damage assessment photographs, BentProp slowly gathered the clues to locate the Arnett bomber. At this point the military deployed a team of deep sea divers, bomb defusers, fishermen, Air Force historians, forensic scientists, a physician specialized in super-oxygenated fields, and an anthropologist specialized in underwater recovery in an attempt to finally allow these families a degree of closure.

Vanished is not only a story of war and loss but also a gripping and moving tale of America's relationship with the fallen soldier. The recovery of an underwater B-24 costs the American taxpayer $1 million. Hylton doesn't give a final tally for the cost of the Arnett mission, but aside from all the volunteer work, it involved two deployments of highly specialized personnel, the construction of special cage to shore up the plane, and several years of work from the Central Identification Laboratory. Few nations have the ability to underwrite such efforts, but they're an important part of the bargain between citizen and soldier. When someone joins the military, they entrust themselves to the care of the U.S. body politic. U.S. citizens elect the leaders who order soldiers to war, and they pay for the war with their tax dollars, so they damn sure better bring those soldiers home - dead or alive. Since the U.S. has mostly been able to honor this bargain, it's easy to forget what an historical anomaly it is. To give some perspective, Hylton references Drew Gilpin Faust's account of Civil War dead "thrown by the hundreds into burial trenches; soldiers stripped of every identifying object before being abandoned on the field; bloated corpses hurried into hastily dug graves."

As our experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan testify, those days are long gone - at least for Americans. Though the wars produced countless missing persons - the Red Cross claims that 20,000 bodies were left at the Medico-Legal Institute in Baghdad between 2006 and June 2007 alone, less than half of whom have been identified - those were foreign civilians, not American soldiers. To a large degree, America has insulated itself from this type of loss.

Perhaps this makes stories like the one Hylton tells more, rather than less, important. Six decades later, the Arnett crew's disappearance still had the power to wound. As America slowly transitions out of more than a decade of fighting brutal insurgencies, we need books like Vanished to remind us of the long, painful aftermath of war.

Phil Klay served in the United States Marine Corps from 2005 to 2009 and was deployed to Iraq from 2007 to 2008. He is the author of the forthcoming short story collection, Redeployment, and is a contributor to Fire and Forget: Short Stories From the Long War.