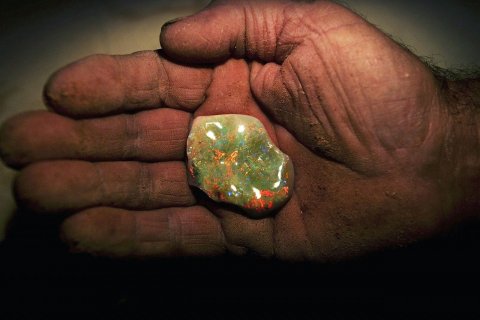

"When I see the earth, my palms get itchy," says Trevor Berry. The Adelaide native first came to the largely subterranean town of Coober Pedy in South Australia's mineral-rich outback on a school trip when he was 13. He thought it was "the biggest dump" he'd ever seen. But lured by the riches that lurk beneath the sands, he moved here for good in 1999 "to strike it rich."

"Opal mining is one of Coober Pedy's biggest attractions, but if you don't find opal, you don't get paid," says Berry. That's why most permanent residents plant one foot in the mines and another in the tourism trade; when he's not hunting the precious stones, Berry runs the Old Timers Mine and Museum.

As its residents never tire of reminding you, Coober Pedy is unlike anywhere else on Earth: The majority of its citizens live in underground dugouts chopped out of the red dirt to escape the inhospitable heat that bakes the outback's rear end. The mines here produce more than 80 percent of the world's opals, and since the discovery of the precious stone about a hundred years ago the town has filled with bug-eyed miners and slimy gem-cutters. And with the discovery of shale oil below the opals this past January, it may also be the site of what has been called the most important energy find in 50 years.

Flying into Coober Pedy from Adelaide you might be forgiven for thinking an army of giant gophers had invaded, leaving behind gaping holes, towering pits of rubble, and little else. These cavities are either opal mines or opal miners' homes and businesses - glorious underground churches, hobbit-like houses, and working mines.

Coober Pedy's subterranean level is speckled with some of the most incandescent stone on the planet. Vibrant, too, is the life its residents have carved out of this burnt-red earth. "When I first came here from Thessaloniki, [Greece] 41 years ago, I said, 'Oh, no! What have I done?' " Yanni Athanasiadis, longtime resident and owner of the Umoona Opal Mine, recalls as we tour his cheery underground home. "But I didn't migrate to Australia; I migrated to Coober Pedy."

It was a 15-year-old named Willie Hutchinson who first kicked up some opal and put Coober Pedy on the map 98 years ago. And it was soldiers headed south from Darwin to Adelaide after World War I who came up with the idea to build the trench-inspired dugouts for which the town is now famous.

Douglas Stewart, co-writer and narrator of the 1956 documentary The Back of Beyond, described this part of the outback as "little more than a bone-dry rut disappearing into a mirage over the edge of the world." For Athanasiadis, however, there is something special in this "never-never land," as it's often called. The lanky Greek has traveled the world selling his gems, but he always finds his way back to Coober Pedy.

"Look as far out into the distance as you can," he instructs me as we stand on top of a rocky outcrop known as the Breakaways. "What do you see? Nothing. But there's a beauty in this nothingness...and there are a lot of men who've found a lot of money here."

Opal occurs where silica gel fills small fissures or voids in the earth, says Berry. Unlike some other minerals, it's not something that big businesses can survey, identify, and drill out. Rather, it's a game for the individual - one who often spends his whole life in a virtual sandbox, digging holes and hoping to find buried treasure. "I had a miner friend tell me the other day that finding opals was as good as sex," he says. "It really is a big rush. And when you get that rush for the first time, you just want to feel it again."

Opal mining is a risky business that has lured hordes of Greeks, Serbs, Croats, Italians, and Germans to build one of Australia's most multicultural outposts in the middle of the desert. They have been joined by clans of formerly nomadic Aboriginals (who named this place kupa-piti, "white man's hole"), Chinese, Indians, and Sri Lankans to form a city of 3,000 people that is, well, unlike anywhere else on Earth.

Though many of the transient hospitality workers live and work above ground, most longtime residents prefer the calm and cool respite below the surface, which maintains a year-round temperature of between 73 to 77 degrees. Many, like retired miner Guenther Wagner, find the dugouts so comfortable that they can't imagine ever living above ground again. "Wherever you see a hill, somebody lives in it," Wagner explains in his thick German accent as he takes me on a drive out of town for a 375-mile loop into the outback. The Stuttgart-native was a photojournalist in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War, but traded his Leica for a shovel when he moved to Coober Pedy in 1969.

"I was traveling from Perth to Sydney and came to check it out," he says. "Three months later, I had my first share in the opal field. I made some good money and I said, 'I think I'll hang around here for a while.' Forty years later, I'm still hanging around."

On our daylong journey through the lunar-like landscape of the Moon Plain to the far side of the Dingo Fence (which is longer than the Great Wall of China), we pass just four other cars, though there are at least two dozen abandoned vehicles on the side of the road, many riddled with bullet holes. Highlights of the trip include a Painted Desert, a mob of emus, and a cattle ranch the size of Belgium.

Ranching may seem like an odd operation for the outback, so barren in appearance, but Wagner explains that Coober Pedy lies within the Great Artesian Basin, the remains of a vast interior sea that covered about a quarter of Australia's current landmass between 100 million and 250 million years ago. Europeans discovered in the 1870s that this underground reservoir contained a massive amount of water, equivalent to about three-times the volume of North America's Great Lakes, opening up a vast portion of Australia to settlement.

Now the discovery of oil has the potential to change the landscape surrounding Coober Pedy just as radically as water once did. Brisbane-based Linc Energy announced in January that two independent studies had confirmed between 103 billion and 233 billion barrels of shale oil in the Arckaringa Basin, worth upwards of $20 trillion. These Saudi Arabia-like figures, which would make Australia an oil exporter instead of another petroleum-thirsty importer, drummed up plenty of excitement and sparked all sorts of geopolitical discussions, but there were a few difficulties overlooked in the hubbub.

"We all thought, Wow. But there are problems with the shale," Athanasiadis explains over dinner at Tom & Mary's Greek Taverna Restaurant in town. "It's below the water base, and if they mine down there like they have done in the U.S., then they could contaminate the water for about 50 percent of Australians. All of Central Australia would be finished."

Shale oil is costly to extract and would require fracking, the hydraulic fracturing of rock by pressurized fluid, which is currently banned in some Australian states. For the amount of chatter this find has created in the blogosphere, few in Coober Pedy take much notice. And don't believe any of the reports that suggest this tiny town is gearing up to become some sort of Dubai-like desert mirage. Coober Pedy is content to keep its spectacle underground.

Looming over the dugouts, the grass-less golf course, the drive-in cinema screen, the opal stores, the underground hotels, and more than a million mine pits is a lookout known as the Big Winch. Hanging from the Big Winch is a barrel. And on that barrel is one word which could be the town motto: "If."