They attacked before the sun rose, toward the end of Ramadan. In the August heat, soldiers went from house to house in the small Alawite villages near the al-Akrad mountains, delivering death and terror. The inhabitants of this Western Syria governorate were farmers, simple people. Until that morning, they had been able to avoid the brutal fighting that has ravaged Syria for the past three years, spared the atrocities committed against civilians by the government soldiers of President Bashar al-Assad, or his notorious paramilitaries, the Shabiha.

The massacre that commenced that day was shocking in its brutality, but newsworthy for another reason: It was committed by jihadist groups fighting on the rebel side. In the Alawite villages, these rebels burned whatever possessions they found, including homes. They gunned down the elderly and the disabled. They shot those who fled in terror and executed some victims at close range. Young and old, men and women, infants and grandparents.

The murderers left bodies where they lay, to rot in the baking sun, but some corpses were later found in mass graves. One witness, a volunteer in the government's local militia, said he saw a woman's body hanging from an apple tree. Another said he saw a dead pregnant woman, her stomach slit open.

Human Rights Watch says 67 people from these villages were "unlawfully" killed, and that some corpses were bound - showing signs of execution. Others were decapitated.

One witness told investigators, "They had machine guns and were using snipers," adding that the men were "all dressed in black.... We hid, but my dad stayed in the house. He was killed in his bed. My aunt, an 80-year-old blind woman, was also killed in her room. Her name is Nassiba."

After the slaughter, the rebels took hostages - mostly women and children. According to sources in Damascus, the fighters, led by local jihadist groups as well as members of Jabhat al-Nusra and the al-Qaeda linked group, Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, are still holding more than 100 civilian noncombatants.

Some say the assault was retribution for a pro-Assad attack last May against civilians in the villages of Bayda and Baniyas, where 248 Sunnis were slaughtered. Others say it was to send Assad a message: Nowhere is safe.

The reason for the attack is not clear, but one result is indisputable: It did irreparable damage to the cause of the Syrian rebellion.

Last month, both the National Coalition of Syria and the Supreme Military Council - official bodies of the Syrian opposition - distanced themselves from the atrocities. The National Council of Syria called the crimes "a grave violation of human rights that must be addressed."

The official umbrella group of the Syrian opposition has condemned the killings and kidnappings, and says it has no contact with some of the jihadist groups responsible so it can't even negotiate for the return of the prisoners.

Najib Ghadbian, the special representative of the Syrian Coalition to the United Nations, says the opposition is "struggling to replace the regime with a democratic regime" and that the crimes have been condemned by the coalition, as well as the Free Syrian Army (FSA). "We are acknowledging [the crimes] and will condemn those men," Ghadbian says, stressing it was an "individualistic crime" and not the policy of the FSA.

Ghadbian also says the atrocities - while horrific - must be put in context of the past crimes the regime has committed. "[Crimes] they never acknowledge," he said from Turkey, where he is working with colleagues on negotiations for potential Geneva II talks. "From this war, there are 120,000 people dead; 9.3 million people displaced, and people killed by chemical weapon. From our side, we completely reject these crimes - we should not do what the other side does."

He also says between 50 and 150 people from the rebel side are killed each day, "mostly civilians, but some soldiers."

The civilians killed in this massacre were Alawites, an offshoot of the Shia faith. Not far from their villages, Bashar al-Assad's father, Hafez al-Assad was born, raised, and attended school in the village of Qardaha. It is here that the former president is buried, encased in marble, his tomb covered in fresh flowers next to his eldest son Bassel, who died in 1994 at the age of 32, and his mother, Na'asa.

The attacks were a clear message to the co-religionists of the family that has ruled Syria with firmness and often brutality since 1971. "It was a shot in the heartland of Assad's homeland," says Lama Fakih, the Human Rights Watch researcher who led the investigation of the Alawite massacre, which is becoming known as Operation Liberation of the Coast.

The massacre has been kept quiet by both the Syrian regime and the opposition groups. "It was as if [the Alawites] were too ashamed to talk of what they had thought would never happen again," wrote Reem Haddad, a Damascus-based journalist, referring to earlier massacres of the minority Alawites.

As more revelations of the slaughter are discovered, more and more Syrians - even anti-Assad activists - are disgusted by the civilian cost of the war. "People are fed up, frustrated with the opposition, we have lost faith," says Maryam, a Sunni in Damascus who once supported the opposition. "Why are we still losing our kids, our homes, our people?"

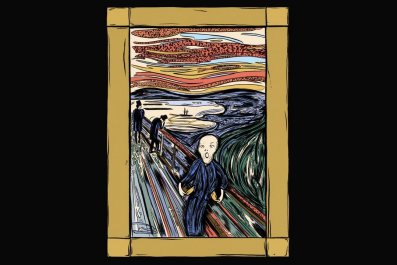

Many in Syria, and around the world, are also asking what turned the opposition from a group of peaceful protesters challenging the regime of Assad in the streets of Dar'aa into a gang of ruthless killers?

Since those early street protests - beginning in the spring of 2011 - the tide of the war in Syria has turned. Public sentiment - once on the side of the opposition that modeled itself on Spanish Civil War Republicans or Bosnian freedom fighters - has shifted. This is due, in part, to the fact that the Free Syrian Army has lost ground in many places to jihadists, who are now better armed thanks to generous funding from wealthy Gulf nations. Even if the under-armed FSA wanted to maintain order among the rebels, it often cannot.

The in-fighting between opposition groups is often fierce. Several Turkish border crossings have been taken over by jihadist groups, and aid workers have been attacked and kidnapped simply for trying to deliver humanitarian supplies. Cities such as Raqqa have expelled Free Syrian Army fighters in an attempt to make the city entirely jihadist.

All of this barely affects the political wing of the opposition, which has little connection to those fighting - and living - inside Syria. The question is - how did the opposition splinter so drastically?

"It's not as simple as the Syrian opposition turning nasty," says Peter Bouckaert, emergencies director of Human Rights Watch. "It's that the opposition has been hijacked by extremists from Iraq and elsewhere who imposed this sectarian agenda on this revolution."

Bouckaert first went to Syria in June 2011, before the armed resistance began. He traveled through Idlib, Northern Syria - now a no-go zone for reporters because of the high incidence of kidnapping - where he met with opposition leaders and asked why they were still insisting on peaceful protests when facing such oppressive violence from the Assad regime. "One told me: The day we pick up the gun is the day that Syria ends," he says.

Once armed conflict began, some figureheads of the movement - such as the Alawite actress Fadwa Suleiman who led the early protests in Homs - left the country. "There was always a feeling that resorting to the gun from a peaceful resistance was playing with fire," Bouckaert says. And the fire is now raging out of control. According to United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, there are more than 2 million refugees and a projected 2 million more on the way.

There is rampant disease - even polio, which has all been eradicated in most parts of the world - and widespread misery. Public institutions inside Syria have completely broken down. An entire generation of children, according to the U.N. high commissioner, has been out of school for three years.

"Since the beginning of the conflict, the Syrian government has used unimaginable brutality against its own people," says Bouckaert. "They started by shooting down peaceful protesters and torturing people to death, then began indiscriminately bombing their own towns and villages and committing countless massacres and executions, and ended up by gassing over a thousand people with chemical weapons in Ghouta in August."

What happened in Latakia is a reminder that Syrian civilians, not the politicians or the soldiers, are the ones paying most dearly for this horrible war.