As a child, Pasquale Contini dreamed of being a chef. He had to go to jail to fulfill his dream. Now he's a free man, and he claims the Italian state owes him more than 15,000 euros in wages for his work as head chef at a prison in central Italy, where he served a 10-year sentence for accidentally killing his mother.

A court near the town of L'Aquila agreed with him, ruling that prison workers should be paid two thirds the market rate and that Contini was paid less than half that. In 2012, the court ordered the state to pay him just under 13,000 euros, a figure that has since risen due to late interest payments and other fees.

So far, Contini has got nothing.

The chef joins a very long list of people and businesses owed money by the Italian state. Business groups say between 2008 and 2012, more than 15,000 companies were forced out of business because the state didn't pay its bills.

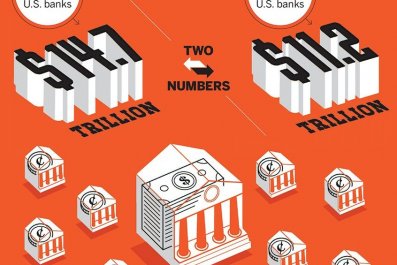

In January, the government did pay 22 billion euros in arrears to suppliers who provided services to the public sector. The newly appointed government has pledged to pay back the remaining 68 billion euros it owes suppliers by July.

But given Italy's status as the second most debt-ridden country in Europe after Greece, and its near default in 2011, that may not be so easy.

Contini's case has become a cause célèbre for those who say the Italian tax man is like a monster with deep pockets and arms of different lengths: The long arm is quick to reach into people's pockets for tax revenues; the short arm can't reach deep enough in its own pockets to pay what the state owes to suppliers and citizens.

Contini was jailed in 2001 after being convicted of non-culpable homicide for striking and killing his own mother by mistake while he was trying to defend her from his brother's regular violent fits.

"I've always had a passion for cooking," says Contini, now 64, unemployed and living off a disability pension of 250 euros a month.

"Ever since I was 5, I loved watching my mother handling pots and making tomato sauces. I attended hotel management school, and for a while I worked at a VIP restaurant," he says. "Cooking in prison made my stay more endurable."

Twice a day, Contini prepared Italian favorites like spaghetti Bolognese and spezzatino beef stew for prisoners in the mountain town of Sulmona, about 100 miles east of Rome. Menus extended to diabetic and low-sodium dishes for those inmates whose stomachs couldn't handle spaghetti carbonara or salted cod.

For five years, Contini toiled in the prison kitchen, working his way up to head chef. Italy's constitution protects prisoners' right to work and to be fairly compensated for jobs performed in jail, which are supposed to contribute to the prisoner's rehabilitation and return to society.

The court ruled not only that Contini was paid just a third of what would be paid to a comparable worker under standard labor contracts on the outside, but also that the prison neglected to pay part of his annual leave, holidays, overtime, a Christmas bonus and severance pay.

"The judge has ruled that the state owes my client a total of 15,469.63 euros," says Contini's lawyer, Fabio Cantelmi. "But two years after the verdict, and even though the Justice Ministry has never filed an appeal, we haven't seen a penny.

"How can a state refuse to pay?" asks Cantelmi, who is working pro bono for his client. "How can it pretend to enforce the law if it ignores a court's ruling? It's utterly unacceptable that if citizens dodge the tax man they get stalked and prosecuted, whereas the state can afford to do as it wishes."

Contini says he is desperate for the money: "I need to survive, I've got debts and bills to pay, I'll soon get kicked out of my house."

Frustrated in his appeals to the Justice Ministry to pay up, Cantelmi took his client's case to Rome, lobbying politicians for help. Gianni Melilla, a member of parliament for the leftist SEL Party, took up the cause, sending an official letter to the ministry demanding the chef be paid.

"Ever since the birth of Italy's republic in 1948, the state has been piling up tons of debts simply because its pockets are empty. It has run out of cash," Melilla tells Newsweek.

The Justice Ministry says a response to Melilla's letter will be sent to parliament in due course. "The sentence is definitive, there has been no appeal so it's irrevocable," says Deputy Justice Minister Enrico Costa. "The sentence must therefore be executed."

But he can't say how long that might take. "There are bureaucratic processes that need to be respected," he says.

As for Contini, he's been helping out at a homeless center, offering his cooking skills for free.