"Last night, after I did this show, someone gave me an envelope.... "

Rosanne Cash is sitting in a restaurant in Manhattan's Chelsea district, a few blocks from her home, talking about a gig she played in Troy, N.Y., the night before. "I was really tired, I didn't read it 'til this morning. It was from this woman who I met when I was 12 years old." The woman had been a creative writing teacher at a boy's prep school in Ojai, Calif., near where Cash lived with her mother, Vivian Liberto—she and her father, Johnny Cash, were splitting up that year—and she recalled in her note, "You told me that you wrote poems and asked me how you could turn them into music." She gave the young Cash a book of Rod McKuen's (an influence she thankfully outgrew).

"I had completely forgotten," says Cash, "but I remembered the book and poring over his poems. What was weird to me is that I have said for years that I wasn't interested in writing songs until I was 18—but clearly I was, even from 12 years of age."

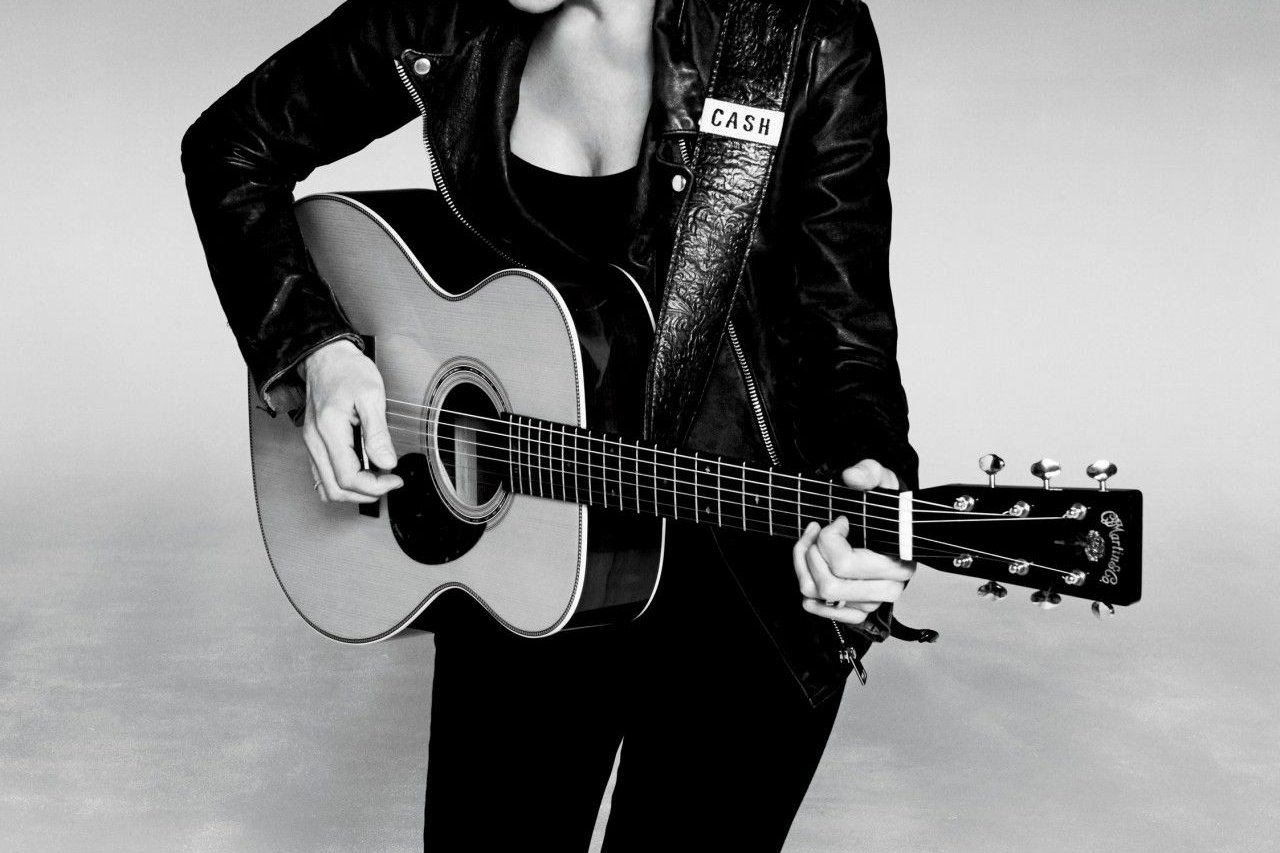

Cash established her songwriting bona fides since then (21 top-40 country singles since her debut album in 1979, and 11 of them No. 1 hits) and her new album, The River & the Thread, sounds like the work of a lifetime—in both meanings of the term. "These songs, I feel like I wrote 'em in a year's time but I wrote 'em in 35 years plus a year's time," says the 58-year-old singer. "I think you've got to put in the hours—the Malcolm Gladwell hours—and the veins get easier to tap. Sometimes. But sometimes you run right back into the wall. "

We had been talking about memoirs we liked—she published a doozy in 2010 entitled, appropriately, Composed—and Bob Dylan's Chronicles made the list (though, she adds, "I don't believe half of it"). One of its less celebrated chapters describes his efforts to record O Mercy!—the head-banging even the mighty Dylan admitted to while trying to eke out a lyric. "I know the experience of being a coal miner: 'moon' and 'June'—and suddenly something opens out for you," she says.

The River & the Thread began when Arkansas State University enlisted Cash's support in its effort to buy and preserve her father's boyhood home in Dyess, Ark., in 2008. In the course of visiting the old farmhouse and fund-raising for the project, she and her husband and longtime musical collaborator John Leventhal began a literal and metaphorical exploration of the region—Highway 61, Memphis, the Mississippi of Robert Johnson and William Faulkner. Though Cash lived for a while in Nashville, she was born and raised in California, spent time in Europe and has called New York home for more than 20 years. What began as an exploration of the South became something more personal.

"At some point, after the first few songs, I said, 'We have to write all this together and make that the framework,' " she recalls between bites of beet salad and grilled octopus. She even suggested that both of their names and pictures appear on the cover of the album—a suggestion her husband politely declined. "But by the time we did 'Night School' I saw that even if the songs weren't about our marriage, the process was. We were framing each other's best selves and bringing out the best in each other rather than competing. And in the best sense, that's what marriage is, right?"

Her personal songs have always been very personal, and writing has been an act of faith for her since she was a teenager. She abandoned the Catholicism of her mother, with its act of contrition. "None of that mattered," she wrote in her memoir. "I was a writer. It would save me." And while she has written and sung of her trials—divorce, death, miscarriage and a variety of illnesses, from the throat polyps that nearly claimed her voice to the brain surgery she had in 2007—she is not an open book. "People think I'm confessional and they know everything," she says. "Not even close."

"Night School" is one of the more haunting tracks on her brilliant new album. She set it in Mobile, Ala.—a place she'd never been and had researched largely via the Internet. "I knew there would be magnolia trees and it would be really hot and steamy. I was at a sad point in my life, and I just saw this couple wandering around this empty house."

The story of a middle-aged couple haunting a place where "hungry ghosts still tap the walls / Where once there was a door" doesn't end well:

Steam lies on the windowpanes

We acted like such fools

But I'd give everything to be

Lying next to you

In night school

"They had damaged things beyond repair but they still loved each other," says Cash. "John and I have felt like that; I think every couple who has been married a long time has felt, 'I've damaged it and I don't know how to get it back.' And if you're lucky, you get back. We did, but that other couple didn't."

When I spoke to Leventhal later he declined to talk about the song in terms of his marriage but told me, "I've played that song for grown men who have been married a long time, and maybe seen a marriage end, and seen them choke up. It's hard not to have a sense of regret, looking into that slightly empty room."

He speaks of his work as a pro: "It's what I do, I write for a lot of people, produce records." (For his ex-lover, Shawn Colvin, for instance; and his wife's first husband, Rodney Crowell.) He not only produced The River & the Thread but plays guitar and a variety of instruments throughout. He says it's the best work they have done together, and her best lyrics ever. He can't explain how he meets his mate musically. "I'm a sponge who has soaked up a lot of music," he says. "I love Howlin' Wolf as much as I love John Lennon," and blues and pop thread through the album along with swatches of country and pieces of gospel. "I try and turn off my analyzer and respond emotionally to it," he says. "When you collaborate with anyone, you can't be too rigid about your stuff. You have to modify."

Again: sounds like a marriage. Cash appreciates their differences ("The two of you would make one great person," an astrologer once told them after reading their charts). "He's so much more rational, so much more in the world," she says of her husband of almost 19 years. "He knows about money. He knows how to turn the boiler on." And Leventhal is a fourth-generation New Yorker with a Cuban-Irish mother and a Jewish father. Before they were married by a rabbi, her father said, "I've been waiting 40 years for one of my daughters to marry a Jew."

Leventhal tends to think of himself as a New Yorker first. "When I'm around gentiles I feel Jewish, and when I'm around Jews I feel gentile," he says, adding that his wife is even more of a New Yorker than he is. "There are times I'm willing to let it all go," he says. "She's out there wanting to embrace New York in all of its enormity."

Cash abandoned Nashville for New York after the head of Columbia A&R there rejected Interiors, her 1990 album inspired by her breakup with Crowell. "After listening to four songs he laughed coldly and said, 'We can't do anything with that,' " she wrote.

"A peripatetic person can feel very at home in New York because of the pace," says Cash. She looks tired after racing up to Troy and back for last night's concert. "We're doing strategic strikes in touring" in support of the album, she says (they will be at San Francisco's SF Jazz Center for four nights in April). "We go out for two or three days and then get back and take care of our child" (Jakob is 14; she has three grown daughters from her previous marriage, one of whom lives in New York). "I think he needs me more now than when he was a toddler-though Jake would say he doesn't need me."

It's tough for most parents to connect with their teenage children-and vice versa. I ask if she spoke to her father about the craft of songwriting when she was a child. I had been warned by her publicist that Rosanne got tired of talking about Johnny Cash—her 2006 Black Cadillac reflected on the death of both of her parents, after all and The List (2009) was another form of tribute, having been culled from the inventory of what her father had told his daughters were essential country songs. Enough already. But if your dad was one of the country's premier songwriters and a legend—he's got his own damn stamp—it's hard to avoid the topic. Did she ask him about songwriting?

"Not until I started writing songs," she says. "Also, you know, he was a drug addict for most of my childhood. But I did write him a letter when I was 12 years old which he saved." That was the year she asked the writing professor about turning poems into songs, and the year of her parents' divorce. "I'd had this burst of expansiveness about who I was. I told him I wanted to do something special, that I loved art and music, and I wanted to be out in the world, and I didn't want to be just a wife and a mother-I poured my heart out to him.

"And he wrote me back this letter that ached with identification. It was so great. And he said, 'I see that you see as I see.'

"I'll never forget that line."