I am in love with a cougar. She is an octogenarian, an old-fashioned dame who won't be cowed by younger rivals adorned in flashier vestments. She has lost some luster, true, but she is about to regain it. And when she does, you will understand why I gaze longingly at her from the Brooklyn Heights Promenade, as tourists jostle to take pictures of lesser beauties that have long been stripped of any mystery.

Her name is 70 Pine Street, and she is the premier art deco skyscraper in the Financial District of lower Manhattan. Built in 1932, she was the third-tallest edifice in the city at the time, eclipsed only by the Empire State and Chrysler buildings. Today, she is the eighth-tallest building in the city, having been overtaken by glass towers that have less soul than a bowl of Cheerios. But she has a quality that cannot be measured: something called grace.

It has been several decades since 70 Pine has been open to the public. Few citizens of or tourists to New York City have seen its splendid lobby, bathed in gold and touched by silver. Far fewer have been to its observatory on the 66th floor, a magnificent glass bubble hovering above Wall Street. But that will change next fall, when developer Rose Associates opens the building as a rental property, hotel and retail hub. Having languished for years, 70 Pine will make her debut. Once again.

The building, which was erected at the height of the Great Depression, was filled with the latest technology, according to Daniel M. Abramson's book Skyscraper Rivals, "including hot-water heating and double-deck elevators, plus an in-house gymnasium and law library." Those two-story elevators, long gone, were staffed by comely operators who were, according to Abramson, "recruited largely from the ranks of unemployed showgirls." This, unfortunately, will not be part of the new 70 Pine. The gym, meanwhile, was run by Artie McGovern, who trained the likes of Jack Dempsey and Babe Ruth.

"The most beautiful building of all," opined the midcentury photographer Weegee.

Height alone is hardly a precondition for beauty. And though 70 Pine, at 952 feet, easily towered over rivals like the Woolworth Building (792 feet), what made it truly distinctive was its narrow profile: "If it was a model, it'd be all legs," says Mark Foster Gage, assistant dean of the Yale School of Architecture. With a series of artful setbacks and a roof tapering into a spire, 70 Pine looks like a needle pricking heaven's underbelly. And though it is composed of 10 million bricks and 24,000 tons of steel, it seems endearingly fragile, a forlorn figure lost in dusky thought.

At street level, 70 Pine announces itself magisterially with a band of maroon Brazilian granite, then, above that, Indiana limestone carved with art deco motifs. Aluminum metalwork includes, according to a report by the city's Landmarks Preservation Commission, a "relief depicting pairs of butterflies with outstretched wings pecking at sunflowers, a possible allusion to oil production." (The building's owner and main tenant, the Cities Service Co.-much later, Citgo-owned 6,000 oil wells and eight refineries.)

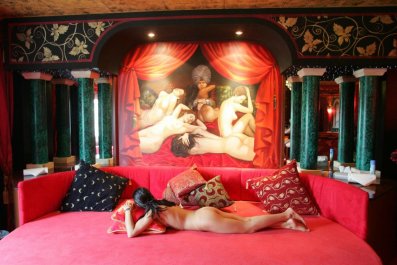

To call what awaits beyond the door a "lobby" is to give a pedestrian name to an ethereal chamber, an amber cocoon of marble that smiles like a thousand happy children. The injunction of Cities Service founder Henry L.. Doherty to his architects to abstain from "the garish, the flamboyant and the over colorful" was thankfully disregarded. The entrances to about two dozen elevators are decorated with patterning that recalls the Native American art of the Southwest, as well as the light-radiating triangle that was the Cities Service logo.

Even more flamboyant is the 66th floor's glass-and-steel observatory, which is only 23 by 33 feet—as small as a studio, but as splendid as a mansion. Doherty had planned to make this into a penthouse apartment, but arthritis drove him to a sanitorium in Michigan and the warm climes of Florida. Architecture historian Christopher Gray wrote in The New York Times, "To stand in this exhilarating room is like being in a cube of quartz at the roof of the world, transparent all the way round."

Great architecture is pointless if it remains unseen, and too many buildings in Manhattan remain inaccessible to the public: Until recently, it was essentially impossible to see the lobby of the Woolworth Building, with its vaulted ceilings and Gothic accents. Though the observatory of 70 Pine was once open to the curious (for 50 cents), it has been closed since. American International Group, a villain of the Great Recession, bought it in 1976. AIG appears to have been a sound custodian of 70 Pine, but not a welcoming one. According to people familiar with the building's history, AIG did not permit the public into the lobby or up in the observatory, which was reportedly used for high-level executive wooing. How many of the "financial instruments" that almost sank our economy were toyed with in these exquisite confines? At such delusive heights, hubris could prove combustible.

The structure wound up in the hands of Rose Associates in the spring of 2012. The firm is a storied real estate family operation headed by cousins Amy and Adam Rose. The plan is to offer 644 rental apartments starting next fall. The building will also feature an extended-stay hotel of 132 units, a luxury gym and a high-end restaurant that aims to be a destination rather than just a red-meat fallback.

"The building has a grandeur," says Adam Rose, who went to Yale and dreamt of being a cop (he recently married one), but ended up working in the real estate firm founded by his great-uncle, David Rose. He bemoans both the "cheap and cheerful" new constructions that plague lower Manhattan, as well as the "gold-plated nonsense" of Donald Trump. He says 70 Pine will be "expensive but attainable," with interiors by noted architect and designer Deborah Berke. Rose says of his ideal residents, "These aren't supermodels or trust-fund brats."

Of course, the notion that aspirants to that much-maligned 1 percent even want to live in the Financial District would have seemed preposterous while Ground Zero remained an open wound on Manhattan's face. More recently, this neighborhood was nearly swallowed by Hurricane Sandy. And yet this spit of land the Dutch settled four centuries ago continues to reinvent itself. An uncle who used to work down here in the 1980s used to sleep in his office rather than risking what was then a perilous walk to the parking garage. Today, that stroll would be threatened only by dog walkers.

Because the building's exterior and lobby are landmarked by the city (the observatory also has a historical-significance designation), Rose could only minimally tinker with those elements. He says the building will be merely "refreshed"—unlike, say, the Hearst Corp. headquarters in Midtown Manhattan, an art deco jewel crowned by a Norman Foster glass tower that looks as flagrantly unbecoming as a beanie on a Fifth Avenue dame.

Cass Gilbert, the famed architect whose creations (including the Woolworth) stud Manhattan, once called the skyscraper "a machine that makes the land pay." Rose talks about 70 Pine with a lover's adulation, but the kind of rents that have been bandied about suggest that this little parcel of lower Manhattan will reap its owner dividends soon enough.

While the apartments themselves will remain for the rich, Rose does plan to open up as much of the lobby as possible, stocking it with workaday retailers that both the glamorous and the ordinary need; a lounge or club will operate on floors 62, 63 and 64. The plans for the 66th-floor observatory are not yet clear, as it is not only small but difficult to access.

My love for this building has long been unrequited and misunderstood, my ecstatic allusions to 70 Pine met with confusion, even from seasoned New Yorkers. For 40 years, this skyscraper has offered nothing to the city but an expressionless stare of the sort you encounter on the subway on a Tuesday morning. And so the city has forgotten a building it has not been allowed to love. But come next fall, the romance will rekindle.