It sounds like one of those superhero films where Spider-Man and the Mighty Thor join forces with Iron Man and Captain America to save the world.

In this case Gandalf, the wizard of The Lord of the Rings, and Captain Jean-Luc Picard of Star Trek: The Next Generation, who also go into battle in X-Men, have teamed up with secret agent James Bond in a mission to penetrate an alien citadel.

Or, to put it another way, venerable Shakespearean actors Sir Ian McKellen (Gandalf/Magneto) and Sir Patrick Stewart (Picard/Professor X) have been executing a pincer movement with action hero Daniel Craig (007), to assault the theater audiences of New York with the work of England's most enigmatic modern playwright.

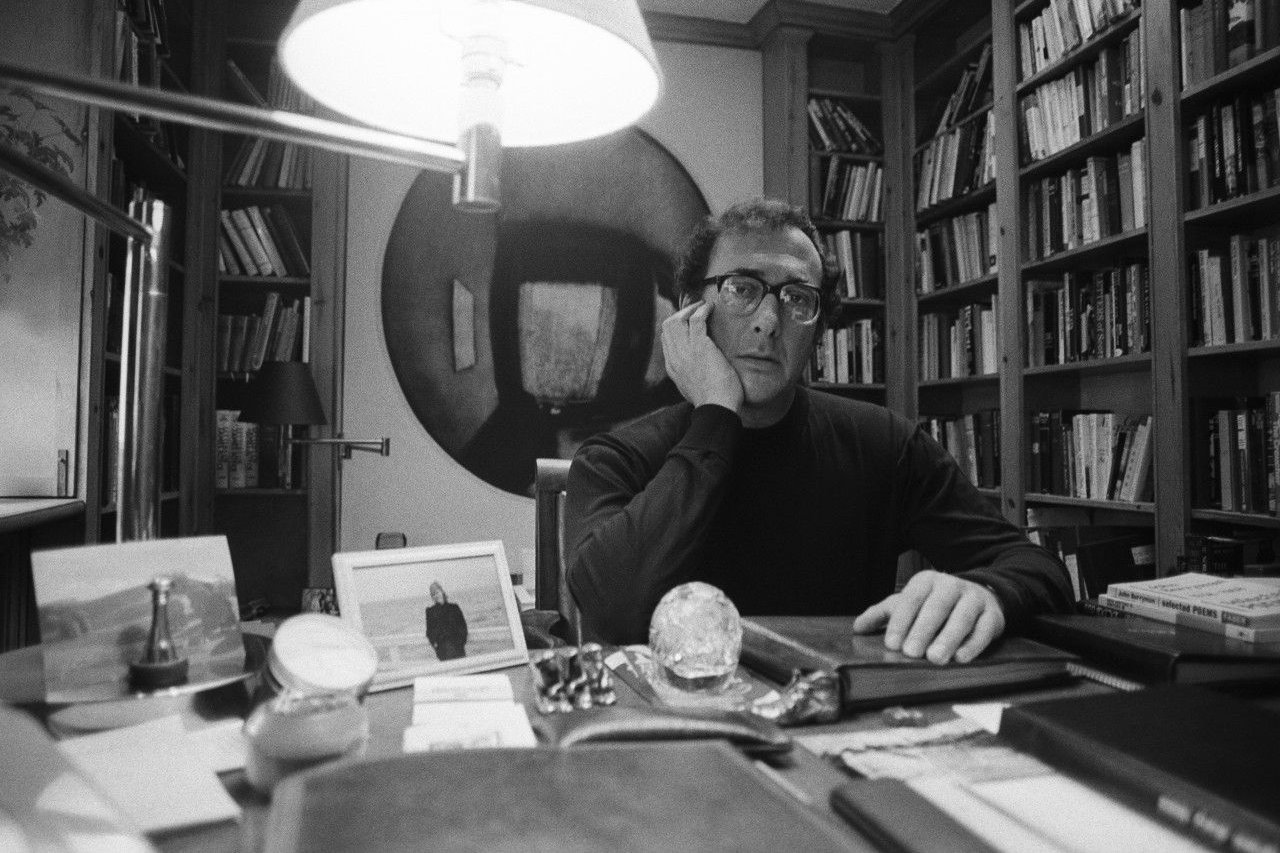

An already risky venture for these stars of blockbusting screen franchises can't have been made easier by the fact that the playwright in question, the late Harold Pinter, was a famously outspoken critic of U.S. foreign policy and Great Britain's role in supporting it.

After the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, Stewart starred in a Broadway production of Pinter's The Caretaker. "When we opened a very good production," Stewart recalls, "we invited Harold to come and see it and he sent us a letter explaining that due to the present U.S. administration and its policies, for him to set foot on American soil would be a tacit approval of American foreign policy."

In his 2005 Nobel Prize in Literature lecture, Pinter described the United States as responsible for "systematic, constant, vicious, remorseless" crimes against humanity.

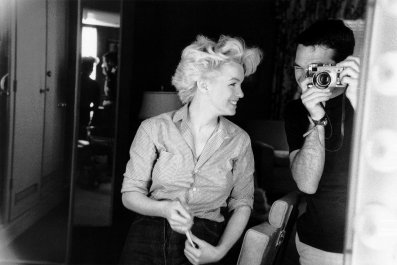

Despite all this, Pinter's Betrayal at New York's Barrymore Theater, a dissection of an adulterous affair starring Daniel Craig and Rachel Weiss, sold out as soon as the tickets went on sale and remained a sellout until the end of its run.

Betrayal may have an unusual back-to-front narrative structure, but it is among Pinter's more accessible works. No Man's Land, which appears at the Cort Theater in rotation with Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot, both starring McKellen and Stewart, is a different kettle of fish altogether. It was described by the legendary London theater critic Kenneth Tynan as "gratuitously obscure," while the mischievous Pinter once told another critic he didn't understand it himself.

The 1975 opening of No Man's Land coincided with Pinter's love affair with the historical biographer Lady Antonia Fraser, recalled in her memoir Must You Go?: My Life With Harold Pinter. On the first night she writes that the London Evening Standard critic, after admitting he had fallen asleep during the performance, was so baffled he asked her if she could explain what the play meant.

She ventured an interpretation then, but tells me now, "I never comment on the meaning of Harold's plays. Didn't he once say: 'It means whatever you think it means'? Spoken lightly or not, it has always struck me as a pretty good answer."

Yet Broadway audiences, it seems, have been lapping it up. "I have never before heard American audiences respond to any production of Pinter or Beckett with such warm and embracing laughter," wrote critic Ben Brantley in The New York Times. "This isn't just a matter of theatergoers chuckling to show that they are smart and cultured," he added. "The audience is truly in on the joke."

So what is No Man's Land about? And what exactly is "the joke" that New York audiences are now in on? The play takes place in the drawing room of a large house in Hampstead, a leafy north London suburb, and a famous haunt of liberal intellectuals. Hirst (Stewart), an aging, but once successful writer, arrives home with another elderly man called Spooner (McKellen), who claims to be a poet.

Hirst in particular consumes spectacular quantities of whiskey, while they appear to trade reflections on life. Yet it is unclear if they know each other or have just met by chance, or if anything either of them says bears any relation to real events.

The only other characters are Hirst's employees: his secretary Foster (Billy Crudup) and his vaguely menacing housekeeper Briggs (Shuler Hensley). In Act II, Hirst behaves as if he has known Spooner for years, but addresses him by a completely different name. Unfazed, Spooner plays along.

The play can seem so perplexing that director Sean Mathias, a former partner and old friend and collaborator of McKellen, had to resort to a kind of subterfuge to get the great man on board.

"Ian was baffled by it," he said. "He just didn't understand it. My partner said, 'Why don't you tell Ian that if he does the Pinter, you'll take the Godot to America? And why don't you tell Patrick that if he does the Godot you'll take the Pinter to America?' And I thought that nutty piece of opportunism had legs."

Once on board, McKellen had two problems to wrestle with: his grasp of the play's meaning and the ghost of what was seen as a definitive first performance by the late Sir John Gielgud. It was the process of rehearsal that brought clarity, he told me.

"Suddenly things which seem insuperably complicated and obscure melt away. I'm a very literal person and have to be told off about that a lot: 'Don't take it too literally! Don't bring it down to what he had for breakfast!'

"Any actor of my generation is stuck with a post-Freudian interest in characters. Well now I've arrived at a situation where I know with absolute certainty that my character Spooner has never met this man Hirst before. He's an optimist who toadies up to the great man in the hope of a free billet for a bit. He's a chancer, but everything he says about himself is true in spirit, albeit exaggerated."

Stewart's character Hirst can seem even more elusive. He is obsessed with memories prompted by a photo album and seems to be haunted by an old tragedy involving water. But for Stewart this reflects a particular type of mental condition and one which will be all-too recognizable to audiences from any culture.

"I don't believe there's any fantasy in this play," he said. "We never went for abstractions. For one thing, I wouldn't know how to act an abstraction. We have rooted everything in a researched and comprehensive reality." At Stewart's suggestion, the distinguished British neurologist and writer, Oliver Sacks, talked to the cast, who then performed some scenes for him.

"It was an extraordinary afternoon," said Stewart, "to have Oliver talking about aging and the impact of memory loss, and it became increasingly clear to us that this is where the issues for Hirst reside. So on the basis of that, I found that the contradictions and non sequiturs could all make sense when put in the context of someone who is not only aging badly but is also a severe alcoholic. Oliver pointed out to us that senility, Alzheimer's and aging are serious problems, but that they are magnified many times over if they are accompanied by heavy drinking."

McKellen concurs. "Oliver Sacks was brilliant," he said. "He said that Hirst is a standard case of dementia brought on by old age and drink and these can cause severe situations in which people mistake their friends and their acquaintances for a whole range of characters who are just living inside their head.

"You, as an outsider, have two options: You can go into that world and pretend to be the character you've been cast in. Or you can try and drive the person back into the so-called real world. But that is a dangerous thing to do because they might get confused and violent."

Both actors have their Pinter anecdotes. As a young man McKellen was alongside Pinter's first wife, Vivien Merchant, in the film Alfred the Great, about the early English king. "When Pinter saw the script, he told her, 'If you speak any of these lines, I'll divorce you!' " said McKellen. "So she didn't. The director gave all the lines to me, and she got all the close-ups."

Stewart recalls asking Pinter whether a character he was playing should have a Welsh accent. "He asked me, 'What does it say in the play?' as if it had been written by someone else." Stewart then read back an illogical and inconclusive exchange of dialogue. "There you are," Pinter said to the baffled actor. "There's your answer."

Pinter's eccentricities aside, why should a play about disappointed ambitions, intellectual pretension and mental disintegration have Broadway audience chuckling merrily. One answer is that the dialogue is so beautifully crafted. Mathias and Stewart both talk about the special rhythmic quality, rooted in Pinter's love of poetry. "When you speak it, you realize that it falls naturally into blank verse," said McKellen. "And blank verse is the closest poetry gets to natural speech."

According to Professor Robert Gordon of the Pinter Centre at Goldsmiths College, London and author of Harold Pinter: The Theatre of Power, the roots of Pinter's style lie in his early acting career. "The sort of plays he was in were well-made plays by Terence Rattigan or Noel Coward," he said, "and it seems to me that he just turns them inside out."

Mathias agrees. "No Man's Land is a drawing-room play," he said, "and we decided if we start mucking around with that we will come a cropper. We must go for the drawing-room manner the whole time, imagining Coward or Rattigan had written it." This old-fashioned, very British delivery, all agree, make the absurdities and disjunctions in what is said all the funnier.

Even so, the sheer pleasure of the audiences, both on Broadway and in a trial run at the Berkeley Rep in California, came as a surprise. "Something that surprised me about audiences here," McKellen mused, "is that they don't seem to object to the fact that in the first act two people are drinking themselves stupid. In a country where alcoholism is a serious problem, you would have thought that was not perhaps a subject for comedy."

"I think some Americans would be much more disturbed by Pinter if they knew more about his real politics," says Gordon.

"Don't confuse Harold's reaction to the American government and certain of its policies with his reaction to the American people and indeed the United States itself," said Fraser. "If you take the example of the Iraq war, Harold certainly denounced it, and the American government's actions. But he also denounced his own government equally.

"We spent more time in the United States than in any other foreign country, always with pleasure. Harold had many American friends, both professional and otherwise. He directed in the U.S., acted there and at one point used to point out that his plays did better in the U.S. than in the U.K.

"I will hazard the opinion that Harold would have been absolutely thrilled by the present success of his two plays on Broadway. The first thing Daniel Craig said to me when we met after Betrayal was 'I wish Harold was here to see this.' I agreed with him totally."

Paul Hoggart's new novel Man Against a Background of Flames (Pighog Press) is available in the U.S. from Amazon.com