"Who giveth food to all flesh, for his mercy endureth forever."

- Psalm 136:25

And so it comes to pass that the drug cartels give and endure, with little mercy and a lot of help from YouTube.

In a video that has been circulating on the web since Tuesday, January 7, members of the Gulf Cartel, one of the largest in Mexico, are shown handing out cakes traditionally eaten by Catholics during the week leading up to Epiphany. They visit what appear to be schools, hospitals, nursing homes and impoverished neighborhoods in northeastern Tamaulipas state, giving away the colorful, sugary treat to residents who at times look eager, and at other times apprehensive.

"We take care of our people and always help," reads a caption embedded in the video, albeit with spelling errors. Shaky and out of focus, the video appears to have been shot with a handheld camera and edited at home. In the opening scene, six boys smile nervously as they hold two-foot-wide cakes, shaped like elongated donuts with red, white and green embellishments - the colors of the Mexican flag.

While President Enrique Peña Nieto focuses his efforts on - and channels international attention toward - Mexico's healthy economy and his signature education, tax and energy overhauls, criminal organizations are tightening their grip on vast regions of the country and showcasing their triumphs on increasingly public platforms, say analysts such as Pedro Isnardo de la Cruz, a security expert at Mexico's National Autonomous University.

The viral video, they say, is the latest weapon in the less violent but still devastating side of the drug war: narco public relations.

Cartels have long been known for their brutal methods. For years, people trembled at the thought of Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar, who eventually controlled more than 80 percent of the cocaine that entered the United States. "To Escobar, it didn't matter whether you were a man, woman or a child. If you were going to die, you were going to die. If he had to kill the father, he'd kill the whole family," says Max Mermelstein, a former drug smuggler, in "The Godfather of Cocaine," a 1997 Frontline special.

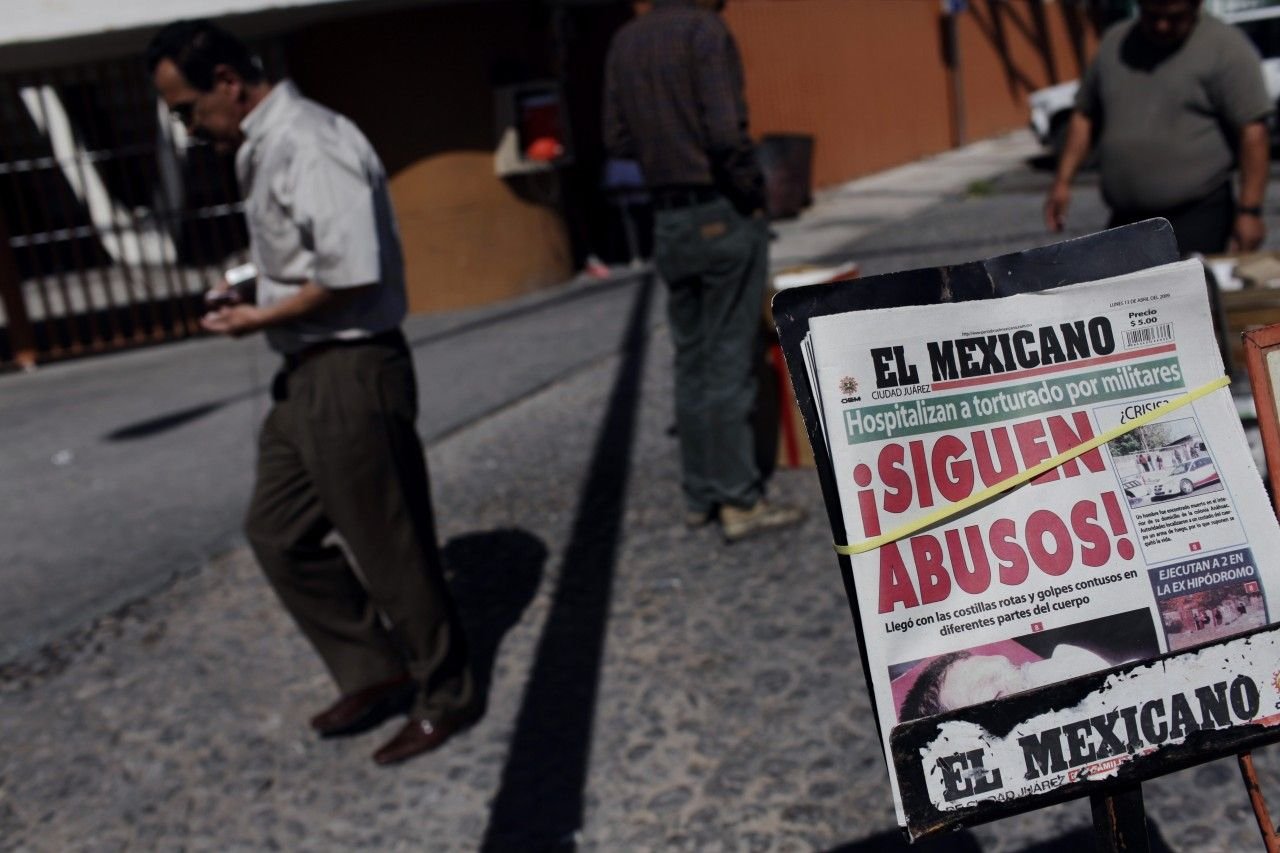

When former president Felipe Calderón declared war on Mexico's criminal groups in 2006, he indirectly unleashed a new level of ghastliness. Cartel thugs have thrown human heads onto busy dance floors; they have sewn the face of a victim to a soccer ball; they have hung nearly naked bodies from bridges above busy highways.

But the drug kingpins have always known that a little sugar was needed to improve their rapidly deteriorating image. Helping the communities in which they operate encourages the population to "not see them as enemies but rather, as people who can help, so that when there is a police operation, the community does not report them," says Jorge Chabat, a drug and security expert at CIDE, a Mexico City research university. It also sows the seeds for future recruits, Chabat added.

In the 1980s, Escobar built soccer fields and public housing, invested in reforestation programs and paid for street lighting projects. He became so beloved in some parts of Colombia that in his portrayal of Escobar's death, painter Fernando Botero included a tearful woman beneath the drug trafficker's bullet-ridden body.

Some drug barons are also known for their efforts at moral guidance. In 1995, Osiel Cárdenas Guillén, the longtime reputed leader of the Gulf Cartel, sent a large shipment of toys to Tamaulipas. As clowns entertained the crowd, a woman handed out dolls, bicycles and roller skates to the children. Attached to each toy was a sticker that read, "Perseverance, discipline and effort are the basis for success. Keep studying to be a great example. Happy Children's Day. With all my warmth for tomorrow's triumphant one, wishes you your friend: Osiel Cárdenas Guillén."

Members of criminal syndicates in Mexico are also known for giving alms to churches and throwing public children's parties.

The cartels, like the mainstream media industry, have adapted to an increasingly digital landscape. No longer are narcomantas, the vinyl banners which criminal groups place around cities to send out messages both to the general population and to rival cartels, enough. Now, these groups are making social media a key part of their communication strategy.

"They are looking to innovate their dialogue with people," said Isnardo de la Cruz. Tools such as Facebook and YouTube "allow them to construct a more effective communication system, with a greater reach."

A Facebook group called "Cartel del Golfo - CDG", created on Monday, January 6, regularly uploads photographs of its members with their faces blurred out. In the pictures, the men - and a few women - show off their gold-plated guns, stand in combat position at cartel checkpoints along highways and rest on boulders surrounded by large trees. One caption explains that they are battling a rival cartel in order "defend" their grip on the city.

In 2011, a video appeared on YouTube showing two dozen men huddled together. Dressed in black, their faces covered up and their hands firmly gripping rifles, they stare into the camera as a voiceover explains their objective: to rid Veracruz State of the Zetas Cartel, which had been terrorizing innocent residents. "Since 2006, we have been fighting for the tranquility and safety of each and every one of our compatriots in the state," says the voice.

In September, after Mexico's Pacific and Gulf coasts were simultaneously ravaged by tropical storms, a video emerged, showing members of the Gulf Cartel handing out relief to victims. Like many other videos of its kind, it was uploaded by ElBlogDelNarco, a website run by a private citizen who frequently publishes graphic reports and photographs of massacres across Mexico. Tips from the general population are the website's main source of information, according to the administrator. "Blog del Narco is not against or in favor of any criminal group," says its About page, which describes the website's mission as informing "with much more efficiency, veracity and better documentation than many other sites and professional journalists."

The relief video gained popularity as the government came under attack for what many in Mexico perceived to be a slow and inefficient response.

Shortly after Christmas, ElBlogdelNarco uploaded a video, nearly seven minutes long, showing members of the Gulf Cartel giving out free dinners to adults and toys to children in Reynosa, Tamaulipas. In the video, cartel members go to the public hospital, the main bus station and the historic center, drawing crowds and handing out pizzas. Parents lead their children by the hand toward trucks where men are disbursing the gifts. In one scene, the men and women taking these handouts loudly cheer on the cartel.

The authorities? Nowhere to be found.

Some analysts say videos like these, meant to garner support from the population and to shake rival cartels up by reminding them that their gang is still operating in a given city, show just how extensive the vacuum of power is in Mexico and how easily it is being filled by criminal groups.

"It is a critical sign, very complicated for the country, that organized crime and narco-related issues are not improving," said Isnardo de la Cruz. Instead, he said, cartels are "adapting to the new realities of virtual communication."