In mid-October, Sudanese telecom billionaire Mo Ibrahim stood before a packed roomful of journalists at a London hotel and hinted that he had bad news. "This is the reality. This is the mirror we hold before Africa today," he said, subtly letting on that his Prize for Achievement in African Leadership - a $5 million check, plus a $200,000 annuity - would, for a second year in a row, go to no one at all.

No leader from any of the continent's 54 countries had fulfilled the requirements of the prize, which seem amusingly modest. To qualify, a democratically elected leader deemed to have governed well must: (1) step down at the end of his constitutionally mandated term, and (2) get ready to cash Ibrahim's huge check.

"We made it clear from day one that the award is an award for excellence in leadership," Ibrahim defiantly told the South African newspaper Business Day after his dispiriting announcement in October. "It is not a pension for anybody who retires. It is an award for excellence," for people who have "no blood on their hands," and no "messy [legacy] of hanky-panky."

When the award was announced in 2007, the proposition seemed charmingly simple. On a continent where it is common for leaders to cling to power, Ibrahim was sending a message to would-be dictators: Give up being president for life in exchange for a fat lifetime pension and international prestige. His unusual philanthropic initiative seemed like the start of a new era for the continent - African entrepreneurs who had built their fortunes rather than stolen them would begin to leverage their wealth to promote better governance.

Then reality smacked Ibrahim in the face: After two successful rounds of awarding the prize, his foundation could not find any qualified candidates in 2009. Ditto, 2010. In 2011, the prize went to Pedro Pires, the outgoing president of tiny Cape Verde, but has come up empty since.

In other words, Africa continues to struggle with an old curse: dictators and other varieties of strongmen who cling to power for decades while hollowing out state treasuries and fledgling government institutions. The leaders of Angola, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, and Zimbabwe, for example, have all held power for more than 30 years. Several leaders have occupied power for well over a decade, including Western favorites like Rwandan President Paul Kagame, who appear to be positioning themselves for much longer runs.

When Good Things Happen to Bad Leaders

Although the continent seems trapped in the bad old leadership model, Africa's economy is booming, growing at rates that put the region on par with Asia. And despite a few headline-stealing crises - such as the recent terrorist attack on a Kenyan mall by members of the Somalia-based group al Shabaab, or the ongoing attacks by Islamic extremists in Nigeria - Africa is arguably more stable and democratic now than it has ever been. But the good economic news belies the fact that the continent is still in need of good leadership.

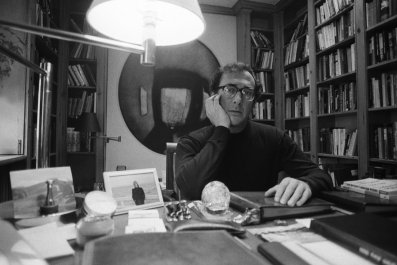

At 67 years old, Ibrahim is fiercely proud of his identity as a Sudanese and as an African, and he manages to be self-effacing while still exuding the confidence of a self-made billionaire. As an engineer specializing in radio technologies, he earned his Ph.D. at the University of Birmingham, England, in 1981, then did pioneering work on how radio signals move through the environment. Two years later, he was hired by British Telecom, where he led a group that designed the world's first handheld mobile phone network. He then formed his own consulting company, Mobile Systems International, which won lucrative contracts from companies like Siemens and Motorola. From this success, in 1998 Ibrahim went on to found Celtel, a mobile phone provider in Africa. After Ibrahim sold the company in 2005 to a Kuwaiti firm, Forbes estimated his personal fortune at more than $2 billion.

The award he founded has won him admirers, but the way the prize has stalled reveals a paradox. "If the issue is bad leaders who have stayed in power too long, but you are giving a prize to leaders who have done a good job, then those two things don't add up," says Calestous Juma, a Kenyan professor of international development at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government. "In an Africa where a good leader may be somewhat rare, you may want a good leader to stay in power longer. On the other hand, I don't think there are bad African leaders out there who are thinking: I am going to leave power after a certain number of years in exchange for a prize. Such people don't exist."

Another maddening wrinkle is that those who ruthlessly cling to power are likely to reject the international norms of democracy upon which the Ibrahim award is based. Recently, a loose coalition of African heads of state lobbied to get the continent-wide political body, the African Union, to push back against the International Criminal Court for a series of crimes-against-humanity indictments it has pursued against African leaders, including Kenya's newly elected president, Uhuru Kenyatta. Some Africa analysts see this as part of a momentous struggle between liberal, reformist ideas that are gradually taking root around the continent, and the rival tradition of strongman-style rule.

This ideological tug-of-war sheds light on the daunting challenge facing the Ibrahim Foundation and suggests that some of its other, less-heralded initiatives may be more successful in promoting political reform.

Ibrahim has been quietly promoting his African governance index, which establishes standardized performance benchmarks. It allows both Africans and outsiders to compare states against each other and gauge their results according to four broad criteria: safety and rule of law, participation and human rights, sustainable economic activity, and human development. By those standards, tiny Mauritius, for example, is doing the best, while Somalia is performing the worst. The system has caught on rapidly: The rankings are widely reported in African media, and African governments appear to be increasingly competitive about the index, complaining when they think they deserve better grades and crowing when they move up the list.

"As an engineer, you don't talk about things. You define them," Ibrahim told The New Yorker in 2011. "We wanted to define governance. And we wanted to find out how to measure it."

What is most remarkable, and ironic, about this is that the criteria of the governance index are based on fairly standard liberal notions of good government - notions that appeal to the very African leaders who might complain about the preachiness of the West (compared to newer economic partners like China). It helps that Ibrahim is African and is thus uniquely positioned to promote an agenda of reform and good governance with little controversy and scant rejection. He and his foundation are very active on Twitter and other social media, but he has been careful to avoid anything that has even a soupcon of preachiness.

Juma hopes Ibrahim's example will encourage a fast-growing new generation of African billionaires to use their money in innovative ways to promote better governance. "Probably the most important impact of Ibrahim's work in the long run," he says, "will be showing the way for others to support good government."

Howard W. French teaches at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, and is the author of the forthcoming China's Second Continent: How a Million Migrants Are Building a New Empire in Africa.