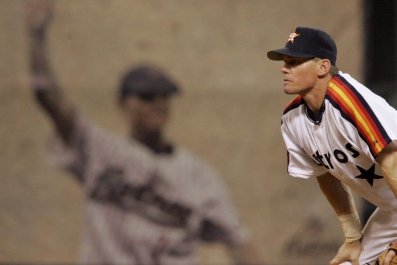

Late last year, Airbnb announced that it's going after the major hotel chains - which at first sounded kind of cute, like a precocious Little League pitcher saying he's going to strike out Miguel Cabrera.

But when CEO Brian Chesky laid out his thinking for me while sitting on a barrel in Airbnb's new, funky headquarters in San Francisco, I thought the investors who have pumped $326 million into the company might not be too dim. Airbnb is becoming much more than a way to spend $26 a night to sleep in London with five other people at The Imperial Fleapit.

In fact, Airbnb is looking like a proof point of a trend that has been getting a lot of attention lately. Some refer to it as the DIY - for do it yourself - movement. Venture capitalist Hemant Taneja, looking at it from a different angle, calls it "unscaling." Chesky uses the term "decentralized production." Marc Andreessen hit on the concept in a manifesto entitled "Why Software Is Eating the World."

It all points to the same idea: Information technology is eroding the power of large-scale mass production. We're instead moving toward a world of massive numbers of small producers offering unique stuff - and of consumers who reject mass-produced stuff. The Internet, software, 3D printing, social networks, cloud computing and other technologies are making this economically feasible - in fact, desirable.

The hotel industry - and the way Airbnb thinks about it - is an example of how that is playing out.

There is a fundamental truth about big hotel chains that is only now being exposed in the Internet age: Hotel chains grew out of a lack of information.

In the middle of last century, cars and highways made the world far more mobile. Many more people traveled to towns they didn't know, and they needed places to sleep. They had no way to know which hotel or boarding house might be nice or offer amenities they wanted. Travel guides, like Mobil's, popped up in the 1950s, but for the most part information remained scarce.

Chains took advantage of that data deficit. If you knew a Holiday Inn in one town, you knew the Holiday Inn in the next town would be roughly the same. The brand's motto played off this: "The best surprise is no surprise." The uniformity and comfort of a chain trumped the risk of an unknown, independent place.

As chains got bigger, they could afford to widely advertise - a way to spread more information about the consistency of their hotels. Independents couldn't keep up. They had limited ways to get information to travelers. As long as this big information gap existed, chains grew and independents struggled. The gap drove chains to offer uniform accommodations at scale - and we got today's hospitality industry, dominated by the likes of Hilton, Marriott and Starwood.

Chesky got to thinking about this when his late grandfather told him Airbnb reminded him of his childhood, when his family would arrive in towns and stay at boarding houses. Chesky thought: If the Internet was around back then, would hotel chains as we know them have been created? "And the answer is absolutely not," Chesky says. "I'm not saying there wouldn't be hotels, but they wouldn't look like they do today."

The Internet is proving that by closing the information gap. It started with sites like TripAdvisor, but Airbnb takes it to another level by helping any individual with an extra room to rent share that information with a vast number of travelers. If the information is good - if Airbnb, for instance, can eliminate the downside of surprise - the hotel chains' competitive advantage of uniformity will become a disadvantage. In the DIY era, many more travelers will gravitate to unique places to stay instead of opting for the vanilla sameness of a Holiday Inn.

This is not a bombshell for the major chains. Marriott and others are working furiously to build boutique hotels because they see the eventual fate of cookie-cutter hotels. The chains may adjust to this new era, and Airbnb may yet blow it. The site has more than 500,000 rooms, which means it now offers as many rooms as the biggest hotel chains. But Airbnb is still working on the essential element of eliminating surprise. Its critics say there are still too many instances of an Airbnb rental failing to live up to its photos and description.

Still, the underlying story of Airbnb, information and the major hotels will get replayed in lots of industries in the next few years. Mass production and sameness mean safety when information, intimacy and trust don't exist. As information, delivered globally and cheaply over the Internet, brings back intimacy and trust, the advantage of uniformity at scale slips away.

"These new economies of unscale will be good for job growth, because they open up thousands of new market niches for exploitation," Taneja wrote in Harvard Business Review. "To succeed, though, first we have to unlearn what we have been taught about business. We have to think in an unscaled mind-set, where the emphasis is on a greater number of specialized products sold to customers who know exactly what they need."

That notion isn't lost on Chesky. "In the last 15 years, bits and bytes have been revolutionized," he notes. "The next 15 years, I think you will see things, atoms, physical industry, services - things in the real world - starting to be changed. All that stuff will change."

If Airbnb can ride that wave, it will end up in the major leagues.