If you're not famous, do you belong in a Hall of Fame?

This week the Baseball Writers Association of America (BBWAA), an aggregation of otherwise literate humans who cannot correctly compose their own acronym, submitted their annual ballots for selection into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Three retired players - former Atlanta Braves pitchers Greg Maddux and Tom Glavine and former Chicago White Sox slugger Frank Thomas - received the requisite minimum by appearing on 75 percent of the 571 ballots.

Three up, three down. However, no one from that trio of inductees will garner more attention this week than Craig Biggio, who was snubbed in the voting process. Or was he?

A seven time All-Star who spent all of his 20 seasons with the Houston Astros, Biggio's name appeared on 74.8 percent of the ballots - robbed-at-the-wall power as far as Baseball Hall of Fame voting goes. Because Biggio came so close - he needed just two more votes - and because so many scribes voted for him - nearly 75 percent - you can bet that nearly three out of every four writers, but not exactly three of every four, and certainly not more than three of every four, will opine either in print or on Twitter that the former catcher and second baseman deserves to be in the hall.

Which is like saying that every fly ball that strikes the outfield wall deserves to be a home run.

Biggio was an outstanding player in some respects: Only 20 men have collected more hits than his 3,060 - and yet his .281 career batting average puts him in the same company with Darby O'Brien and Ducky Holmes. Nearly 600 former players have higher career batting averages. Few fans outside of Houston and maybe the New York metropolitan area, where Biggio grew up and played collegiately, ever circled a game on the schedule because Craig Biggio was playing in it. He could very well enter the Baseball Hall of Fame, through the front door, with a tour group, without anyone recognizing him.

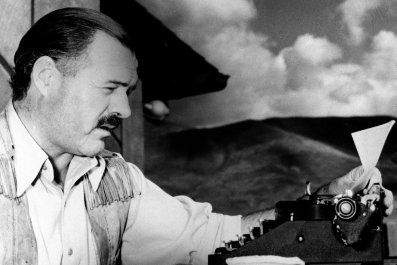

The problem is not that the hall is too exclusive; it is that the hall is not exclusive enough. In 1936, via the same balloting process in place today, five men were selected to the inaugural Hall class: Ty Cobb, Walter Johnson, Christy Mathewson, Babe Ruth and Honus Wagner. None of them, not even Babe Ruth, was a unanimous choice, indisputable proof that trolling predated the existence of the Internet by at least half a century. In fact, no one since has ever been voted into the hall unanimously.

And while the omission of Ruth on anyone's ballot in 1936 was as obtuse as the omission of Mariano Rivera will be when he becomes eligible in 2019, expanding the strike zone here is a more egregious error. Currently, each BBWAA member is permitted to jot down the names of 10 players on a ballot, or one more than Los Angeles Dodger skipper Don Mattingly is allowed when filling out a lineup card. And there is talk of expanding that number.

It would be just the latest example of an insidious trend prevalent in sport and other sectors: Inclusivity Creep.

At some undefined point in American history, but almost certainly after the incursion of "Up with People" at Super Bowl halftime shows, it became incumbent upon us as a populace to cast wider nets for glorification. And thus, whereas 48 teams earned invites to the NCAA men's basketball tournament in 1982, now 68 do. Syracuse coach Jim Boeheim is an avowed proponent of a 128-team field because that many more coaches will be able to say that they led their teams to the Big Dance.

Ten teams qualified for the NFL playoffs in 1988; now 12 do. And soon, if commissioner Roger Goodell has his way (and when does he not?), 14 will. College football is moving from a national championship game to a four-team playoff next year and, if its proponents have their way, an eight-team playoff will follow.

The Oscars had five best picture nominees from 1944 through 2008. Now they have 10, which by my math reduces the luster of that category by exactly half. Which the major studios hope you will fail to ascertain when deciding between watching "an Oscar-nominated film" or NetFlixing season three of Justified.

It's like this: If everyone is wearing Members Only jackets, what exactly are you a member of?

Perhaps they should call it the Hall of Legends and reduce the roster in the Baseball Hall of Fame by half. We know who baseball's legends are. They're surnames: Cobb, Speaker, DiMaggio, Feller, Koufax, Gibson, Rose (yes, Rose), Maddux. They're nicknames: Babe, the Iron Horse, Teddy Ballgame, Hammerin' Hank, the Say Hey Kid, the Big Hurt.

Tom Glavine? Really?

My litmus test is simple: Would that player's addition to a sports hall of fame more enhance the hall's reputation or would it more enhance the player's? It should always be the former.

"It's the hard that makes it great," a manager named Jimmy Dugan (Tom Hanks) once said, and he was specifically talking baseball. But Dugan might as well have been discussing the Navy SEALs or Rhodes Scholars or the Baseball Hall of Fame. What everyone who merits, truly merits, inclusion in any of those bodies should have in common is not a 75 percent-or-better approval rating. What they should have in common is the knowledge, forged by deeds, that they are, without question... in a league of their own.