With the Dow registering an all-time high and the stock market crash of the fall of 2008 fast retreating in the rearview mirror, a new normal has descended on Wall Street. As business perks up a fresh spring is in the step of bankers and those working in the financial sector that hasn't been seen for a long while.

The deep wounds of the hard times of 2008 and 2009 appear to have healed. Optimism is in the air. After Twitter's successful IPO, others in the tech sector - such as Spotify, Dropbox, Snapchat, Pinterest, and Scribd - are lining up to raise cash for further expansion, and there is a long line of buyers.

Hedge funds are riding this optimistic wave. Daniel Loeb, the latest financial titan to make the headlines, has been on a spending spree, snapping up large parts of FedEx, Sotheby's, Google, and Coca-Cola. On Broad Street, the bull is on the rampage once again, and all is right with the world.

But wait. Quietly and with hardly a whimper, a growing number of Wall Street types in their 30s and 40s say they are suffering. Not from a shortage of money, though they are known to grouse that bonuses are not what they used to be, and some of the top salaries, too, have been trimmed.

No, it is not their wealth but their health that is giving out. While their jobs could hardly be compared to those of police officers or firefighters, increasingly they are saying that every day they sit at their desks, gazing into their number-laden screens, they are taking their life in their hands.

Once they could shrug off the effects of all the stress - it came with the territory. But many of them have started to notice some of their old friends and colleagues are missing. Their jobs either drove them away - or drove them to an early grave. And many are asking, "Who will be next?"

For those who work outside the Financial District, such problems are hard to take seriously. As corporate profits soar, so do salaries.

While nationwide the gap between the rich and poor is expanding by the minute, and 11 million Americans are still looking for work of any kind, a typical worker in New York's financial sector can expect to haul in $180,000 a year.

And that is just an average. The sky is the limit for those at the top. For instance, the median income for a corporate lawyer is $1.6 million.

So what's all the fuss about?

It was not in the bowels of Wall Street, but in the sparkling waters off Pacifica Beach that one self-described "recovering financial services entrepreneur" found himself fighting for his life on what was meant to be a relaxing day of surfing.

"I had a full-blown heart attack," the 39-year-old said. "Stress is a f***er."

The heart attack, however, was secondary to the fact that this longtime Californian almost didn't make it to shore alive. "I nearly drowned," he said, asking to remain unnamed, as he is still recovering (and looking to avoid any further stress). "I could still swim, but it hurt like hell."

Tall, fit, and athletic, he had never imagined he had a heart condition. He did not have a family history, did not smoke, ate lean foods, and rarely drank alcohol. Yet stress, over time, had caused plaque to build up in his arteries. When a big, cold wave hit him on his surfboard in September, his coronary artery ruptured.

The incident is not an isolated one. Just this month, Kimberly Mounts, the rising-star New York hedge fund manager from Goldman Sachs, died shortly after suffering a heart attack after nothing more than a trip to the gym. A nonsmoking, vegetarian teetotaler, Mounts "worked out religiously," according to her brother. She was just 48.

"No one wants to talk about it, but we're going to be hearing more and more about this," said Heidi Hanna, a San Diego-based expert on brain health, resiliency and energy management. "The ones who are really surprised by this are the ones who don't smoke, [who] eat well, and [who] exercise regularly. But many of them tend to overexercise. They're very stressed, they aren't getting enough sleep, and have a little bit too much to drink."

Hanna said she's hearing from CEOs about an increase in heart problems, strokes, and nervous conditions, ranging from the dry heaves to full-blown panic attacks.

"I have executives telling me they're having trouble getting out of bed in the morning," she said. "To me, a stressaholic is someone who is dependent on stress and stimulation for their energy. That is how a lot of people get by. They are addicted to adrenaline. You can literally measure it in the chemicals of the brain."

If you look at the numbers, it's all there: a raft of new data showing that people in their mid-20s to mid-40s are starting to exhibit signs of extreme battle fatigue from the financial crisis stemming from extreme stress - not just in their sagging wallets, but in their flagging health.

Life-threatening cardiovascular events, such as heart attacks, have leapt to scary new highs among young professionals, while strokes in people under 45 have spiked, not just nationally, but on a global scale. The main triggers, researchers agree, include crushing stress, crippling financial worries, and prolonged, widespread job instability, all of which are proven to directly impact health.

These factors appear to be clustered at the very top of the food chain, where job insecurity is at its worst, said Michael Goodman, managing partner of Long Ridge Partners, a Madison Avenue executive search firm. "The turnover is far greater than it ever was," he said. "If you're not a principal or a founder of an organization, the average time you'll keep your job is 24 to 36 months. You used to be able work at a bank forever and never get fired. That's not the case anymore. You constantly have to justify your position, prove your worth. Your seat is no longer guaranteed."

Not so these days with the general population, which is finally starting to enjoy some job security. By contrast, those who remain in the Wall Street shark tank are doing battle over a shrinking job pool in what is shaping up to be a game of musical chairs.

The health data could not be clearer on the damage caused by ongoing exposure to job stress. "Studies have shown that chronic or repeated exposure to ... unstable labor market status might be more harmful to health than exposure to job insecurity at one time point only," said the largest-ever study on the subject, published in London in August. It examined the link between job insecurity and heart disease, bringing together data from more than 170,000 professionals in America and Europe.

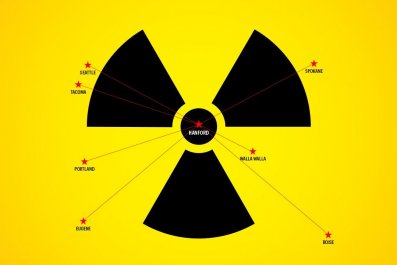

Since peaking ahead of the 2007 downturn, more than 5 million jobs in the financial activities sector of the economy have disappeared, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. This has led to a sharp rise in instability among high-ranking professionals, which, in turn, is causing poor health.

The biggest factor in this rash of health issues among young executives may be the most overlooked: Many who entered the job market in the mid-1990s were swept into an intoxicating, decade-long whirlwind of promise and wealth that saw them living lush lives far beyond their wildest expectations.

For them, there was some striving, but results came fast. For many on Wall Street, wealth came easily and, for a time, seemed almost effortless. Many thought they would be set for life. It wasn't until the crash that reality abruptly kicked in.

"They're not living in reality in a sense, so when the fall comes, it comes hard," said Christopher Bayer, who runs the Wall Street Counseling Center in New York. "I work with people who make $10 million and $20 million a year, and if they lose a job [paying that much] and realize they may never make that much again, they have to come to terms with that.

"Their expectations and their sense of entitlement is so great, they cannot bear an inferior position. They are extremely capable and bright, but they suffer from emptiness and fall into depression, substance abuse. They fail to understand what it truly means to be a soulful person. That is my job, to show them the wealth within."

Like the Greek myth of Icarus, these young executives were given wings to fly, which, as they rose to the highest echelons, melted in the heat and sent them tumbling. After getting a taste of the good life - and having it snatched away - these professionals, many of whom were not in high enough positions be responsible for the financial crisis that pulled the rug from under them, have been dispossessed and are starting to suffer prematurely from life-threatening diseases.

"It is one thing to struggle and make it, [another] to struggle and never achieve your dreams," said a New York-based executive who lost his hedge fund in the run-up to 2008. "But to struggle, achieve your dreams, really get somewhere, and have it taken away is very painful. Yet we're not very sympathetic creatures, are we?

"I'll bet a majority of the comments for this story will be from people thrilled to hear that we're suffering. Who's going to feel sorry for the guy who's stressed out and makes half a million dollars a year?"

The data show that not only that health problems have proliferated in the 40s-and-under crowd since the credit crisis took hold in 2008, but strokes shot higher on a global scale - and kept on rising - during the period the market embarked on its perilous swing from high to low. While the data do not concentrate on the highest-earning professionals, they repeatedly highlight factors behind why so many on Wall Street are having major health issues at a young age.

A study from the American Neurological Association indicates strokes in people under 45 climbed in almost all age and gender groups between 1995 and 2008, the year the market began its precipitous slide. Men in their 20s and early 30s were particularly prone to health fallout, with stroke hospitalizations rising nearly 15 percent.

The study caused a stir among doctors because, until then, incidence of stroke appeared to be stable or decreasing. The study observed the rates and risk factors for stroke appear to be heading higher among young adults, compared with a decrease in older adults, warning: "Our results from national surveillance data accentuate the need for public health initiatives to reduce risk factors for stroke."

Meanwhile, the health data emerging from financial-crisis hot spots are proving compelling - some of the first data of its kind, said Catherine Stoney, of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md.

"It's a new field of study, how these financial crises might impact people's health," she said. "In the past, we've seen increases in heart attacks after natural disasters, such as after Hurricane Katrina." But measuring how man-made, disasters can hurt people's health "is not a very well-developed area," she said.

This June, a team of cardiologists in Greece - a nation rocked by the biggest default scare of the global financial crisis - crossed the Rubicon, releasing what it described as "alarming" findings pinpointing "the potential association between the financial crisis period and acute myocardial infarction" - what the rest of us call heart attacks.

During the most stressful time of the Greek debt crisis, from January 2008 to December 2012, the department of cardiology at the General Hospital of Messinia in southwestern Greece measured heart attack rates across a region of 170,000 people. Heart attacks requiring a hospital stay in that period leapt roughly 44 percent, compared with the previous five-year period. There was also a significant rise in cardiac events among men, in particular those aged between 20 and 44.

Noting that Argentina's catastrophic default just over a decade ago appeared to dramatically increase the risk of death by heart attack, the Greek study called for further data collection and analysis of how high unemployment rates and financial turmoil might lead to cardiovascular events. "The implications of these findings are particularly important for policy makers and health authorities," it said.

Stoney agrees. "The fact that strokes have increased worldwide and they've increased in this country is of particular interest, but we still do not fully understand the reasons for it," she said. On average, men tend to suffer heart attacks about 10 years earlier than women, although a heart attack in anyone under 50 is considered highly unusual.

"There are data from both nonhuman primates and humans showing that chronic stress is associated with about a 40 percent increase in the occurrence of coronary heart disease and coronary events," she adds.

Without rest and relief after exposure to prolonged stress, the body starts to break down. Plaque begins to form inside the blood vessels of the heart. Rising blood pressure, increased inflammation, reduced circulation and the release of hormones, such as cortisol and adrenaline, can lead to crises even in the most healthy.

"I had no idea I had a serious heart condition," the surfing financial-products engineer said. "I have plaque buildup in my arteries. Too much excitement, and my head might explode."

While no specific health data on the 1 percent exist, it is widely acknowledged among doctors that, in addition to unemployment and financial fallout, what is proven to cause stress is pretty much everything that makes people in high-ranking jobs extremely productive: long hours, multitasking, 24-hour use of technology and relying on short-term fixes for energy like exercise and caffeine without taking the time to eat, sleep, or break properly throughout the day.

"We are caught between our ego and reality," the financial products engineer said. "We must change, but we don't want to, hence the conflict. Basically, our egos have written checks our bodies can't cash."

In other words, the same thing that makes these executives successful may be the thing that's killing them. "It's interesting, because many of the risk factors that pertain to heart attacks also pertain to strokes," Stoney points out. This has not been helped by high rates of divorce among the moneyed crowd, which edged even higher during the financial crisis, particularly in states like Connecticut, known for its big-ticket divorces, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

High levels of stress cause sleep disruption and shorter sleep duration, also a significant risk factor for obesity. This enhances the risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and sleep apnea. "This sleep issue is a big deal in executive circles," Hanna said.

"This is a place where if you're stressed or tired, instead of just taking a break or getting rest, you push harder. Telling these people to take a break is the worst thing you can say to them. They don't want to take a break. They want to be told what to do."

One reason top executives may be particularly vulnerable to life-threatening diseases at young ages, especially during times of economic upheaval, may stem from their intense sensitivity to hierarchies - and where they stand in them.

"In cynomolgus monkeys, which have a very hierarchical social structure that is determined by the monkeys themselves, disturbing the hierarchy is one of the most stressful things you can do," Stoney said. "One study shows that monkeys who had to go through this once every two months for more than a year had more clogging and plaque in their arteries than those who did not," leading to greater risk of cardiac events. In humans, additional studies show how individuals reporting long-term stress at work and home, including financial stress, have double the risk of a heart attack, she said.

Money is what people stress about the most, Kirsch said, and "rich, successful people who are used to having their lives firmly under control" can be some of the biggest sissies when things start to break down.

Dialing it down isn't easy, said one 38-year-old Wall Street hedge fund executive who woke up in his hotel room with a searing pain in his chest last summer. "I was screaming," he said. "My eyes felt like someone was boring holes into them. It felt like something was drilling my ears and my teeth. The skin on my face was bubbling up like I had anthrax. It was unreal. Even now, I am still healing." His affliction: a rare nerve attack, brought on solely by stress. (He asked to remain anonymous.)

Like the financial-products engineer, he'd been through his own job upheaval in the past five years and it caused far more stress than he'd realized.

"The hospital's head of neurology was shocked after seeing my tests, because I had no obvious health issues. He asked: 'What wrong with you. Are you unhappy? Are you stressed out?' I said, 'No, I'm fine. Yes, I pace the floor at 5 a.m., thinking about my future and my career and why I'm not yet a CEO. But I went to Harvard Business School. That's normal.' The head of neurology looked at me like I was crazy and said, 'No it isn't.' "

The hedge fund executive said at first he felt self-conscious about seeing a psychiatrist to discuss his stress, but eventually he opened up to other friends on Wall Street about his experience. He was surprised to learn how many of them had had similar issues.

"It is like a swingers club," he said. "No one talks about it unless you express an interest. Once you do, they all start coming out of the woodwork."

What he found most startling was that those he considered to be the types who would never need a psychiatrist or spiritual guru actually swore by them.

"I found that people at the very top of their game have this all on lockdown. That's why they're at the top of their game. They're like, 'What do you need? Here's my psychiatrist, my psychic, my yogi master. And I got Tony Robbins on direct dial.' "