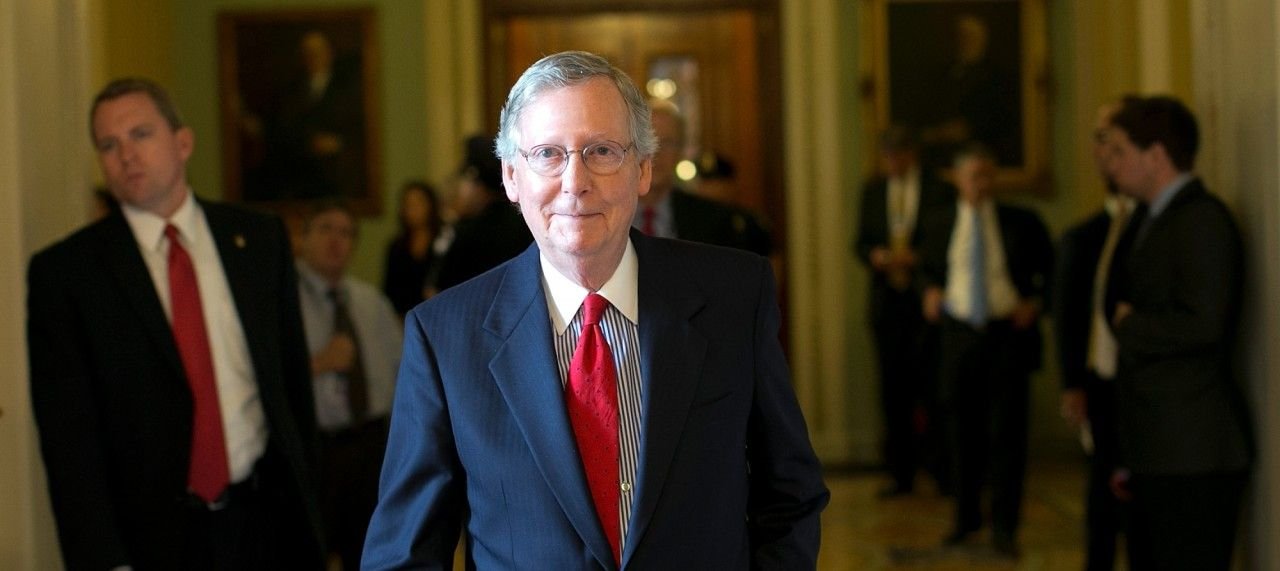

When the rollout of President Obama's Affordable Care Act turned disastrous, Senator Mitch McConnell, Republican leader in the Senate, might be excused for suspecting divine intervention. Fighting for his political life - and the Senate seat he has held for 28 years - against Democratic challenger Alison Lundergan Grimes, currently Kentucky's secretary of state, the embattled McConnell set to work using Obamacare to attack his opposition.

"Anything short of full repeal leaves us with this monstrosity," McConnell said at a press conference in Kentucky last week. "The question you should be asking [Grimes] is, are you for or against getting rid of it?"

McConnell is one of many Republicans hoping to win in red states next year by campaigning against the troubled health care law. But it may not be the killer issue he hopes it is: In Kentucky, of all places, Obamacare is going remarkably well.

"Most people don't sign up for something until the deadline," said Jonathan Miller, a Democrat and former Kentucky state treasurer. "If that is true in Kentucky, then the positive success the program has been having is only the tip of the iceberg."

More Kentuckians have applied for coverage through the state's exchange, called Kynect, than in almost any other state, and Kynect has nearly twice as many completed applications as glitch-filled, federally run HealthCare.gov. As of November 14, 380,000 people conducted preliminary screenings to discover what coverage they are eligible for; 39,186 have enrolled in Medicaid; and 8,780 have selected a private insurance plan.

Last week, the Department of Health and Human Services singled out Kentucky as an example of how to make the law work, highlighting "nearly $6.5 million in contracts to navigator programs throughout the state to ensure that Kentuckians have assisters to help them determine their health plan needs and assist them in choosing appropriate plans." Health care advocates in the state point to Kynect's carefully crafted website kynect.ky.gov to explain Kentucky's impressive numbers.

For the success of its affordable health care campaign, Kentuckians can thank second-term Democratic Governor Steve Beshear, most of whose ambitious plans have been thwarted by Republicans in the state legislature. With one in six Kentuckians uninsured, Beshear saw health care reform as the place he could make his mark. He bypassed the legislature to become the only southern state to expand Medicaid and implement a state-run insurance exchange. Then he set about making sure the law worked.

"He's a lame duck, and he's term-limited," said Republican Trey Grayson, a former Kentucky secretary of state. "This could be his legacy."

Beshear, who tried unsuccessfully to unseat McConnell in 1996, may be helping Grimes as well as the uninsured. "Kentucky's exchange has been a model of success for the nation," said Representative John Yarmuth, the lone Democrat in Kentucky's congressional delegation. "As more Kentuckians receive coverage, opponents' attacks of the law will ring hollow."

"I think that ultimately this could really backfire on McConnell," said Miller. "The fact that he's using so much time and energy to tie her to [Obamacare] could ultimately be a waste of resources."

McConnell's situation mirrors a predicament that former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney faced during his failed 2012 presidential bid, when the central message of his campaign - a flailing "Obama economy" - began to conflict with improving economic forecasts. As unemployment dropped in key swing states like Ohio and Florida, Republican state governors began to tout economic progress, undermining Romney's argument that the president didn't know how to fix the economy. Romney's message was further eroded when unemployment fell below 8 percent - a symbolically important number - just one month before the election.

"It's a little jarring when you see a governor talk about how great [Obamacare] is and a senator talking about how terrible it is," Grayson said.

Still, Grayson, who campaigned against the Affordable Care Act during a 2010 Senate bid in Kentucky (he lost to Senator Rand Paul) believes McConnell is right to go after Obamacare now, presenting himself as a stalwart opponent to an unpopular law. Also facing a primary challenger from the right, McConnell seems to have little wiggle room on the issue. And since neither Obama nor Obamacare is popular in Kentucky - a state that backed Romney by 23 points over the president last year - strategists see McConnell's attempt to tie Grimes to the two as the right tactic.

What is unclear is whether the law's success in Kentucky will ultimately neutralize that line of attack. The jury is still out on whether voters will be more influenced by seeing their friends and family get access to affordable health care, or by reports of plan cancellations, rising premiums, and the stigma of Obama's name in a deep red state. In Kentucky, the Medicaid expansion alone is expected to reduce the number of poor people without insurance by nearly 60 percent, a good test of whether successful implementation of Obamacare nationwide could boost the law's popularity and help Democrats get elected.

For her part, Grimes has been cautious about embracing the new law, but Miller sees an opening for her to exploit its success in Kentucky in the coming months.

McConnell will try nationalize the race, tying Grimes to Obama and the reputation of the health care law nationally, Miller said. For Grimes to win, "this has to be about Kentucky vs. D.C., and she can use Obamacare as a way to say, 'Things are better in Kentucky than in D.C., and I want to take that Kentucky attitude to D.C., against the guy that is the ultimate symbol of what's wrong with D.C.' I think that's where she has a very potent message."