Amadou Janneh knows firsthand the price of resistance in the Gambia. He was in prison in September last year when nine prisoners were dragged from the cells around him and taken to the firing squad. None had more than a moment's warning that they were to be shot dead. "At around 9:30 p.m., they just came in and selected nine," Janneh says. "It was somewhat random. No witnesses, nothing."

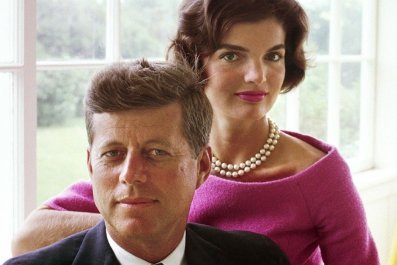

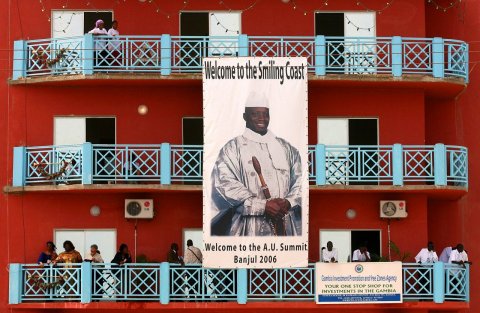

It was the end of the Muslim holy month of Ramadan, and religious leaders had been petitioning Gambia's unpredictable president, Yahya Jammeh, to address appalling conditions in the prisons and pardon political prisoners. Instead of offering clemency, though, Jammeh declared that the backlog of inmates on death row would be cleared within a month. The executions began five days later.

Jammeh is an archetype of the crazed African dictator rife on the continent in the 1980s. He threatens to behead homosexuals and claims to be able to cure AIDS using medicinal herbs, all the while violently suppressing dissent. His regime, like others in the region, has created a society that is oppressed and disenfranchised, closely mirroring the conditions that drove popular revolutions across the Middle East and North Africa. But years on from the start of the Arab Spring, sub-Saharan activists are still waiting for the revolutionary spark to catch.

Janneh, a former information minister, was in prison for what the government deemed a serious crime. He was arrested in June 2011 along with three accomplices and found in possession of items threatening to the security of the country: T-shirts. Each of the 100 weapons bore the slogan "End Dictatorship Now." Placed in solitary confinement in the maximum-security Mile Two prison, his trial lasted seven months, after which he was handed a life sentence. He knows what his detention was supposed to achieve.

"I was arrested when the Arab Spring was in full swing," he says. "They wanted to make sure that this sentence served as a deterrent." Likewise, the executions. "Sending me to prison for life was not enough. They saw problems in neighboring countries and thought maybe they would send a final signal to any potential rivals: This will be the fate that awaits you."

Janneh was fortunate - he holds a U.S. passport, and an American campaign, fronted by the Reverend Jesse Jackson, secured his release into exile not long after the executions.

He remains defiant, pointing out that activists are making sure the news gets out, and more importantly, gets in. "I think we are almost at that tipping point, because the degree of repression has increased substantially. The people are getting very frustrated," he says. "There may not have been an Arab Spring in the Gambia, but now the message they were trying to contain, the message that they are a dictatorship, has mushroomed. Now you have all sorts of organizations and individuals referring to the Gambia as a dictatorship. There's a great deal more spotlight on the regime than before.

"Unless groups like mine are successful in their nonviolent campaigns, we see the possibility in the very near future of violent upheaval in the country. The system as it is now is unsustainable.

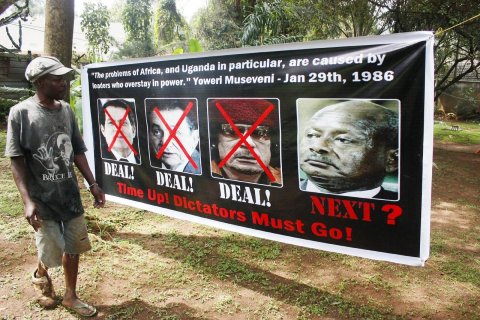

In the cold light of winter, the Arab Spring may seem to have merely replaced one set of dictatorships with another, but for many activists in sub-Saharan Africa it remains a beacon. Activists in Eritrea, Ethiopia, Uganda and the Gambia all refer to Tunisia's Jasmine Revolution. It was a unifying shout in the dark for change. Whether the revolution is coming here, though, is far from certain.

Africa has grown up in the past two decades. In most of the continent, the bad old days of dictatorships and persistent conflict are over. The overwhelmingly negative image of the continent, one fed by charity appeals and sepia-tinged coverage of war zones, has given way to one of economic growth and opportunity. In terms of absolute gross domestic product growth, sub-Saharan Africa has been booming for 10 years, with many countries posting double-digit rises on the back of high commodity prices, debt relief, improved political stability, and an excess of hot money flowing in from the West and from rising economic powers in Asia and Latin America.

The apparently insoluble crises in Central Africa and the Horn remain, and new fronts may have opened up in the Sahel, but there are far more economic success stories in Africa now than there are basket cases. Conflict-ridden countries from the 1990s are now fronted by well-educated economists and academics rather than uniformed despots.

However, pockets of absolute repression remain. The Gambia is one, and dissent can be fatal in Angola, Eritrea, and Ethiopia. Elsewhere in countries that appear progressive in their economies, human rights are in stasis; press freedoms are curtailed; and votes are won by intimidation, patronage, or fraud. De facto single-party systems control Nigeria, Rwanda, Uganda, Tanzania, and South Africa; and while their brutality or dictatorial tendencies may differ wildly, the absence of true accountability of leaders has led to imbalances in power, wealth and opportunity.

Economic growth has masked a stalling in the spread of democratization and freedom. In many cases, that growth has not delivered prosperity for individual citizens but has been captured by elites. In too many African nations, there is little incentive to deepen and broaden the economy. Corruption has become entrenched and has blocked access to economic opportunities. Governments can act with impunity, ignoring their constitutional term limits while shamelessly accumulating wealth.

In the 48 countries of sub-Saharan Africa, 20 leaders have ruled for more than 20 years. The average time in power is 17 years - and that includes some newcomers elected only in the past 12 months. It does not include the quasi-democratic dynastic succession in Gabon, where the election after the death of Omar Bongo was won by his son almost unchallenged. "It's very simple: Staying in power in sub-Saharan Africa these days is much more lucrative than ever before," says Vukasin Petrovic, who runs the Africa programs at the Freedom House watchdog, which has been warning of backsliding in human rights on the continent. "Everything that we are seeing in terms of attacks on fundamental freedoms from ruling political elites - closure of operating spaces for civil society and political parity, attacks on journalists - is the consequence of the determination of political elites to stay in power.

"What we are actually seeing is authoritarian solidarity," Petrovic says. "There is no regional pressure on badly performing governments."

A week before Eritrea's independence day celebrations in 2012, phones started ringing around the country. Picking up, Eritreans heard a recorded voice tell them to stay home, to empty the streets that Friday in protest against their government. In a country that bans opposition newspapers and blocks Internet access, that robocall was a message of solidarity for a population cowed by the state and a warning to the regime of Isaias Afwerki, who has ruled the country since 1993.

Behind the messages was the Eritrean Youth Solidarity for Change (EYSC) movement, a group of diaspora activists. Inspired by Egypt's youth movements, they had been searching for a creative way to get information through the regime's firewalls. "We can't use the Internet; people can't access it," Miriam September, a leading activist at the EYSC, says. "And then the idea came: Let's call. Let's call families, friends."

Activists in California set up calling circles, and Eritreans volunteered through Facebook groups to call random numbers. "But we could only reach around 1,000 people in a week or two," September says. "And then someone had an idea to use robocalls. You can make 10,000 calls. It costs you about $3,000."

Like many other leaders of his generation, Afwerki was a freedom fighter, leading the Eritrean Peoples' Liberation Front to victory in their struggle for independence from Ethiopia. After that victory, the unassailable leader of the People's Front for Democracy and Justice has delivered neither. Instead, he created and ruthlessly enforced a single-party system, dragged the country into a bloody border war with Ethiopia and made sure that the country's meagre financial resources remain concentrated in the upper echelons of power.

In an official U.S. communiqué released by Wikileaks in 2010, the American ambassador to the country warned that the regime was "one bullet away from implosion." It was hardly a controversial opinion. "Cruel and defiant" was the most flattering description of Afwerki in the cable, which referred to the president as an "unhinged dictator."

Potential threats to Afwerki's power have been dealt with swiftly. Political opposition comes with a risk of arbitrary detention. Journalists are routinely arrested. Amnesty International believes that as many as 10,000 political prisoners crowd Eritrean jails.

The powerful Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church has been targeted. In 2007, its patriarch, Abune Antonios, was forcibly removed and replaced with a more government-friendly figurehead. Antonios remains under house arrest. On almost every measure - democratic and religious freedom, freedom of the press and of speech - Eritrea is gripped by a brutal dictatorship. Its distress can be measured in the stream of people making the perilous journey across the Sahara and crowding onto small boats to cross the Mediterranean.

A Mauritian human rights lawyer, Keetharuth, who is denied access to Eritrea, has been working on this issue for the past year, interviewing exiles and those connected with the regime. The situation in the country is extremely bleak. People trying to leave the country can be shot. Journalists and opposition leaders disappear.

Events of the past year have given activists hope. In January, a group of dissident soldiers entered the television station, housed at the Ministry of Information, to demand the implementation of the country's constitution - stalled since 1993 - and the release of political prisoners. It was a rare and brave act of defiance.

That abortive coup changed people's perspectives, at home and in the diaspora, September says. All of a sudden, resistance looked possible. There are, she insists, people organized inside Eritrea.

The past few months have seen street fights in Asmara for the first time in a decade, as youth clash with security forces. The regime has reportedly brought in mercenaries to guard its inner circle, as its trust in its own army drains away. "They are slowly, but visibly turning around in front of our eyes." September says. "People are losing their fear."

International pressure can help. In 2011, the Malawian president Bingu wa Mutharika, a leader once feted by the international community for his forward-thinking views on agricultural development, struggled to account for where the money in his budget was being spent. Donors cut aid, which in turn severely limited the government's ability to mask its economic failings.

The Mutharika government cracked down on dissent, harassing opposition figures, academics and journalists. A lecturer was fired from the University of Malawi under pressure from the minister of education - the president's brother - for referring to the Arab Spring in a talk on fuel-subsidy protests.

The resulting organized mass action descended into violence: Soldiers fired on protesters, and 22 people were killed. The protests simmered on, but it was not the people who brought down the president; it was his own treacherous heart. On April 5, 2012, the 78-year-old president died. In a final demonstration of the parlous state he had left his country in, he had to be flown for emergency treatment in South Africa - the hospitals in Lilongwe were out of commission due to a power cut.

In Burkina Faso, pressure is mounting on the president, Blaise Compaoré, amid suggestions that he is trying to extend his term beyond his constitutional mandate. Street protests, opposition challenges and media attention look likely to dampen his ambition.

But these flickers are isolated. At Freedom House, Petrovic is skeptical that a mass movement could take off in the near term because sub-Saharan Africa is yet to develop a large, politically active middle class - another symptom of the resource-led growth that allows the elite to keep much of the wealth.

He adds that the boundless brutality of some regimes is enough to shut down protest. In both Sudan and Zimbabwe, ferocious crackdowns appear to have crushed nascent movements. As George Ayittey, the Ghanaian economist and expert on Africa's political economy, says: "The dictators had learned tricks to put down rebellions."

It is easy to assume that the people of Africa - poor and disenfranchised, denied resources and opportunities - are powerless. History says otherwise.

At the beginning of the Arab Spring, when Tunisians flooded their streets, experts lined up to say that the Jasmine Revolution would never spread; just as the Green Revolution in Iran, or the Cedar Revolution in Lebanon, it would spark and flare but never catch. Within a year dictators had fallen in Egypt and Libya. The demonstration in one small country emboldened the frustrated youth of the whole region.

Governments lock down the Internet, but messages get in and out. The spread of mobile phones, which are fast entering every household, cannot be controlled. And despite the crackdowns, Africa's youth now know what is possible.