Benjamin Franklin once wrote that there are three types of people in this world: "those that are immovable, those that are movable, and those that move." Manal al-Sharif, a 34-year-old computer scientist, is in the process of moving something momentous - the Saudi Arabian cultural taboo of allowing the women to get behind a wheel.

But her activism is in the face of a repressed kingdom. Saudi Arabia is a monarchy and the only country in the world where women are not allowed to drive. Sunni and tribal tradition define the rights of its 20 million women. "People are completely isolated in decision making," she says.

And yet, al-Sharif's protest movement is having more effect than just the future of women drivers. In the same way the frustrations and actions of Mohammed Bouazizi - the Tunisian fruit seller who launched the Jasmine Revolution that paved the way for the rest of the Arab Spring - some see al-Sharif as the catalyst for a much larger change.

"I call it the 'Women's Spring' in Saudi," she says. The al-Saud rulers, she says, are cracking down on dissidents out of fear that the waves from the Arab Spring will spread to the kingdom. But she remains undeterred.

And she is quickly becoming the face of change. Foreign Policy named her one of the Top 100 Global Thinkers of 2011, and her words and actions are spreading throughout the region.

"Manal is no doubt one of world's best examples of people who can move others - even if laws, customs, habits, and powerful governments are opposing her noble attempt," says Srdja Popovic from CANVAS, a Belgrade-based think tank that trains peaceful revolutionaries around the world.

Popovic - who 13 years ago helped overthrow the Serbian dictator Slobodan Milosevic - knows political defiance. His other pupils included the Egyptian April 6 movement, as well as Syrian and Iranian activists. He calls al-Sharif, "one of my heroes."

Women are not technically banned by Saudi law from driving; they are only prevented from obtaining Saudi driver's licenses or using foreign licenses. Because of the ban, Saudi women are largely forced to rely on male relatives or chauffeurs for transportation. Women who try otherwise are usually stopped by police, who call their male guardian.

In 1990, a group of women protested the ban and were so severely punished - by travel bans, detention and slanderous sermons during Friday prayers - that no one tried to challenge the ban again for more than two decades. That is, until Manal al-Sharif decided to get behind a wheel.

Al-Sharif's odyssey - from a young, divorced mother to prominent dissident, a word she had to look up in the dictionary - began in May 2011.

For four years she owned a car she was unable to drive, and she was fed up. She also realized there is no law in Saudi prohibiting women from driving - only constraints of culture and tradition.

A few days later, al-Sharif - in Jackie O sunglasses and a traditional black abaya - got behind the wheel of her Cadillac SUV. A friend in a flamboyant pink abaya filmed al-Sharif with her iPhone.

As she turned on her engine, al-Sharif remembers being "scared and excited."

"I sat down and buckled up ... Then I said, 'Bismillah' [in the name of God], and I drove," she says. "My feeling was that you have a bird... this bird is in this cage his whole life... Then suddenly you open the door, and the bird hesitates: 'Should I leave? Should I stay?' "

Al-Sharif pressed the gas pedal and flew "through the bars."

The women drove through the streets of Khober, in the Eastern Province of the kingdom, for eight minutes. They filmed as they went. A few days later, the religious police detained al-Sharif for six hours, but the video had already received 600,000 hits on YouTube. As the news spread, some women applauded al-Sharif, but others were appalled.

"There are many who don't think what I am doing is good," she says. "They are jealous, or they don't want to change the way they are treated in Saudi society - like queens, or like pearls. Their husbands do everything for them."

Her short drive was a triumph, but it also started a cycle of harassment that continues today. One cleric said to her, "You have just opened the gates of hell on yourself." Another day, she opened an email to find a grim message: "Your grave is waiting."

But al-Sharif was not intimidated. She and other supporters organized a grassroots campaign: designing a logo, alerting local media, and calling for all women to get out and drive on June 17 and to make videos of the trip. The reaction was like a tidal wave.

"The opponents kept telling us, 'There are many wolves in the streets,' " she says. " 'They would rape you, they would harass you, and they would kidnap you if you drive a car.' " Al-Sharif decided she would prove that she would be the one to drive - and not get raped.

She also posted a survey which asked: "Do you want to drive on June 17?" Of the women she polled, 84 percent answered yes. Another question was, "Do you know how to drive?" Only 11 percent answered yes. So she and her campaigners started a driving school using volunteers as teachers.

Empowered, al-Sharif took her cause one step further. She borrowed her brother Mohammed's car and went for a drive, passing a police officer en route.

She went to jail for nine days for "incitement to public disorder," and Mohammed - who told her to "go for it" - was detained by police. When al-Sharif emerged from prison, she found she was the poster child for the right for women to drive in Saudi Arabia.

"I call myself an accidental activist," she says. "I did not even know what the word means." Part of the activism, she said, went much deeper than just getting women to drive.

She grew up in the 1980s and 1990s in Mecca, where the school curriculum dedicates nearly 40 percent to teaching religion. She says she was brainwashed to the moral code of Saudis.

"We were taught we lived in a perfect society. But we were also taught that if we followed rules we went to heaven, and if we did not we would have hellfire."

Her religious education, based on honor and fear, started when she was young. In the seventh grade, without knowing why, she was suddenly forbidden to play with a favorite cousin. He was a boy. They did not meet again for 10 years. She says she mourned not only the lost friendship, but also the implications of separating the sexes.

"I was so upset! We were just playing! We were just kids!" she says. "I was learning that people are controlled by fear."

On holiday in Egypt with her parents and her brother and sister (now a doctor), al-Sharif saw Egyptian women confidently driving, their heads uncovered, their hair flowing. "I just hung my head out the window and stared at them. I could not believe it."

Academic life was her release. Her working-class parents - her father was a truck driver, her mother a housewife - encouraged all three of their children to study. Her mother preferred that the girls did their homework rather than traditional women's work.

"Mom didn't really ask us to do anything around the house," she says. "It was more important for her that we studied." When al-Sharif graduated with high marks, she went into computer science, eventually working for Aramco, a national oil and natural gas company.

But there she saw more injustice: "women being bypassed for promotions and appraisals - just because they are women."

She had her "own awakening" as a Muslim and as a woman watching the disturbing images of the Twin Towers burning on September 11. People were hurling themselves out of windows in an attempt to save their lives. Al-Sharif watched, horrified. "These men [who did that] were not heroes, but killers" she says.

Sent for a year by Aramco to Boston, she had another eye-opener. She rented her own apartment, drove her own car, and no longer needed her father's signature to travel. Returning to Saudi was a painful lesson.

"I had to go to my father to sign papers for me to do anything," she says. "I could not pick up my son from school." Having lived and experienced freedom outside the kingdom, she realized she could not go back to living with injustice.

She devoted herself to more activist causes inside Saudi, but in May 2012 Aramco finally managed to push her out of her job.

"There are two faces to this country," she says. "It's a hypocritical society. Educated men travel outside Saudi, and they see women driving, women with uncovered heads. They think it's fine. Then they get back here, and their views are different."

On October 26, al-Sharif and other activists urged all Saudi women to stand up and take their destiny in their own hands, and drive. The result was that hundreds of women got out in the streets and drove, and 16,000 signed a petition that demands the government lift the ban or, at minimum, give a "valid and legal justification" for the prohibition.

It was a personal triumph. And last year, al-Sharif remarried a Brazilian man, Raphael, whom she met at Aramco. Even that - a private decision - was not easy. She had to get permission from the Ministry of Interior to marry a foreigner - and was refused. She married outside Saudi, but her ex-husband won't let her son travel outside the kingdom. So to see him, she commutes between Saudi and Dubai, where she found a new job.

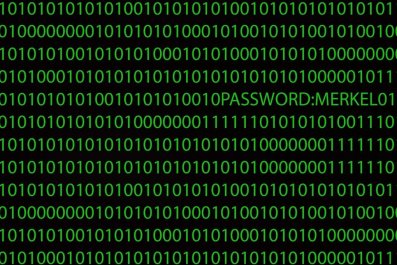

Still, her travel is monitored, and she is on a surveillance list. On October 26, the movement's webpage was hacked.

But it has not stopped her, nor is she afraid. She is currently writing an autobiography, travelling to activist conferences around the world and speaking out. Loudly. She says that like other Arab revolutions, once people realize they are being denied their freedoms, they cannot turn their backs.

It's like that first time behind the wheel of her Cadillac. "I have this feeling that you just need to jump," she says. "To trust yourself. "