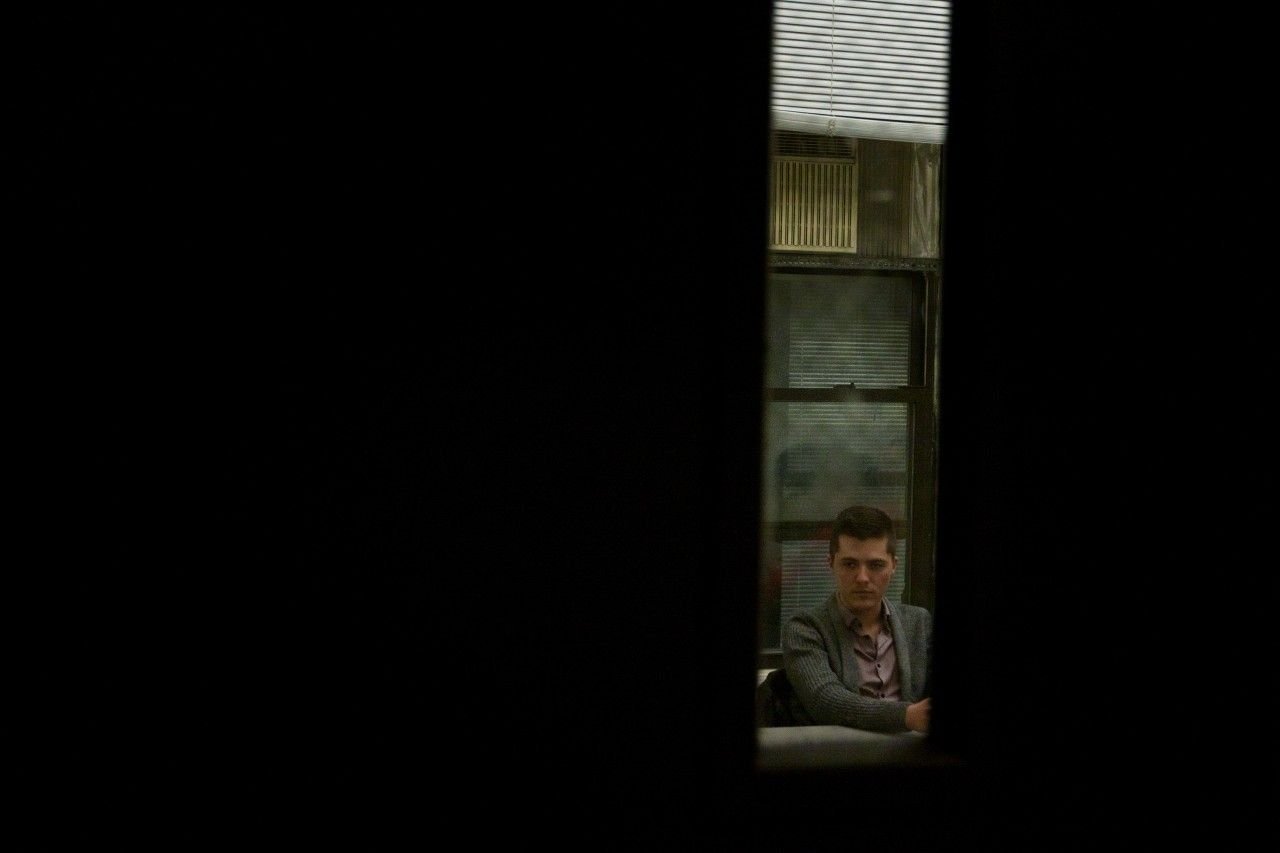

Jacob Link, 22, wryly describes growing up a megachurch poster child in Kissimmee, Fla., like he's performing a practiced stand-up routine. "People were always having prophetic dreams about me," he says. "I loved the attention."

Link regularly starred in horror-themed church pageants about immorality; in one, his character died after being kidnapped, duct-taped to a mattress and injected with drugs, which meant Link got to attend his own elaborate funeral and crawl into a coffin next to an adult dressed as Satan, who later popped up to scare the audience "out of sin." Link was nine years old. "I thought I was saving souls every night," he said.

In middle school, Link met "real gay people" for the first time through a secular theater. "I went into that audition clasping my gold cross," he recalls. "It was like meeting aliens." He quickly realized his church had misconstrued homosexuality and started asking innocent questions in Bible study. After his teacher complained, Link found himself blacklisted by the community. His parents made him shave his head and do manual labor to repent, and he eventually switched schools.

Link says he "zombied through" high school and landed a full scholarship to college, where he met his current girlfriend, whom he credits with helping him leave the church behind. But even she can't understand his past as well as the people he has met through Beyond Faith, an ex-Christian support group for New Yorkers under 30 eager to leave Christianity behind.

"The group just makes me feel less screwed up," Link says. "It seems like when you're done with religion, you should be able to move on; but, in reality, when you've built your entire life around it during your developmental years, you can't just let it go."

Beyond Faith has a serendipitous creation story. In 2012, founders Dena Roth and Geoffrey Golia separately approached Syd LeRoy, the executive director at the Center for Inquiry in New York, a secular humanist nonprofit where they both volunteer, to discuss launching a youth support group. "A lot of people in the skeptic community are older folks, so it's hard to find spaces where you feel comfortable as a young person," LeRoy told Newsweek. College students and recent graduates in particular, many of whom are transplants to the big city, need "support and community when they finally come out to their friends and family."

Golia, a social worker, says even he - a white guy who, at 30, has nearly aged out of his own group - often felt alienated by the old white men in skeptic community debate-based groups that "put so much emphasis on proving why atheism is better than theism.

"We're more concerned with taking care of believers than converting them into nonbelievers," he says. "You can be an atheist and still feel pain and shame."

Roth, a 24-year-old queer artist and activist who was raised in a Maryland megachurch and once proudly wore a purity ring to symbolize sexual abstinence, says it's difficult to relate to New Yorkers who see evangelicals as nothing more than a punchline. "Being an ex-Christian can be so isolating, even in a liberal open-minded progressive city," Roth explains. "It's true that I was raised in a bubble - my church was my entire life, and I've let it go - but it was fulfilling and meaningful, and everyone here thinks I was, like, in a cult."

Together, Roth and Golia developed a mission statement, which they posted on Meetup.com. "Beyond Faith is for the person who doesn't quite fit in with the pack, a person whose ideals and beliefs do not jibe with their peers, family members, or loved ones," the description reads in part. "This can be a tough journey, especially for those whose family and friends are unsupportive of their doubts and lack of belief.... For some, just the idea of entertaining serious doubts about faith can be dangerous and overwhelming, and Beyond Faith seeks to ease the process.... "

The founders believe young nonbelievers have different needs from their older contemporaries. Many young adults in Beyond Faith are still financially and emotionally dependent on their families, furious at their parents, and anxious about how to redefine themselves. "How do we emerge as adults when we're not feeling confident in the metaphysical realm?" Golia says.

"Growing up, community for me existed only in the church," Roth says. "I wanted to reclaim that. Unconditional support is a really valuable thing to have."

Golia and Roth estimate that only half their members identify as heterosexual and Caucasian. Attendees at November's monthly meeting included a former fundamentalist Bible thumper from rural Montana, a Korean ex-altar boy from New Jersey, and a Peruvian college dropout whose father is an evangelical minister.

But all the members have notable similarities, too. All solidified their religious skepticism in college, once they were away from their families for the first time. Many struggled academically, thanks to the trauma of leaving both home and Christianity while also trying to keep grades up. And they all have a hard time stopping themselves from instinctually lapsing into prayer, since "superstition is the default," even if the invocation is in the name of the Red Sox.

During the meeting, group members sat in a fluorescent-lit rehearsal room on Manhattan's Lower East Side and giggled over Christian buzzwords and slogans like "Unharden Your Heart" and "Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve." Moments later, they solemnly discussed how to resist acting like "superior atheists" around friends and attempted to unpack their complicated relationships with their pasts. "There was nothing that wasn't framed by my relationship with God," one young man muses, "So how can I be the same person?"

"It f**king sucks," Golia says in support. "It hurts."

Several Beyond Faith members later opened up about their painful childhoods in private interviews.

Francis can pinpoint the moment she felt most alone in the world. She was 12 and "pretty nerdy for a black kid," a loner raised by Pentecostal Church Elders in South Florida who fretted over her unkempt hair and nonconformist nature. Although her life revolved around religion, she says she has considered her faith "a hindrance" ever since she was a little girl. Still, one afternoon, Francis tried as hard as she could to harness the fervent emotion her friends radiated when they praised the Lord and spoke in tongues.

"I thought: Please feel something, anything; feel it, feel it," Francis recalls. She couldn't.

"I've never felt more lonely. I remember asking myself whether I had the emotional capacity to feel anything, if I would ever feel loved."

Now, Francis is a 26-year-old "apathetic agnostic" who has finally found a like-minded community. "In my darkest moments, my first instinct is still to pray, even though I know it's not going to help me," Francis said. Thanks to Beyond Faith, she was able to replace prayer with a secular support system. "You create your own family in that group," she says. "It vindicates you. It makes you feel like you're not alone."

Renato Rengifo, 24, has had a particularly rough time letting go - until three months ago, he was living at home with deeply religious parents who refuse to accept that he is gay. "I can't even describe how refreshing the first meeting was, how invigorating," says Rengifo, who started attending meetings earlier this year. "I needed people to say, 'I understand how pathetic you feel right now trapped in a mindset that you know you want to get away from but you can't.'"

Rengifo says Beyond Faith's support helped him work up the courage to move out, and that his relationship with his parents was slowly improving: "Now I can talk to my parents about laundry instead of faith."

Roth ends every Beyond Faith meeting by jokingly suggesting a prayer (even though a new member once took the jest seriously and briefly freaked out). There are no sermons at Beyond Faith, but there is solidarity: After the last meeting, group members hugged each other tightly outside in the cold before reluctantly heading their separate ways. "It's hard for us to let each other go," one smiles. No one laughed at that.