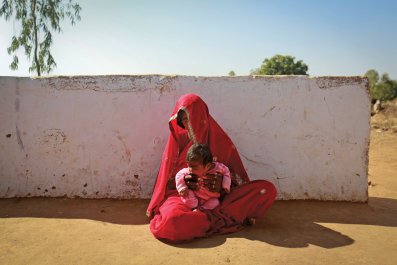

OLDER PARENTS of new babies sometimes feel that they are swimming against nature's current, spawning in their 30s or 40s and not in their friskier 20s. A woman's fertility is known to decrease after age 30—and especially after age 35—and the risk of genetic abnormalities in offspring increases. Well, there's finally some good news for the not-so-young set, a silver lining for those who may have a few silver hairs.

As reported in the journal PLOS ONE, investigators from New Zealand looked at 277 kids who were born after a normal, full-term pregnancy. When studied, the children were between 3 and 10 years old—not yet grown up but with a predictable growth trajectory. The researchers recorded their height and weight, took a few blood tests that may predict growth, and then sorted their findings according to whether the child was born when the mother was in her 20s or already had crossed the line into life as a 30-something.

By a significant margin, children born of older mothers were the clear winners: they were much taller and thinner than those whose mothers were younger. The difference wasn't because the older parents were themselves taller and thinner; in fact, the researchers weren't sure how to explain the findings, which are in line with observations made a few times in the past. Perhaps, they suggested, the hormonal mix produced during pregnancy by an older woman differs from that made by her younger counterpart.

This study comes along as more and more women have children later in life. As the report points out, in the last 30 years, "maternal age at first childbirth has increased by approximately 4 years in most developed countries," meaning that in the richer part of the world, "most children currently are born to mothers aged over 30 years." Accordingly, the age of the parent has been receiving increased scrutiny from neurodevelopment experts. Recent articles, for example, have suggested that children with older fathers have an increased risk of autism and related autism-spectrum disorders. This new study pushes back on the assumption that youth is all—and reminds us that understanding the risks and benefits of having children later in life can be a tall order.

KENT SEPKOWITZ is an infectious-disease expert in New York City.