War is not child's play—except when it is. In a new exhibition called War Games, which opened May 25 at the V&A Museum of Childhood in London, curators Ieuan Hopkins and Sarah Wood bring together more than 100 objects in an effort to explore how the worlds of warfare and childhood have intersected and influenced each other since 1800.

Today, many of these objects—Get Rid of the Huns, a British puzzle from 1914; a deck of cards hand-drawn by Buchenwald prisoners; a doll's house designed to teach soldiers about house-to-house combat—can seem "quite horrific," admits Hopkins. "But once children get a hold of them, the imagination takes hold, and you have Boer War soldiers fighting space aliens with World War II bombers flying overhead. War surrounds us. It surrounds children. Toys—and play in general—are just ways for them to make sense of the world."

Below, Hopkins and Wood give Newsweek a tour of a dozen key objects from the exhibition.

Toy Soldiers, El Teb, 1885

Ieuan Hopkins: They're little tin soldiers. They were very cheap to make. They were very quick to make. Manufacturers wanted historical accuracy, so they would base the figures on the press and images contemporary with the event. The Battle of El Teb would be reported in the Illustrated London News, and then those images would be used to form the basis of the soldiers. So the soldiers are in the same poses; their uniforms are the same. Each time a new battle occurred, or a new action, then it would be represented in these soldiers. You're telling a story when you're playing with these things.

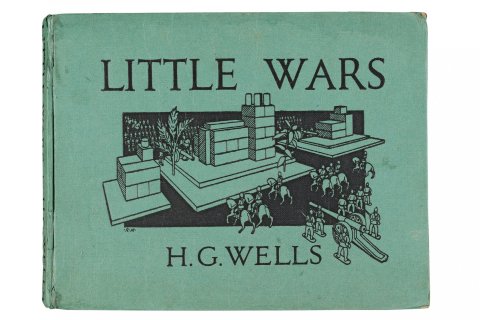

H.G. Wells's 'Little Wars'

Hopkins: Little Wars is a book that Wells wrote in 1913, on the eve of World War I, that basically stemmed from him playing with toy soldiers in the nursery and the dining room of his house. He would play it with his adult friends. It's not something he did for children. It's amazing how many cabinet ministers and well-known politicians and writers used to pop around to H.G. Wells's house to get on their hands and knees to play Little Wars with him. He was a pacifist, so his idea was that all of the people talking about war should be made to go to some sort of war-game temple and play Little Wars, and in that way get out their aggression and desire for war so the rest of us can carry on normally instead of going off to fight.

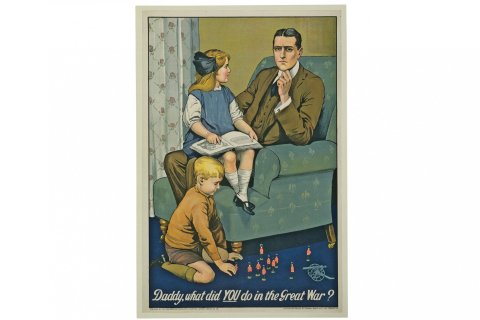

World War I Poster

Sarah Wood: This is a poster that was made before conscription happened. It introduces the idea that war pervades society. It's basically a guilt trip. You've got a father sitting there, two children around him, playing with a set of toy soldiers on the floor, and it was actively done with the idea of that male in mind—as propaganda to encourage him to sign up.

Hopkins: It shows that war gets right into the heart of the home and it affects children in that way. It's not something that happens only in a distant country. Parents fight in wars. Friends, brothers. The war is very often brought back to the kitchen table or discussed around the fire in the evening.

Louis Marx Tank

Wood: This is a First World War tank. It's an example from the 1920s. Photographs of the first tank came out in 1916, and the first toy tanks were made only three months later. It represents the changing technologies of the time: from cavalry and infantry into the mechanization of war.

Hopkins: Children were fascinated by these technologies: aircraft, zeppelins, and balloons; submarines, tanks, trenchers. And not just kids: when these toy tanks came out, people gathered around toy shops to look at them, and the toys became a way for civilians to get information about the world and the war.

The Führer's Limousine

Hopkins: This is a tin-plate car. It's got the führer seated in the back and three bodyguards around him. It was made in Germany during the Second World War by a company called Tipp and Co. It was originally a Jewish firm. They were based in Nuremberg, where a lot of the anti-Jewish attacks kicked off, and so they fled Germany in the 1930s. But the company kept manufacturing toys under the ownership of the Third Reich, and this was one of the toys that was produced at the time. With this, we wanted to show that the toy industry operates within the context of global history and global events. War impinges and affects children's lives in many ways, and this car—a model of Hitler's limousine made by a Jewish firm—seemed to be quite a poignant way of pointing this out. It's a good window into society at the time, really, and the way the political intersected with the world of children.

Brownshirts

Hopkins: Toys mirror warfare: the technology, the uniforms, the new organizations being produced, the new nations being produced. These figures were made at the same time as the führer's limousine—the late 1930s, the early 1940s. Toy soldiers had sort of dropped off in popularity by the 1930s, but when the Third Reich came to power and began to form all of these political organizations, toy companies could suddenly produce these sorts of figures. There was never any sort of official dictate saying toy companies should produce these toys. But the companies sensed there was a public feeling at the time, a public demand for toys representing not just Brownshirts but every political figure at the time. So you could buy Hitler in many different uniforms. Göring and Goebbels, too. All the leaders of the Third Reich were depicted in this way, as toys for children. They were designed for children to buy and play with.

Johnny Seven Gun

Wood: The Johnny Seven was introduced in 1964, and it was one of the most popular toys of the 1960s. It's about 60 or 70 centimeters long; it's got various grenades and handguns and all sorts of bits that can be attached and detached. So it's got a broad play purpose. But it's also an incredibly violent concept.

Hopkins: The Johnny Seven was quite short lived, actually. It was popular for a couple of years, just before the anti-war movement kicked in and toy manufacturers started shying away from it. So I suppose in some respects it was kind of the last hurrah for toy guns.

Wood: Realistic ones, at least. During Vietnam, there was a general move away from representing the realism of war. And so, with the space race and atomic weapons, war very much went into space. Sci-fi and superheroes. That's where the demand for war toys went after the 1950s and 1960s.

G.I. Joe

Wood: G.I. Joe was the first action figure for boys. He replaced the mass of toy soldiers, and the model became a singular figure instead: the all-American fighting hero who encapsulates the values of the Army.

Hopkins: In the past, wars were fought on the battlefield. You would have regiments moving forward at the same time. When you get into the 1960s and 1970s, war itself becomes more fragmented, and moving into the Cold War, the actual battles become invisible. They're fought by individuals dropped behind enemy lines. They're fought by snipers stuck up in a tree somewhere. This idea of mass movement and commanding groups of people almost like a chess game doesn't really resonate as much.

Wood: Enter G.I. Joe. He was a marketer's dream, really: you buy the action figure, and then you can buy endless, endless amounts of kits for him, including different weaponry, different vehicles. That's one of the reasons war toys have been so appealing and enduring. There are endless possibilities, with different battles and different uniforms and different sides and how you choose to use them.

Hopkins: People had seen how successful Barbie had been, and they thought, how can we do this for boys?

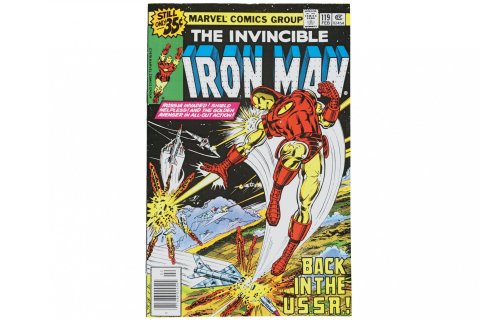

Iron Man

Wood: This is that reality-to-fantasy thing I was just talking about. Iron Man really encapsulated the Cold War. He starts off in Vietnam, and then by the 1970s, which is the comic that we have here, he's fighting in outer space—going into Russian airspace and causing problems. And remember: Iron Man's alter ego develops weapons. He's very much in parallel with the people in those Cold War governments. It's a pretty thinly veiled bit of fantasy.

He-Man

Wood: He-Man came out of the relaxation of the advertising laws on television. So instead of having short commercials, you were allowed to have up to 30 minutes of airtime to promote your products. And that became the Masters of the Universe cartoon. This was one of the major turning points in the reality-to-fantasy transition: once those floodgates were open, there was a much clearer line to children, and products could be directly sold to them.

Hopkins: After children's advertising was deregulated, within two or three years something like 90 percent of toys were based on or had their own television shows. It was amazingly quick and all-pervasive.

Wood: We tried in this exhibition to get away from the idea of the toymaker as an old man with the beard and the lathe handcrafting some little toy soldiers. The toy industry is a huge, huge industry, and it reacts and adapts to make money just as any other industry does. It's capable of huge feats of engineering and very canny marketing.

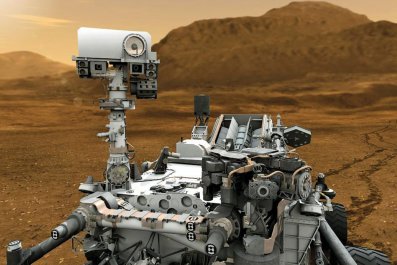

HM Royal Air Force

Hopkins: This is a forward air controller [not pictured] for the HM Royal Air Force: the guy who's on the ground in Afghanistan, who points a laser at a target, and then a missile is shot out of an aircraft 20 miles away. And the interesting thing is that this toy is licensed by the British government. They do a whole range of these. Each type of toy is checked by the government to make sure it's accurate, and they're very open to the fact that they're doing this to interest younger children in a possible military career. In a subtle way, it can be viewed as a tool of recruitment. Going back to the Victorian era and the First World War, much has been written about toy soldiers and other aspects of children's material culture being used to further children's militarism and nationalism. And you think, that's fine, it probably did happen back then. But then when you bring a contemporary object in and compare it, then you see that maybe things haven't changed as much as we think.

Stick Guns

Hopkins: My son picked these sticks up in a wood and started shooting with them. That's all. While the War Games exhibition concentrates on mass-produced toys, we also want to get across this idea that children don't need toys to play at war. Everyone has picked up a stick at some point and used it as a sword, used it as a gun. It's a war game but without rules—without anything being imposed from the outside. Maybe there's an innate attraction. Running and hiding and shooting? You don't need anything but a stick to do that.