It's a rainy morning in Los Angeles, and Elisabeth Moss, who plays Peggy in the television series Mad Men, is standing outside the stage door smoking. On the set the actors are restricted to herbal cigarettes, which is why she has ducked out for what she calls "the real thing." I explain who I am (a reporter from Newsweek) and why I'm there (I started as a secretary), and she exclaims, "I am you!" Moss's character, Peggy Olson, is a striving Norwegian-American Catholic girl from Bay Ridge, Brooklyn (coincidentally my birthplace, too), who starts her career in 1960 as a secretary "straight out of Miss Something secretarial school," she says. That was the path then for women, and as Mad Men enters its fifth season on AMC March 25, Peggy has gained recognition for her skills as a writer, rising from Don Draper's secretary to his trusted No. 2 in the creative department at the fictional ad agency Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce. Her success is not without cost, as she puts her personal life on hold. Moss says a woman like Peggy "didn't want to take men down and cause a ruckus; she loves writing, that's all, and wanted a chance to do it."

Women weren't supposed to be openly ambitious in the '60s. When I started at Newsweek As a secretary, I was thrilled to be where what I typed was interesting. I was the daughter of immigrants, my father had a deli, and my mother made the potato salad and rice pudding. It didn't occur to me that I could be a reporter or a writer, but the frustrations that within the decade would produce a women's movement were taking root at Newsweek.

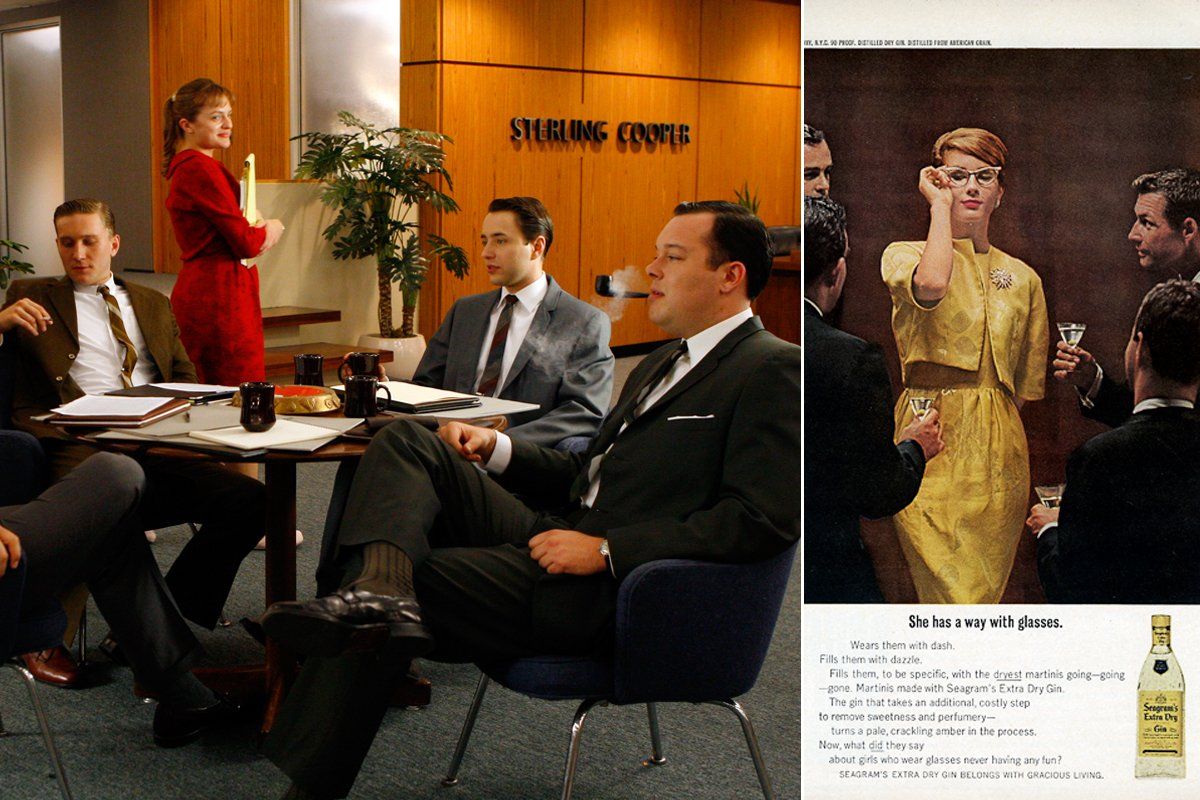

The two days I spent hanging around the set of Mad Men were like entering a time capsule that took me back to that period in the '60s, everything from the pencil skirts and stockings with garters to the electric typewriter that was the latest technology. Critics have assailed the way everybody on the show smokes, glorifying a nasty habit that carries significant health risks. But that's the way it was then. The public high school I attended in Queens even let us out for a smoking break.

Luck Be a Lady: Mad Men accurately reflects the Madison Avenue advertising culture that created the Marlboro Man and had doctors offering testimonials about their favorite brand of cigarette. When Draper, the agency's creative director and Mad Men's protagonist, comes up with the tagline "It's toasted" for Lucky Strike, he's told that all brands are toasted. Without missing a beat he says, "Everybody else's tobacco is poisonous. Lucky Strike's is toasted." The remark illustrates the central theme of Mad Men, the making and selling of the American Dream by Madison Avenue in the early '60s—before civil rights, feminism, and antiwar protests forced a great awakening on the ruling class. The actors who play these retro characters are all too young to have experienced the '60s and think of the era as "the good old days," but that's true only if you happen to have been born white and male and heterosexual.

Much of Mad Men revolves around Draper's extramarital exploits, and the callous way he treats the women he beds, including his wife. But he isn't exactly what he seems, and in some ways he is more respectful of women than any other character on the show because he is able to recognize and reward merit without having his manhood threatened. Peggy benefits the most, achieving professional status at a time when that was not commonplace for women, and yet she struggles with what she's missing. "Should I have married? Should I be having babies? For a 26-year-old, the pressure of having children is very present," Moss says of her character, who secretly gives up a baby after not even knowing she was pregnant. The biological clock had yet to be named, but it ticked loudly for 20-somethings then, and the more Peggy succeeds at work, the fewer options she believes she has in her personal life.

It's hard for Joan, the siren queen of the secretarial pool, played by Christina Hendricks, to watch Peggy get ahead. Joan is the embodiment of what society has told her: a job is a step on the way to creating a family, a dating game until she meets the right person. Joan has a torrid office affair with a senior partner and doesn't feel shame or guilt. She knows she's a prize, and if she plays her cards right, who knows? She marries a doctor, but he's not what he seems, and there is a scene where he rapes her. Date rape and marital rape were unheard of then, and Hendricks turned it into a teachable moment off the set when people would say, "When you sort of got raped?..." "What does that mean, 'sort of?'?" she would reply. "Just because there wasn't a knife to your throat?"

The Tender Trap: Madison Avenue did a lot to create the show's other main female character, housewife Betty Draper, with her handsome husband, adorable children, home in the suburbs, and all the appliances required for a happy existence. The fact that she isn't happy is Betty's story, and the story of millions of college-educated women who were sold what turned out for many to be a bill of goods. Betty epitomizes "the problem that has no name" that Betty Friedan wrote about in her 1963 book, "The Feminine Mystique." Played by January Jones, a frustrated Betty tries a brief return to her modeling career (which Don squelches), horseback riding, another baby, then divorce and remarriage. Betrayed by her husband and cold to her children, Betty is defined by her dissatisfaction. "I understand her psyche, I know where she's coming from," says Jones, "but there are times when I dislike her." Betty's relationship with daughter Sally, played by 12-year-old Kiernan Shipka, is especially combustible and promises rich storylines as the adolescent Sally begins to understand how powerful she is, playing her divorced parents against each other and mirroring the growing turbulence that we think of as the '60s.

Mad Men gets the gender stratification of the time right, along with the prevalence of smoking, the heavy drinking culture, and a fair amount of sleeping around. That was certainly the case at Newsweek In the '60s among the married writers and editors and the young single women hired to become researchers, then considered "a really good job for a woman." Newsweek's training program recruited women from the finest colleges for a stint first on the mail desk, then the clip desk (cutting articles from newspapers), and finally a coveted spot as a researcher. I soon became aware that aside from me, the women working at the magazine were all graduates of the Seven Sisters colleges or other elite universities, had all been to Europe, and on their lunch hour either went shopping at Saks Fifth Avenue (then right around the corner from Newsweek) or visited their therapist. These smart, talented, and ambitious women were primarily fact checkers, but they also did reporting and were expected to provide emotional support when the men were doing their writing, everything from sharpening their pencils to picking up their dry cleaning.

Diehard Mad Men fans may recall that the tale of one Newsweek Researcher made its way briefly into a Season 3 episode, when a radio broadcast tells of the murder of two young women, Janice Wylie and Emily Hoffert. Wylie, the researcher, didn't show up for work on Aug. 28, 1963, and it was assumed she had taken the day off to join the March on Washington where Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech. When she and her roommate were found, the headline was "Career Girls Murders." The message drummed home by the media was that this is what happens when girls leave the fold and live as single women in Manhattan.

The reality for most single working women was, of course, much more prosaic. A former Newsweek Researcher recalls two of her colleagues being dispatched to a nearby bar to order martinis for the male writers and bring them back in paper cups stashed in their purses. The drink of choice was the martini, which former Newsweek Writer Peter Goldman recalls being served in "glasses the size of birdbaths." The three-martini lunch was real, not just an expression. How could anyone write after consuming so much alcohol? Another former Newsweek Writer would say, "The great thing about this job is you can do it drunk." Goldman recalls returning from the magazine's traditional Friday-night dinners "lightly buzzed—it was relaxing, like a Valium."

Don Draper would have felt right at home at Newsweek. While I don't recall any of the top editors having a bar in his office, a couple of the writers had bottles secreted in their bottom desk drawer. The abundance of young single women would also have been easy prey for Draper, whose prowess with women provides endless plot twists to examine how people lie to each other and themselves. For the record, actor Jon Hamm is in a committed relationship and nothing like the character he plays. The son of a '60s-style executive who had a closet filled with expensive suits before the bottom fell out of his family-owned business, Hamm inhabits Draper's complexities. In last season's final episode, Draper surprises everyone by getting engaged to his new secretary, conveying the news over the phone to the woman he'd been seeing, a consumer psychologist who is his professional equal. She is devastated. If there are two paths, says Hamm, Don always takes the easier one, which in this case is a much younger, unformed, hero-worshiping secretary.

Wives and Lovers: Like Draper, many editors and executives maintained families in the outlying suburbs while behaving as though it was their God-given right to enjoy playtime in the city. Goldman, hired as a writer in the National Affairs section in 1962, recalls a fellow writer telling him he was the most married man at Newsweek, "and he didn't mean it as a compliment." Everything flourished at Newsweek, from brief affairs to deeper bonds that functioned like office marriages, with some enduring beyond the office. In a scene that would fit right into Mad Men, a former researcher recalls receiving a negligee with matching mules and boa feathers for Christmas from a married editor. Horrified at where their friendly lunches might be headed, she packaged it back up and brought the unwanted gift to him at the office. "It was a joke," he said lamely.

An infirmary on the 13th floor with two rooms that could be locked was a favorite place for trysting. I didn't participate in these extracurricular activities. Not that I was superprincipled, but I was living with a television director I had met at a previous job working as a secretary at ad agency Albert Frank-Guenther Law. Brooks Clift was charming and worldly; he gave me books to read and talked to me as if my opinion mattered. Thrice married and 21 years older, he could have stepped off the set of Mad Men. He would become my husband and the father of my three sons. We were married at the home of his brother, actor Montgomery Clift, with my future mother-in-law gesturing to the heavens to reassure my mother that only God knew whether this union would succeed. The Clifts won her over—and my mother, who never drank, got tipsy on a few sips of liqueur and was soon giggling on the sofa with Monty.

It Was a Very Good Year: When I meet with Matthew Weiner, creator of Mad Men, he proudly shows me the "chip and dip" platter that was a wedding gift to his parents. It's a garish green with a red tomato shape in the middle to hold the dip. "This is my age," he exclaims. "I was raised by people who married in 1959, and you get your parents' values if you're lucky enough to meet them." Growing up in the '80s, Weiner's generation was obsessed with "M*A*S*H" and "Happy Days" and 1950s diners. It was a conservative time, he says, and when he got to college there wasn't a lot of sleeping around because of AIDS. The '60s were remembered as this glorious period when there was free love and society threw off its shackles, and Weiner wanted to know more.

He describes his father, a neurologist, as "very virtuous." He first learned his father was Ronald Reagan's doctor when Nancy Reagan revealed the former president had Alzheimer's. His mother, a lawyer and then a stay-at-home mother, is like Betty Draper, "given lots of power and education and expected to ruminate the rest of her life," he says. A rare hint that Weiner offers about the upcoming season has to do with the perennially unhappy Betty, who is remarried to political operative Henry Francis, director of public relations and research for New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller. "The idea that Betty Draper is going to read a book and become a feminist ain't happening," he declares, adding, "She may find enlightenment some other way."

The show, produced by Lionsgate, has won praise for its historical accuracy, and when I was visiting the set, costume designer Janie Bryant brought Weiner a sketch of vintage rubber pants that had been designed for toddler Eugene, Betty and Don's third child. They don't make them anymore for babies, she explained, because they're toxic—another reminder of how much we've learned about health and safety in the intervening years. One scene from the first season had young Sally Draper running around with a potentially lethal plastic bag over her head, playing spaceman with her friends, while all Betty worries about is that her clothes had better not be wrinkled.

Weiner can handle seven or eight characters in his head, and he dictates the storylines to a writer's assistant, pacing while he talks. "It would appear psychotic to a stranger," he says, even as he emphasizes, "It is not stream of consciousness, it's very organized." The dictation is given to the writers' room, where a dozen or more writers turn it into a first draft that Weiner then rewrites. "It's way easier for me to rewrite than starting at zero," he says.

The Best Is Yet to Come: Assured of three more seasons after contentious negotiations, Weiner is already getting questions about how he will end Mad Men. Imagining Don and the others today is unlikely: "unless they're freaks of nature, the way they drink and smoke" they probably wouldn't make it into their Medicare years, he says.

"I don't want Betty to be in her 80s and in spandex," says January Jones. "Kill me off before then, please." Jones quickly rethinks what she has said, reminding herself that she has two grandmothers "and they are in spandex. You should rock it if you can." Weiner thinks that what the show's fans are looking for is assurance that he can bring the series to a satisfying conclusion. "Don't just use a scissor to cut the ribbon," he says. "They just want to know that I know, and I think I do."

As the world of Mad Men enters the mid-'60s in Season 5, the times they are a-changin', and Don Draper and his buddies are on the wrong side of the gender and generation gap that will leave America a radically different nation by the end of the decade. At Newsweek, A cover story on "Women in Revolt" appeared on newsstands in 1970 the same day women at the magazine held a news conference announcing they were suing for gender discrimination. The class action, launched by a half-dozen researchers in New York, was ultimately joined by 46 women. The editor, Osborn Elliott, a fine journalist who thought of himself as a progressive, was both surprised and truly hurt by the women's action. During a meeting with the women and their ACLU lawyer, Eleanor Holmes Norton (who now represents Washington, D.C., in Congress), Elliott sought to defend his record by highlighting the magazine's commitment to finding black writers, correspondents, and editors. To which Norton replied sharply: "Mr. Elliott, all you're telling me is you've got two problems."

Newsweek had been focused on civil rights and the growing antiwar movement, and by the time the male editors got around to the women's movement, discontent within the magazine had taken hold and legal redress was essential. An affirmative-action plan opened up opportunities that I could never have imagined, and after an internship I was assigned to cover Jimmy Carter's bid for the White House, which brought me to Washington, where I have been ever since. It's my Cinderella story, and it's an era that Mad Men captures in all its dimensions. A lot of positive social change took place, the result of struggles waged by many people whose names don't make it into the history books. To be part of it in even a small way sure was fun.

Correction: A previous version of this article erroneously reported Weiner's parents divorced when he was 10. They have been married for over 50 years.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.