Ever since the Ebola outbreak began earlier this year, scientists have been scrambling to test therapies and fast-track the most promising options to treat the disease.

Patients brought back to the U.S.—including Kent Brantly, Nancy Writebol and Rick Sacra—have been treated with a combination of ZMapp, an experimental drug and blood transfusions of Ebola survivors. But now that the first Ebola case has reached U.S. soil—and the epidemic in West Africa continues to balloon, with some experts expecting the number of infections to rise into the millions by 2015—the demand for an effective treatment that can be distributed to thousands of people is growing exponentially.

A few experimental therapies have been in development, but so far the most promising is ZMapp, which was created by Mapp Biopharmaceutical, Inc., in collaboration with LeafBio in San Diego and Defyrus Inc. of Toronto. After ZMapp was successful in monkey trials and possibly helped save the lives of Brantly and Writebol, Mapp increased its production and sent a limited supply to West Africa. But that supply was completely exhausted by mid-August.

The fact is, an Ebola vaccine or cure hasn't yet been developed because it simply was not a priority for years. "Ebola is a relatively recently discovered disease with sporadic outbreaks, and like some other emerging pathogens affects a relatively small population compared to malaria, AIDS, and other diseases which have tremendous public health impact and which are still very poorly controlled despite enormous effort worldwide," Mapp Biopharmaceutical stated. In other words, researchers and drug companies have had bigger fish to fry in battling more widespread and impactful infectious diseases.

This is why it new treatments appear to be lagging behind, even when fast-tracked with aid from the government, international organizations, and charities. The WHO released a statement noting that "existing supplies of all experimental medicines are either extremely limited or exhausted. While many efforts are under way to accelerate production, supplies will not be augmented for several months to come. Even then, supplies will be too small to have a significant impact on the outbreak."

But a new $5 million initiative spearheaded by the Wellcome Trust to fast-track clinical trials in West Africa for a number of experimental drugs might soon get the wheels turning a little quicker. These trials will involve the use of drugs from companies including Mapp, Sarepta Therapeutics, and Tekmira Pharmaceuticals. Tekmira just gained FDA approval to use its TKM-Ebola drug on "confirmed or suspected cases" of the disease. CEO Chris Garabedian of Sarepta announced last week that the company had about 100 doses of its Ebola drug but that it would require more money and more time to increase production to the thousands.

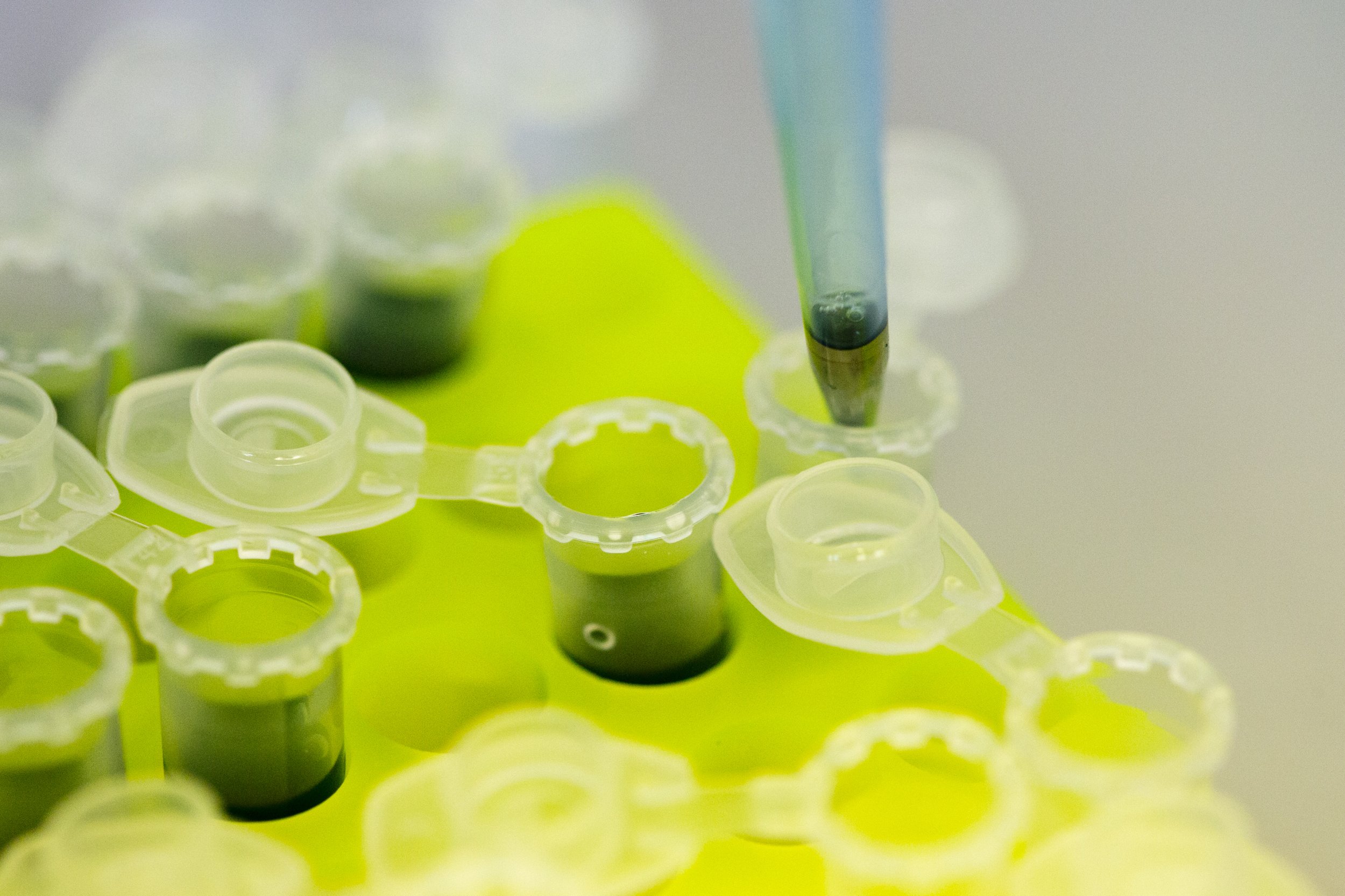

ZMapp, the drug holding the most promise, will experience boosts in production through a number of avenues. The production of ZMapp through tobacco leaves essentially involves infecting tobacco plants with a genetically engineered virus that produces antibodies, which can then be used in the drug. The original doses of ZMapp that were used to treat Brantly and Writebol were produced in tobacco leaves at a Kentucky facility, but it's a slow-moving process; this is why the the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has enlisted Caliber Biotherapeutics to help produce ZMapp in millions of hydroponically grown tobacco plants in a bigger capacity. Meanwhile, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is working with a number of biotech companies to see if they can produce ZMapp in animal cells, instead.

But none of these developments will happen overnight, as HHS is still working on finalizing contracts with Caliber and other companies. In addition, these drugs are all still considered experimental, meaning no one quite knows whether they're completely effective—or even entirely safe.

"It is a huge challenge to carry out clinical trials under such difficult conditions, but ultimately this is the only way we will ever find out whether any new Ebola treatments actually work," Jeremy Farrar, Wellcome Trust's director, said in a statement. "What's more, rapid trials, followed by large-scale manufacturing and distribution of any effective treatments, might produce medicines that could be used in this epidemic."

What they need now is time—something the Ebola patients in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Nigeria and Guinea don't have.

"The Ebola situation in West Africa is an ongoing tragedy of immense proportions and we urgently need to know whether any of these investigational treatments can save lives," Dr. Peter Horby, associate professor of infectious diseases and global health at the University of Oxford, said in a statement. "In essence we need straightforward clinical trials, as for any drug for any disease, but new ways of working will be needed to provide rapid and reliable answers in perhaps the most challenging outbreak we have ever encountered."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.