The United Kingdom has been front and center in the public eye this summer thanks to the Diamond Jubilee and the Olympics, whose opening ceremonies served up a pageant of quintessential Englishness, from Victorian stagecoaches and cricket to James Bond and the queen. The timing could not be better, then, to celebrate Britain's national heritage—and the British Library is doing just that with "Writing Britain: Wastelands to Wonderlands," on display through late September.

The exhibit takes as its theme the ways in which the U.K.'s landscapes—the white cliffs of Dover, the austere Highlands, Soho's bustling streets—have inspired some of the world's greatest literary works, and how the land in turn has been transformed by stories in which Britain itself is as vivid, complex, and alive as any hero or villain. From Robin Hood's Sherwood Forest to Tess's rural Wessex and the London of Sherlock Holmes and Clarissa Dalloway, the exhibit explores the places, both fictitious and real, that are intimately bound up with the literature of the British Isles.

The works—over 150 novels, poems, and plays, many from the British Library's own archives, along with recordings, maps, and drawings—are organized into six sections, each covering a particularly fertile pocket of imagined space. First up is "Rural Dreams," which looks at the British countryside as an idyllic retreat from the world's ills. Here we find Albion, that mythic isle where Druid legends still haunt the wild green land. Here is Edward Thomas at his train stop listening to the birds of Adlestrop, and the stately manors of Darlington Hall and Brideshead. Here are Shropshire lads and happy shepherds, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and numerous variations of those ancient "green [men], legend-strong, reborn," who "moved through Britain, bright and dark, like ale in a glass," as Carol Ann Duffy writes in her lush poem "John Barleycorn." John Clare, the peasant poet, makes an appearance, as does Aemilia Lanyer, rumored to be the Dark Lady of Shakespeare's sonnets. Most enchantingly, the section features original artwork of Hobbiton-across-the-water by J.R.R. Tolkien, whose threatened Shire harks back to the preindustrial hamlets of his youth.

If "Rural Dreams" represents Britain at its most picturesque, then "Dark Satanic Mills"—a phrase from William Blake's "Jerusalem"—shows one of the ugliest periods of the nation's history. Industrialization wrought massive changes upon England, and its legacy still haunts parts of the country. Contemporary writers were shocked at the squalid conditions of factory towns, whose fiery furnaces churned out "thick sulphureous smoke, which spread like palls," in the words of one 18th-century poet. Frances Trollope penned the first industrial novel, about Lancashire cotton factories where starving children scavenged from pigs' troughs. Charlotte Brontë set her Shirley in the "soot-vomiting mills" of the Yorkshire textile industry, and Charles Dickens invented the wretched fictional mill town Coketown for Hard Times.

By the mid-20th century, industry began shutting down, leaving behind poverty and decline. Local writers documented the downward spiral of cities like Birmingham, Manchester, Nottingham, and Leeds. In "Hodbarrow Flooded," Norman Nicholson watches the sea reclaiming a once-prosperous iron-ore mine. W.H. Auden invokes lead-mining towns in "Amor Loci," where "here and there a tough chimney/still towers over/dejected masonry." And Ted Hughes explores Yorkshire in The Remains of Elmet (the Celtic name for the Calder Valley), where he finds the ruins of industrial enterprise overrun by vegetation: "Before these chimneys can flower again/they must fall into the only future, into earth."

The sense of ambivalence that the writers express about the postindustrial North—finding a poignant beauty in its decay—re-emerges in the exhibit's sections on "Wild Places" and "Waterlands." Britain's moors and bogs, mountains and lakes, rivers and seascapes are both awe-inspiring and menacing locales, where a visitor is as likely to experience a deep spiritual renewal as to go mad. Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights paints a land of raw elements, which both liberates and destroys her tumultuous lovers. Sylvia Plath echoes the unease of the place in her own "Wuthering Heights," written during a trip to visit her in-laws: "If I pay the roots of the heather/too close attention, they will invite me/to whiten my bones among them." During the same trip, Hughes penned a poem depicting his wife's elation with the forsaken landscape: "The moor/lifted and opened its dark flower/for you, too ... You breathed it all in/with jealous, emulous sniffings."

The poems were written long before Plath succumbed to her depressions, but the reputation of the moors as a catalyst for insanity haunts the exhibit. From Shakespeare's raving Lear to the demonic Hound of the Baskervilles and Daphne du Maurier's Jamaica Inn criminals, its characters percolate with dark hints of delirium and violence. Yet the line between lunacy and ecstasy is often tenuous. Samuel Taylor Coleridge's notebook tracks his solitary exploration of the Lake District, which threw him into a state of emotional turmoil but also inspired religious awe. In less dramatic manner, W.B. Yeats's "The Lake Isle of Innisfree" exudes both joy and immense loneliness as he longs for his native Ireland.

Many of the writers who pined for Britain's rugged places lived far away in London, the churning metropolis whose boroughs and suburbs take up two sections of the exhibit. The "unreal city" is shown here from its earliest founding myths—as a new Troy in Historia Regum Britanniae—through its Imperial heyday to the postwar years when the polis swelled with new immigrants from the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia. It is the London of gaslights and river fog, of cheery Eliza Doolittle Cockneys and lurid Sweeney Todd criminals. The city calls to its literary inhabitants, prompting them to roam its streets for inspiration, as Virginia Woolf does in her essay "Street Haunting," and to transform it into the fantastical London Below of Neil Gaiman's Neverwhere, full of Black Friars and Islington Angels and curious Floating Markets.

On the contrary, the suburbs don't seem to inspire anything but antipathy. (A notable exception: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who revered them as a refuge from the "sordid aims ... of the vast Babylon.") London's hinterlands are a "leaving place" of restlessness and boredom, as Hanif Kureishi's narrator says in The Buddha of Suburbia, and they are mocked, bemoaned, and skewered as sterile nonspaces, engendering bizarre behavior and, in the words of J.G. Ballard, "dream[s] of violence."

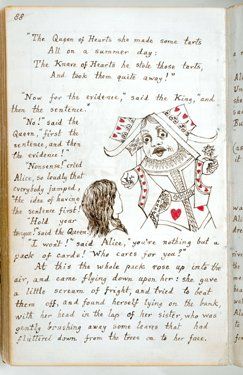

A bibliophile could easily spend hours lingering in the exhibit and discovering its hidden gems. Over here is Lewis Carroll's diary, recording the day he first spun an Alice adventure on the banks of the Thames. Over there, a lavishly illustrated Canterbury Tales; the 1,000-year-old Exeter Book; and a handwritten copy of Katherine Philips's "A Country Life," found in the pocket of Charles I's illegitimate son when he was captured in battle. There are John Lennon's revisions to "In My Life," about his boyhood in industrial Liverpool, and James Joyce's notes, in chaotic red and blue ink, on the notorious Sandymount Strand episode of Ulysses, where Leopold Bloom plays the erotic voyeur. (The scene got Joyce slapped with an obscenity lawsuit.)

Above all, "Writing Britain" shows how deeply the country has impressed itself upon its authors. Even if they move far away, Britain still calls to them: when Auden relocated to America, he kept a map of "the lead-mining world of my childhood ... my sacred landscape" pinned to the wall of his writing room. Of course, just as the U.K.'s places have affected its writers, they too have changed Britain, becoming part of the national landscape and inspiring countless pilgrimages. For proof, look no further than King's Cross station, which has now installed a Platform 9 and ¾, where Harry Potter enthusiasts line up each day hoping to make it to Hogwarts.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.