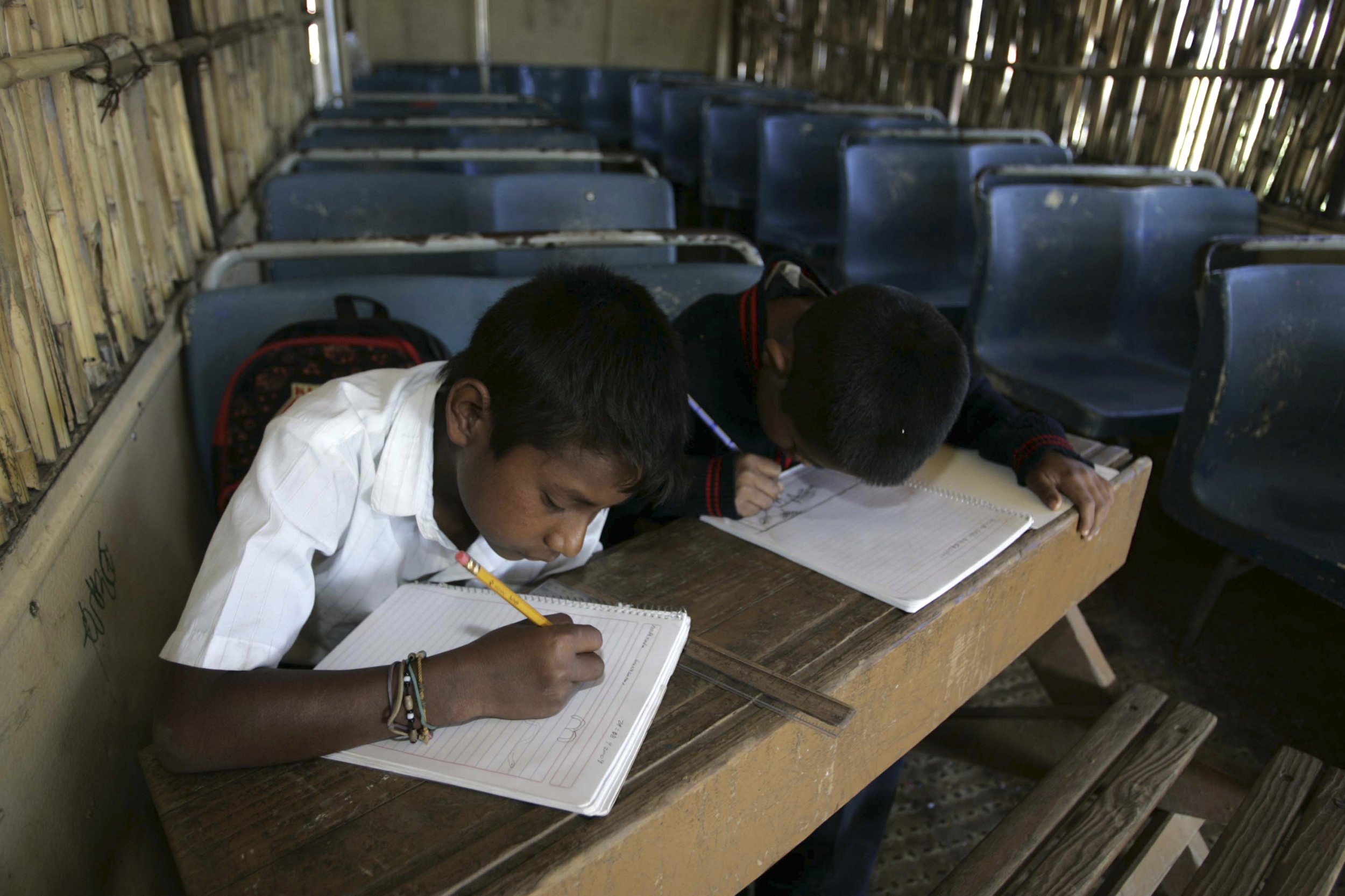

PUEBLA, Mexico—Elsewhere, it would be an unremarkable sight.

Top 10 High Schools | America's Top High Schools | Beating the Odds - Top Schools for Low Income Students

After an interactive, hour-long class, Gustavo Rojas assigns his students homework to be completed over the weekend. "Don't let me down, but, more importantly, don't let yourselves down," he tells the seventh-graders, looking around with a smile.

In Mexico, where teachers have long been known for their absenteeism and lack of preparation and students rank among the lowest performers among a group of 34 advanced and emerging countries, it is unusual to see a teacher at a public school holding his students accountable—and vice versa.

One of the pillars of President Enrique Peña Nieto's signature package of overhauls, education will have an oversized impact on his legacy. The president assumed office in 2012 amid concern that the Institutional Revolutionary Party, back in power after a 12-year hiatus, would bring back the particular brand of nepotism and corruption it perfected during its 71 years operating as a virtual dictatorship.

Its success might depend, in part, on several new programs inspired by U.S.-based models that are trying to reshape Mexico's archaic and opaque education system, which underwent a major overhaul last year. The overhaul introduced open competitions for teaching positions and set up mandatory periodic evaluations, among other things. Until recently, under a system dominated by Elba Esther Gordillo, a powerful union leader known as a socialite with a love of brand-name clothing, teachers inherited or bought their positions.

For months, radical members of the teachers' union tried to stave off the overhaul by marching down and occupying main thoroughfares throughout the country, burning government buildings, chasing legislators out of their chambers and even blocking access to Mexico City's international airport for several hours.

Though weakened, the education program was approved. The guarded but growing hope that the education system might finally start to serve the people instead of the interests of a few was bolstered by the arrest, seven months earlier, of Gordillo, the omnipotent leader of the teachers' union, on suspicion of embezzlement.

But despite recent efforts to address inefficiencies in the education system, Mexico's students continue to struggle. National standardized test results released in August show a sharp decline in reading comprehension levels since 2008.

"Mexico has to be daring and look for new formulas," says Claudio X. González, president of Mexicanos Primero, a nongovernmental organization that works for changes in the country's education sector.

TAILOR-MADE

Rojas, the teacher in Puebla, is part of Enseña por México, one of the programs that have been trying to capitalize on, and improve, the new educational climate. Part of the Teach for America corps, it had its first class of 100 recent graduates attend a five-week training boot camp last year, and, shortly after, they were deployed to several schools around Puebla state, which borders the capital, Mexico City, on the south. They are now in three additional states—Nuevo León, Mexico state and Chihuahua—and plan on expanding to Guanajuato state, in central Mexico.

Enseña por México's approach here is different than in the United States because Mexico presents several unique challenges. Only 36 percent of children who enter elementary school finish high school, only 2.6 percent of the population speaks English, and only 4.6 percent of the country's gross domestic product goes toward education, according to the Enseña por Mexico website. But most challenging of all is the culture of "it can't be done," says Erik Ramirez-Ruiz, president and co-founder of Enseña por Mexico.

"It is not a teacher's program, it is a social leadership program," says Ramirez-Ruiz. At its core, he adds, the program is trying to infuse participants with a new sense of possibility, break down social barriers—many of the participants are private school graduates who would have never considered teaching at public schools—and create a trickle-down system of ever-multiplying trained mentors.

In a sign of collaboration between new teaching initiatives in the country, two Enseña por Mexico participants traveled in July to Mexico City to attend a workshop by One World Network of Schools, an American nonprofit that trains educators to improve schools abroad.

Sitting around a small table, Aaron Brenner, co-founder of One World, asked participants to think about what makes them a leader. "I like to take charge of situations and…lean on others and delegate," says Eduardo Olvera. "I like to give my heart over.… It's not hard for me to give of myself," says Mariana Gonzalez, paraphrasing Brazilian novelist Paulo Coelho.

In August 2011, One World opened a pilot, charter-like school, one of the first of its kind in the country, in northern Mexico. Led by Brenner and Mike Feinberg, co-founder of the Knowledge Is Power Program, which now has 162 public charter schools in the U.S., it started off with 30 first-graders.

"It's not a charter school in that there is no charter law in Mexico yet," says Brenner, adding that the school, called EDUSER, works within Mexico's public school system and its students take the national standardized exam.

Rafael Pacheco, EDUSER's school leader, declined an interview, saying that the school is still too young for results to be quantifiable and that the issue of education is too politicized at the moment. Gonzalez agrees—"It is politically complicated, in the short term"—and adds that unions, which remain overwhelmingly powerful in Mexico, are the ones that stand to lose the most.

The school, which is in a rundown part of Torreón, Coahuila state, and whose students are considered underprivileged, is now in its fourth year and has 183 students on its roster. EDUSER is sponsored by Grupo Lala, Mexico's biggest dairy producer.

A second One World Network school opened last year, in Chihuahua, a state bordering the U.S. Two schools opened in Guadalajara and Monterrey in August. Like EDUSER, the other One World schools, all of which offer students free lunch, are sponsored by private donors or corporations.

But there have been challenges as well. According to a case study provided by One World Network, the leader of a school opened in Nayarit state has "not been responsive to communication." In Monterrey, Nuevo León state, two school leaders have resigned.

A COMPLEMENT, NOT A SUBSTITUTE

While education experts view these efforts as promising, they warn against calling them a solution.

Despite a recent push for transparency and growing pressure for accountability from research groups, the Mexican education system continues to rank as one of the most problematic among the 34 nations in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

Indigenous populations and students with low socioeconomic status lag far behind other students. As of 2010, public expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP remained slightly lower than the OECD average. And while mathematics performance for 15-year-olds improved between 2003 and 2009, "performance in reading, mathematics and science remains among the lowest across OECD countries," says a 2013 Mexico Education Policy Outlook report by the OECD.

Data manipulation by state education authorities also remains a problem. In May, the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness released a report revealing a number of implausibilities, such as a group of 1,440 teachers in Hidalgo state all reportedly born on December 12, 1912. The Hidalgo governor later explained that an engineer likely input the data incorrectly.

Still, projects like Enseña por Mexico and One World might sow the seeds for an eventual shift toward different and effective models.

"Both projects are positive because they bring better human capital to the country," says Claudio X. González. But, he adds, "these type of initiatives are complementary, not a substitute."

Frequently Asked Questions | Understanding the Rankings | Mapping America's Top High Schools | Newsweek's Top High Schools Special Section

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Karla Zabludovsky covers Latin America for Newsweek. Previously, she reported for the New York Times from Mexico, covering regional politics, ... Read more