For some time now, it has been a foregone conclusion among most observers that the U.S. Supreme Court is poised by next summer to end the practice by colleges and universities of using race as a factor in admissions. Still, the intensity and occasional hostility with which the court's conservative majority grilled proponents of affirmative action at oral arguments on October 31 in two soon-to-be-landmark cases left its supporters pondering a previously unthinkable question: Will any approach to leveling the field for disadvantaged minorities be left come June, when the justices are expected to render their decision?

If the court determines that any benefit or preference based on race is unconstitutional, the impact would radiate far beyond elite colleges. Supporters fear and opponents hope that the court could gut a half century of programs and laws designed to help groups that have historically faced racial discrimination in the U.S. level the playing field, giving them greater access to education that might improve job opportunities and economic equality. At risk beyond preferences in college admissions: Government programs that require a certain percentage of contracts go to minority-owned companies. Scholarships and financial aid based on race or ethnicity. Hiring practices at private companies aimed at recruiting underrepresented groups. Race-specific outreach by social services agencies. Even hate crime laws could be in peril.

"There'll be implications in employment law. There'll be implications in other areas of education. There'll just be widespread implications," says Cedric Powell, a law professor at Howard University and author of Post-Racial Constitutionalism and the Roberts Court. "People have structured their lives in a certain way around this precedent. To say it no longer exists, that's going to change things across the board."

For the court to make such a ruling would undo a precedent permitting affirmative action first established in the 1978 case of University of California v. Bakke and reaffirmed as recently as 2016 in Fisher v. University of Texas. In those decisions, justices wrote that race and ethnicity could be used as one of many factors in admissions because schools have a "compelling interest" in the educational benefits of a diverse student body. That legal standard, alongside the ratification of the 14th Amendment in 1868, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and other progressive landmarks, are the underpinnings of what make any laws that provide a preference or special consideration on the basis of race permissible.

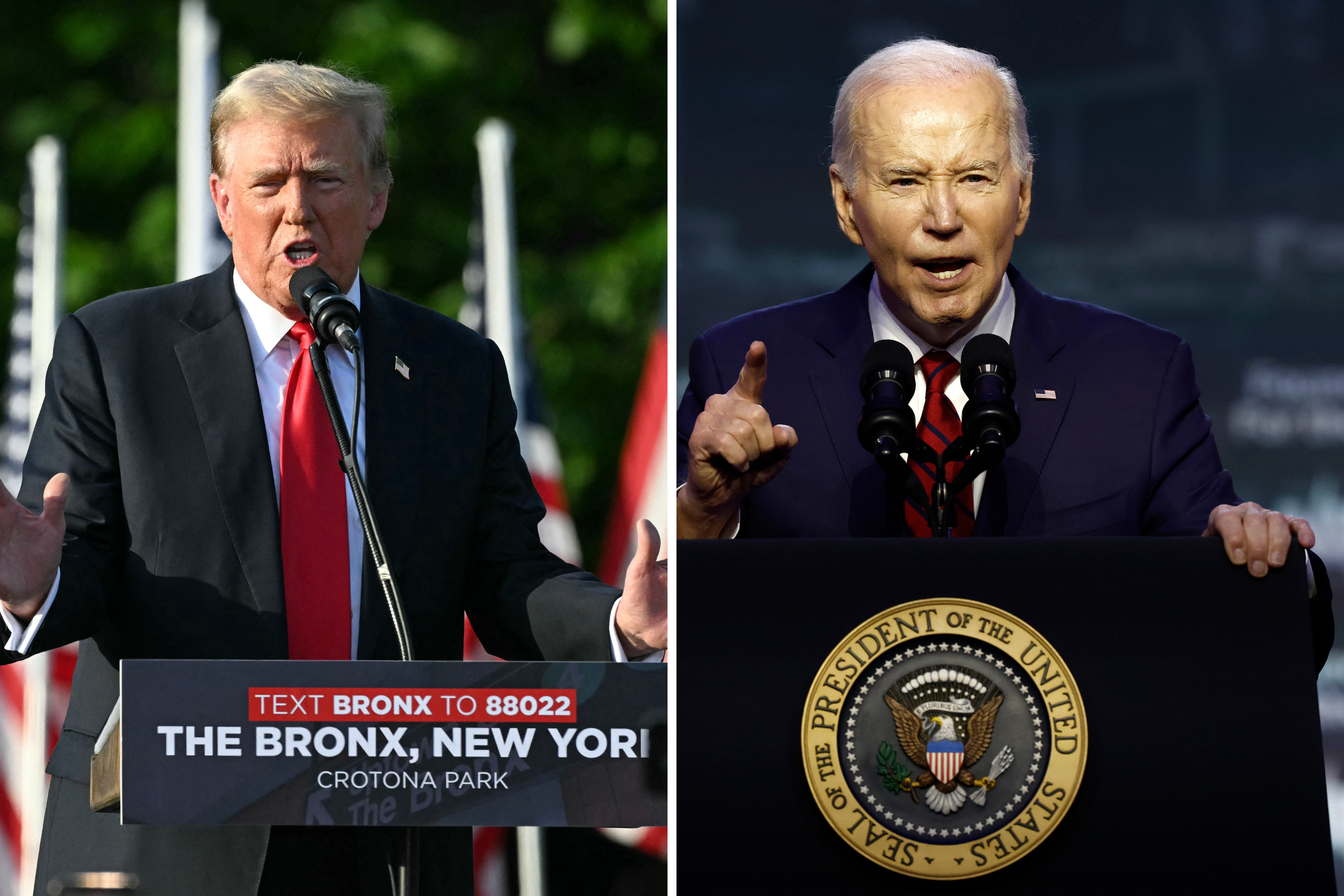

Since 2016, though, the court's makeup has shifted dramatically to the right with the additions of Justices Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, all appointed by former President Donald Trump. A newly emboldened 6-3 conservative supermajority earlier this year showed its willingness—eagerness, even—to overturn another key landmark of American life, the right to abortion set forth in Roe v. Wade in 1973. Affirmative action looks likely to be the court's encore to that ruling.

In taking up twin cases in which an anti-affirmative action group called Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) has sued a public school, the University of North Carolina (UNC), and a private one, Harvard University, the court appears ready to bar colleges from giving any weight to an applicant's race. Both cases allege the schools illegally discriminated against white and Asian applicants, who tend as groups to score better on tests and attend better high schools, by giving special preference to applicants who are Black, Hispanic and Native American.

At one point during a Harvard attorney's insistence during oral argument about the importance of a racially diverse campus to students of all races, Justice Clarence Thomas said, "I've heard the word diversity quite a few times, and I don't have a clue what it means. It seems to mean everything for everyone." Justice Samuel Alito, too, wondered what the term "underrepresented minority" means. And both Justice Barrett and Chief Justice John Roberts demanded defenders of affirmative action put an end date on when its goals would be achieved. Lawyers for the universities could not do so with any specificity.

The cases hinge on how the court now interprets perhaps its most hallowed decision, the 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, which required desegregation in public schools and accommodations by deciding that the doctrine of "separate but equal" was unconstitutional. Lawyers for SFFA argued in a brief that Brown requires education "be made available to all on equal terms," thus implying that any preferences violate the Constitution. Attorneys for UNC responded that schools working to diversify their overwhelmingly white student populations "are the rightful heirs to Brown's legacy."

"I didn't hear anything in the arguments or the questioning from those jurists that made me think there should be something to be hopeful about," says Alvin Tillery Jr., a political science professor at Northwestern and director of its Center for the Study of Diversity and Democracy. "The same people, when they win this, they'll start suing companies for their supplier diversity programs, suing cities for programs that help minority businesses, suing to remove everything that acknowledges and seeks to help people of color."

Or, as University of Maryland education professor Julie J. Park puts it: "It's just going to be an earthquake."

'Who's Real About This'

Ground zero for that earthquake will be offices like that of Matt McGann, director of undergraduate admissions at Amherst College. The tiny liberal arts school in central Massachusetts is known as one of the most racially diverse elite colleges—49 percent of attendees identify as students of color—and that, McGann says, is because of the ability to "consider all of the things that make the applicant an individual and all of the things that they would bring to our campus community." The school does not use racial quotas or give a specific weight to race in considering applicants, McGann says, but his team's approach does tend to arrive at more diverse classes than many other elite schools.

McGann, who waited overnight in line at the Supreme Court to be able to sit in its tiny gallery for part of the hearings, is now convinced that his job is about to get significantly more difficult. For instance, during oral arguments, justices asked the lawyers for SFFA whether they believed a student should be prohibited from writing about their race in application essays; the SFFA lawyers said that would be fine.

McGann predicts that would produce great confusion and uncertainty. "If a student writes about their experiences of race in America or if they tell us that they're the president of the Native American students association or if they tell us that they go to church at an African Methodist Church, how do we approach those things?" he asks. "We'll be waiting for details to try to best understand what a decision will mean beyond just who wins and who loses."

Any way the eventual ruling is written, though, McGann and others seem resigned to the prospect that, at the very least, they may not be able to even ask about race on applications, a common practice since 2010 when the Education Department under President Barack Obama mandated all colleges and universities collect data on race and ethnicity. Losing that information, affirmative action advocates say, will make it more difficult to know if an application should be given any preference. (Most colleges and universities in the U.S. don't rely on affirmative action because competition for admissions isn't that fierce. More than half of four-year institutions accept more than two-thirds of the students who apply; only 70 are selective enough that they admit fewer than 25 percent of applicants.)

McGann's fear is that Amherst will go the way of the University of Michigan and University of California at Berkeley, two top public schools that were forced to abandon race-conscious admissions preferences after voters in those states passed referenda barring the practice. The share of Black and Latino students at UC Berkeley fell by 50 percent immediately after the anti-affirmative action measure took effect; at Michigan, the share of Black students fell 44 percent and of Native American students by 90 percent after a 2006 ballot measure passed.

Both schools have sought a wide range of approaches to recruitment that have helped their minority populations rise, but they haven't come close to their pre-ban figures. The entire University of California system, which—in addition to Berkeley—also used affirmative action for its other highly selective schools in San Diego and Los Angeles, has spent more than $500 million over the past quarter century to market to and offer financial aid to students based on what their ZIP codes suggest about their economic status and racial composition. The aim is to drive up application rates among those groups and, thus, accept more of them, says Olufemi Ogundele, UC Berkeley's dean of undergraduate admissions.

"Do I think we've figured it out? I don't, not really," Ogundele says. "For institutions that value diversity, with a tool of affirmative action going away, it's going to be a question of how does an institution show its values for diversity and inclusion? Oftentimes, diversity is just an agenda item. The day is coming when we'll find out who's real about this."

Stacy Hawkins, vice dean of Rutgers Law School and a senior fellow at the Institute for the Study of Global Racial Justice, disagrees: "I can't imagine any college or university or employer who is currently explicitly committed to diversity, after the Supreme Court says, 'Oh, you shouldn't be valuing this,' saying 'I guess we can't value it anymore.' No, they're going to value diversity, and they're just going to figure out how to do it in spite of what the court says."

Abandoning the SAT and Legacies

In addition to the intensive efforts modeled by Berkeley, diversity proponents are eyeing other reforms and legal avenues to improve the chances of minority applicants. One increasingly popular approach is to go "test-optional," disregarding or not asking for an applicant's scores on the SAT or ACT. Northwestern's Tillery says schools have been moving past those longtime standardized exams because they are "a terrible predictor of student performance." Wealthier students can take private preparatory classes that lead to high scores but don't necessarily reflect their typical academic abilities, he says.

"The SAT gap is really about wealth and income gaps that track with race," Tillery says. "It's not that Asians are super geniuses and that's why they have higher scores. It's that they have more affluent families than Black or Latinx families and even more than the white families, and they are preparing for the test in ways that require money."

Yet dropping the SAT has not proven to be a panacea, Amherst's McGann says. Amherst is in the third year of a four-year test-optional experiment prompted by the fact that it was unsafe for students to take the tests in person at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Applications have surged 40 percent to about 14,000, but the largest increases came not from disadvantaged American students of color but international students and white Americans, McGann says. "Do I think that test-optional can help us to continue to achieve our diversity mission? To some degree, yes. But I don't know that it has had a very significant impact so far."

Another possibility that came up several times during the October 31 Supreme Court hearing was whether legacy admissions—giving preference to students whose parents or grandparents attended the school—amounts to giving white students a racial advantage. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson asked SFFA attorneys whether Black students whose parents or grandparents could not have gone to an elite school when it was segregated are at an disadvantage when competing against white applicants.

"If this is about making the process racially neutral or fair, the only way to do that would be either identity blindness, which no one seems to want, or by striking down alumni preferences, which some studies have shown are actually more impactful than considering race as a plus factor," Tillery says. "That's a very easy, logical extension of this argument. And I think it's going to happen."

Post Affirmative Action America

Just as Brown v. Board of Education resulted in the desegregation of more than just public schools, legal experts say, the affirmative action cases the court is considering now are bound to set a new precedent that calls into question any place in American life where laws or policies protect, boost or deny people based on racial representation.

"One of the things the court does is plant little time bombs that will explode later on," Howard's Powell says. "Today, we're ostensibly talking about education. But there is a spillover effect, for example, in government contract set-asides for minority businesses [because] they exclude whites who want to participate. It's an example of reverse discrimination. So we need to review and overturn all public contracts. Same thing with employment. A white plaintiff says, 'Well, yeah, I didn't get the job. You're considering race and that's reverse discrimination.' I see a whole onslaught of more emboldened plaintiffs articulating reverse discrimination claims."

There'll also be a certain amount of excess caution on the parts of private businesses and public entities that, say, provide scholarships exclusively to specific racial groups. Requiring attendance at diversity sensitivity trainings, too, could become legally fraught.

"There will be negative repercussions for things like financial aid and for scholarships that are given out with a race-conscious component to them," the University of Maryland's Park says. Park and a colleague studied the impact of affirmative action bans in the nine states that have them, she says, and found that those prohibitions had "a chilling effect on whether administrators felt free and comfortable talking about race at all. They were very worried about being sued, so they played it safe and actually probably went overboard."

Whether the Supreme Court goes as far in scrubbing race preferences from American life as so many legal experts predict remains, of course, an open question until a decision comes down. That's expected in late June, when the court tends to release its most consequential and controversial decisions.

While the consensus among affirmative action advocates is gloomy, there are a few optimists among those who listened to the October 31 hearing. The back and forth between the justices and lawyers about whether students could discuss racial experiences in their essays, for example, suggests that even opponents of race-conscious admissions policies accept that race can affect a student's outlook and approach to the college life.

Natasha K. Warikoo, a Tufts University sociologist and author of Is Affirmative Action Fair? The Myth of Equity in College Admissions, says, "Do I think that there's going to be a narrowing of affirmative action? Yes. Is it possible that they're going to say that any consideration of race is never allowed? That's possible. But I also think it's possible there will be something in between. They seem to understand that race is a part of a person's lived experience. So I think that there is room for something less than a completely color-blind society."

Similarly, Anne Meehan, a lobbyist for the American Council on Education, was heartened by the fact that hearings scheduled for two hours took five and by some questions posed by "some of the newer members of the court, really wrestling with the complexity of the issues here."

"The discussion showed the justices weighing all the nuance and complexity around this issue," says Meehan, whose group represents 1,700 colleges and universities. "It is still quite possible that consideration of race in admissions could be preserved in some meaningful fashion. We'll have to wait and see. That's the hard part, waiting till June."

***

Action, Reaction: An Affirmative Action Timeline

1961

The term is believed to be coined in an executive order signed by President John F. Kennedy dictating companies that receive federal funds "take affirmative action" to ensure they don't discriminate in hiring on the basis of race.

1964

President Lyndon Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act banning discrimination based on race, color, religion or national origin.

1964

President Lyndon Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act banning discrimination based on race, color, religion or national origin.

1969

President Richard Nixon launches a test project in Philadelphia requiring the construction industry make plans to "meet the goals of increasing minority employment."

1978

In Regents of University of California v. Bakke, the Supreme Court strikes down a quota system designed to set aside spaces for minority and poor students but upholds the ability of schools to consider race in admissions on grounds that diversity is a legitimate interest in education.

1995

President Bill Clinton calls for an end to any program that "(a) creates a quota; (b) creates preferences for unqualified individuals; (c) creates reverse discrimination; or (d) continues even after its equal opportunity purposes have been achieved."

1996

California voters pass Proposition 209 requiring the state not "discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin in the operation of public employment, public education, or public contracting."

2003

The Supreme Court rules in Grutter v. Bollinger that the University of Michigan's law school could use race as one of many factors in selecting applicants. But in Gratz v. Bollinger, the court finds the university's use of race as a factor in a system that assigned points to evaluate applicants was not constitutional because it did not provide "individual consideration." In her majority opinion in Grutter, Justice Sandra Day O'Connor writes, the "Court expects that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today."

2006

Michigan voters approve a constitutional amendment banning consideration of race, sex or religion for admission to publicly funded colleges and other institutions.

2013

In Fisher v. University of Texas, the Supreme Court upholds the use of race as a factor in admissions but requires the school prove to a federal judge that "available, workable race-neutral alternatives do not suffice." A federal appeals court approves UT's plan the following year.

2014

In Schuette v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action, the Supreme Court upholds the Michigan constitutional amendment approved by voters in 2006 banning affirmative action.

2016

In Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, the Court again upholds the constitutionality of affirmative action.

2022

A conservative Supreme Court majority, bolstered by three new justices appointed by President Donald Trump, hears oral arguments in two cases contesting the constitutionality of the consideration of race in college admissions.