A crisp line of five black SUVs pulled up in front of the refugee safehouse in Pakistan's capital of Islamabad around 5:30 p.m. on Oct. 10, 2021.

The 260 Afghan residents of the safehouse looked on as more than 20 armed men from the State Department's Diplomatic Security Services streamed from the vehicles, entered the building and lined up, weapons in hand, creating a human corridor.

The Afghans had all been expecting to be evacuated.

But the security forces had only come for the "high-priority package:" President Joe Biden's one-time Afghan interpreter and his family.

After Aman Khalili and six of his family were rushed to the SUVs, more than 200 of the Afghans surged into the street, throwing rocks at the cars, blocking them with their bodies and begging to be taken as well.

The SUVs drove off without them.

"We tried to question why they were just taking Aman and his family," said Faiza, the pseudonym for a 55-year-old woman who traveled from Afghanistan with the Khalili family and her own. "But no one replied."

Ten months later, Faiza and most of the other 260 Afghans remain in hiding in Pakistan. All had worked in support of the U.S. during the 20-year war or were religious and ethnic minorities.

Their sense of betrayal over what they see as a broken promise by the Biden administration is emblematic not only of last year's disorderly U.S. evacuation of Afghanistan, but of the way American support has quickly evaporated for Afghan allies, according to the groups trying to help them.

As news headlines have shifted from the chaotic U.S. pullout in the face of the Taliban on August 30, 2021, they remain abandoned - except for the thousands of veterans and civilian volunteers who say they're standing by allies who fought for the same cause.

"If we are everything we claim to be as a country and we promote these values ... we damn sure need to have a plan both for an orderly withdrawal, but then also making sure we get the right people that we've been working with out," said David Hicks, a retired U.S. Air Force brigadier general, who founded the non-profit Operation Sacred Promise to support and evacuate Afghan allies. He was not familiar nor involved with the Islamabad incident.

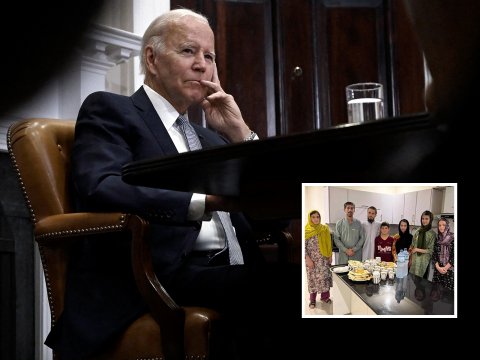

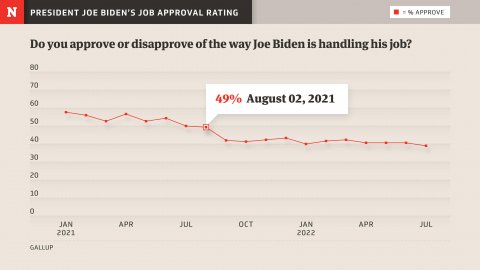

Khalili's rescue was heralded at the time by the White House. It was one seemingly positive story after months of damaging news from Afghanistan and sinking poll ratings for Biden - who has never recovered from a drop in popularity that accelerated with the exit last August.

Newsweek has pieced together details of what happened to the refugees who were left behind when Khalili was rescued.

"They promised to do everything they could. Did they? No," said Safi Rauf, president and founder of the Human First Coalition, the NGO that ran the safehouse and got Khalili into Pakistan.

"These are people who put their lives on the line and stood shoulder to shoulder with us on the frontlines to help our soldiers, our military in Afghanistan," Rauf told Newsweek.

The U.S. expedited the visa process for Khalili and granted his family special waivers because they did not have passports, he said.

Rauf says the State Department broke a verbal promise to come back to evacuate the 260 remaining refugees from the safehouse. Two other sources said that had also been their understanding of the situation, but another said that there was no specific promise. Nothing was written down.

The White House and State Department did not respond to multiple requests for comment to determine whether a promise was made, or what debt, if any, President Biden believes he owes Afghan allies left behind.

With resources dwindling, the safehouse was shut at the end of May and the 200 remaining Afghans were dispersed among other safehouses. The former head of daily operations at the safehouse said rescuing only Khalili and his family was "very unjust." Speaking on condition of anonymity for safety reasons because he still lives in Pakistan, he said: "It was a media stunt for the U.S. to save face."

Sarah Teske, a retired Marine who helped the Human First Coalition with moving Khalili and the larger group out of Afghanistan, says she took over paying to feed and house the remaining Afghans with money from a grant she received from a nonprofit after the safehouse closed. As of September, that money will be gone, she said.

"It should not be on veterans and donors and private funders to help these people," she said. "Department of State and White House could step in today to solve this."

Newsweek was unable to locate Khalili for comment on the fate of his fellow refugees.

The Worsening Problem

Being left behind was devastating, said Faiza, a health care worker for 15 years. She had supported women and children, including through USAID-funded programs, according to documentation provided to Newsweek.

Now, almost a year later, she and the rest of the group are still living in fear and hoping to be evacuated.

They are among the estimated 200,000-plus allies left behind, mostly in Afghanistan or Pakistan.

But now the safety net to evacuate and protect the Afghan allies is starting to fray. All this, just as winter is approaching, and with it, the promise that Afghanistan will face one of the greatest humanitarian crises of modern times, according to the U.N. Development Program.

"We've used all of our personal resources, all of our savings, everything we've had, we have used it, and we have nothing left," Rauf said.

The Human First Coalition is one of an estimated 200 civilian- and veteran-led groups that have emerged over the past 12 months to fill the vacuum left behind when the U.S. left Afghanistan. The groups try to help feed, support and even evacuate Afghan allies eligible for a legal path to the United States. Their resources are dwindling.

"Once Ukraine was invaded, it became so bad on the fundraising side that we had to close out almost all of our safehouses," said Ben Owen, an Army veteran and founder of Flanders Fields, another nonprofit that has been supporting and evacuating Afghan allies. He said that his organization went from 68 safehouses to eight in just 30 days.

Most of these groups said they relied on donations from private individuals and small foundations. Last September, some donors were even issuing "seven-figure donations" via wire transfers, said Tom Amenta, a U.S. Special Operations veteran who is also co-writing a Georgetown University research report on the civilian evacuation of Afghan allies.

The U.S. has spent $775 million since August 2021 on humanitarian assistance for Afghans, including those in neighboring countries, the State Department says. By comparison, it spent more than $1.5 billion on humanitarian aid for Ukraine between February and July, USAID said. It has also committed more than $13.5 billion in security assistance to Ukraine, since January 2021, the Department of Defense said.

The Numbers

Many volunteers in the networks believe Ukrainian refugees are getting a smoother path to the U.S. as well as more aid.

Of the 8,000 Afghan Humanitarian Parole applications processed since July 2021, only 123 were approved, according to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services data obtained and released this month by the Reveal/Center for Investigative Reporting. The program is for people with urgent humanitarian needs, such as those receiving death threats from the Taliban.

The Humanitarian Parole program for Ukrainians started in April. By Aug. 4, USCIS had approved more than 68,000 of the 97,000 Ukrainian applications, according to the report.

While Afghans were required to pay $575 per person, the Ukrainians were spared fees. USCIS has collected nearly $20 million from 66,000 Afghan applicants seeking Humanitarian Parole since July 2021, according to Reveal/CIR.

The difference is partially due to the Humanitarian Parole program only allowing applicants two years in the U.S. - which is ideal for many Ukrainians who hope to return to their home country, but not necessarily for the many Afghans seeking to start a new and permanent life in America.

Beyond that, just 8,000 Special Immigrant Visas for Afghans were processed and completed from September 2021 to August 2022 - averaging 725 per month, according to an August 2022 report by the Association of Wartime Allies, a nonprofit advocacy group.

There's at least a remaining 74,000 Afghan allies who have SIV applications in process, state officials said.

White House and State Department officials said that "substantial" efforts have been made to speed the Afghan SIV application process.

"We continue to process SIV and refugee applications daily ... We have increased the number of staff working on SIV processing by more than fifteen-fold," a State Department official said.

There are also an estimated 22,000 people who have other pathways to the U.S. through referral visa systems designed for people who didn't work directly with the U.S. military or government, but on related programs, according to a source familiar with the administration's Afghanistan evacuation and resettlement efforts.

It also doesn't include the people who have pending applications for Humanitarian Parole.

Why This Afghan?

That is the tangled bureaucracy and desperate fate that Khalili escaped.

He was briefly Biden's interpreter for one mission in 2008 as part of a team that rescued the then-senator from Delaware when his helicopter was caught in a heavy snowstorm in Afghanistan. His story of being left behind broke last August, adding to the negative press for the Biden administration.

Khalili had cachet that the other 260 allies did not, said Rauf, who started the Human First Coalition last August with just his phone and his laptop, but soon attracted partners who helped the organization grow to support 10,000 people at the height of operations.

As pressure mounted on Biden following a story published by the Wall Street Journal at the end of August, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki pledged that the U.S. would assist Khalili.

"Our commitment is enduring, not just to American citizens, but to our Afghan partners who have fought by our side," Psaki told a news conference last September. "We will get you out."

The White House and State Department sped the processing of Khalili's Special Immigrant Visa after it was reported that he had been caught up in bureaucracy.

In the meantime, the U.S. couldn't physically move the family out of Afghanistan.

The solution: Get help from an NGO that could get Khalili out via its connections on the ground.

That was Rauf's organization.

Rauf says it was during conversations on getting Khalili out of Afghanistan that a promise was made to help the other 260 Afghans - though he has no written evidence.

Teske and Rauf said they believe the Khalili extraction was a public relations move.

Teske also believes there was a U.S. promise to rescue the Afghans. Teske said it was apparent based on emails she exchanged with State Department officials regarding a proposed flight manifest for the larger group.

A senior Congressional staffer also said he was on a call in which State Department officials promised Rauf that they would return for the rest of the group.

But Alex Plitsas, COO of the Human First Coalition, said the promise was not so clear.

"State Department officials I spoke with said they would do all they could to help but couldn't promise that it would happen," he told Newsweek. "Ultimately, the manifest was not approved, as the individuals were not eligible for immediate entry into the U.S. immigration system," said Plitsas, a U.S. Army Special Operations combat veteran.

Rauf says the U.S. government could have found a way to help - adding that it was only because Khalili was accompanied by other Afghans that he was able to leave Afghanistan safely. The Taliban would have been more suspicious of a family traveling alone, Rauf said.

Khalili's family were accompanied on the arduous three-day journey by 60 other people, who were among those at the safehouse.

A State Department official who worked on Afghan evacuation efforts said the situation was far from unique.

"There were countless SIV-qualified families who were used to mask high-value targets (and) who were later left behind, despite assurances they would be rescued," the State Department official said, speaking to Newsweek on condition of anonymity because the person was not authorized to comment on the subject.

Faiza, her husband, their children and a brother and sister-in-law were among the 60 who traveled with Khalili and helped to cover his escape from Afghanistan.

"Our lives are just as important as Aman Khalili's and his family's," Faiza said.

"Our services are just as vital as theirs ... Why are certain individuals treated differently than others?" she said, with her son translating from Germany via encrypted messages.

Faiza's husband died a few months ago of a heart attack.

The group at the safehouse included people who had worked directly with the U.S. government such as interpreters and Afghan military personnel, according to records provided to Newsweek. There were also women judges, women's rights activists, journalists, religious minorities and World Food Program managers.

Of the group, 136 had passports; 42 had applied for Special Immigrant Visas or had documentation they were eligible; eight had referrals for a special process known as the P1 visa, and at least 89 were pursuing other routes, including Humanitarian Parole, according to a copy of a manifest that the coalition had created when it expected State Department help with evacuation.

Like Khalili, all would have required some kind of special accommodation, expedited processing, or a waiver and assistance to get out of Pakistan.

The White House, National Security Counsel and State Department did not respond to questions about any accommodations or exceptions made for Khalili and his family.

A 'High Priority Package'

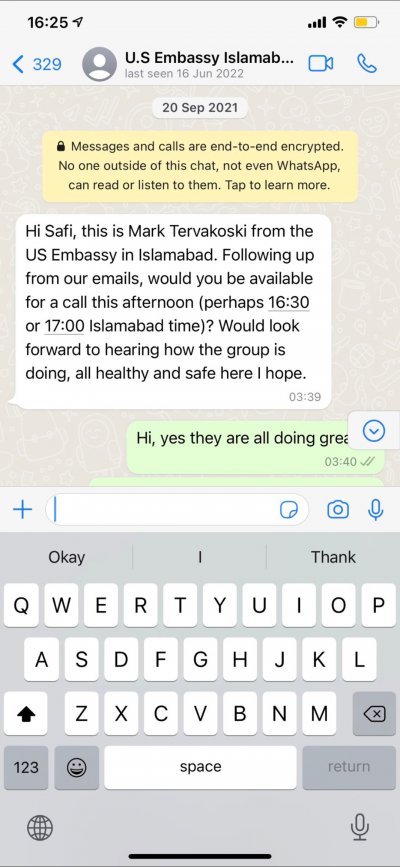

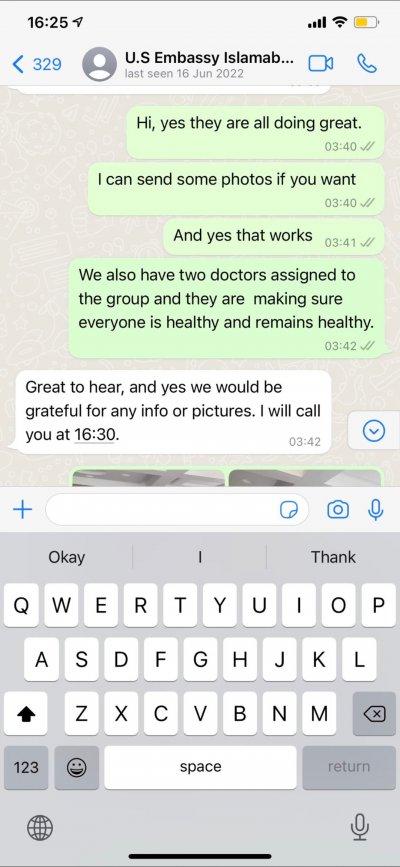

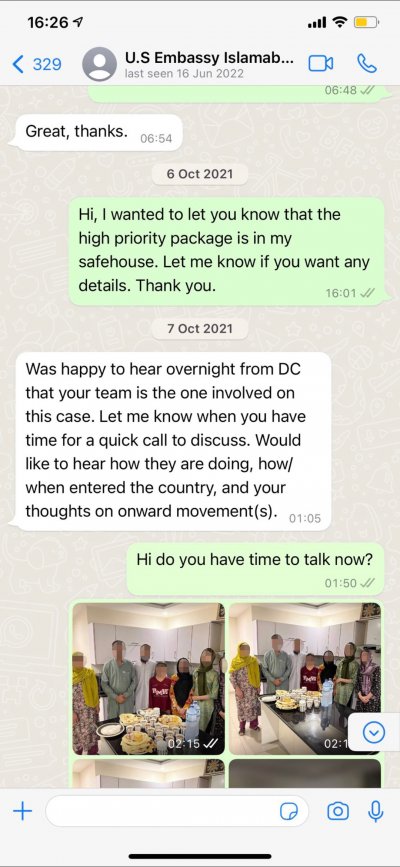

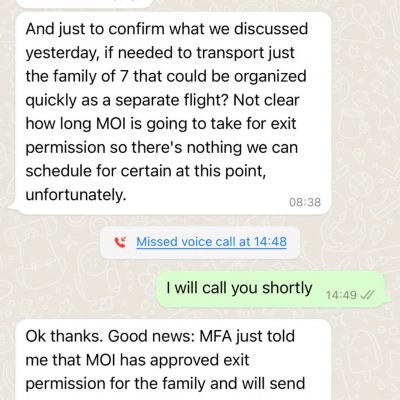

Ahead of the mission to remove Khalili, Mark Tervakoski, then the Afghanistan Task Force director at the U.S. Embassy in Islamabad, messaged Rauf on Sept. 20, 2021, asking about the welfare of a larger group of Afghan refugees who arrived at the safehouse before Biden's interpreter, according to screenshots obtained by Newsweek.

On Oct. 6, Rauf notified Tervakoski that the "high priority package" - Khalili - was in the safehouse, according to a text message. On Oct. 9, Tervakoski messaged Rauf related to Khalili: "Washington (at high levels) is asking what options there are to fly the family out ASAP. Welcome your thoughts on how to do this for just the 7?" Tervakoski said.

Rauf said he believed the State Department had already made a promise, so he reminded Embassy and State Department officials by phone about the 260 others in the safehouse.

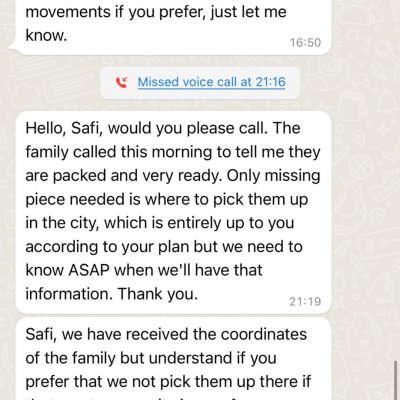

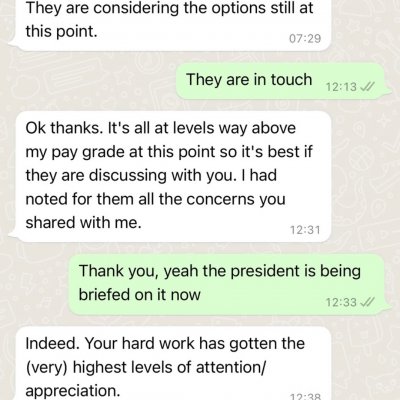

By Oct. 10, Tervakoski said in a message that Washington was "considering the options still at this point," and that he had relayed Rauf's concerns to Washington, saying things were "above my pay grade at this point."

Rauf messaged Tervakoski to say "Washington" has been in touch, adding that President Biden was "being briefed on it now."

Rauf told Newsweek that a senior officer at the State Department notified him that the president was looped in, but declined to name the person on the record.

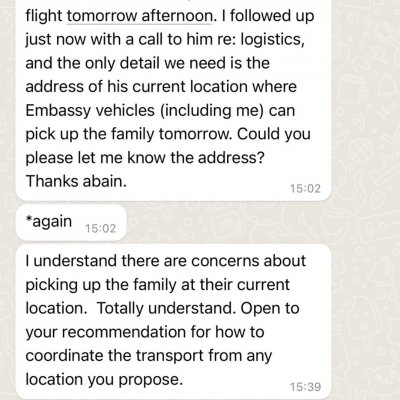

Tervakoski then asked for the location of the safehouse so the family could be removed alone. Rauf did not provide that information.

Rauf said he told Tervakoski removing only the Khalili family was "going to create a huge problem, especially for all the people that are there" in the safehouse.

"I was like, 'Well, you can't just take him because there's other people and ... they're going to have opposition to it - and they're not going to be nice about it," Rauf said he told Tervakoski.

The White House and State Department did not respond to specific questions about what transpired.

"Safi, we have received the coordinates of the family but understand if you prefer that we not pick them up there (at the safehouse) if that creates security issues for your other travelers," Tervokoski wrote later on Oct. 10. "Please advise or we will have to proceed only on the location info we have. As you can understand, the Embassy also has to do advance security planning for all vehicle movements within Pakistan so time is of the essence."

He added that the Embassy had "a small passenger bus with regular (non-diplomatic) plates that we would use for pickup so as not to attract attention."

Rauf did not respond. Hours later the SUVs turned up at the safehouse.

By Oct. 11, the White House had a new story to tell the WSJ. Its headline: "Afghan Interpreter Who Helped Rescue Joe Biden in 2008 Escapes Afghanistan; After a personal plea to the U.S. president, weeks in hiding and a clandestine evacuation, Aman Khalili gets out with his family."

Rauf, 28, is an Afghan-American who was born in a refugee camp in Pakistan, immigrated to the U.S. as a teenager and later enlisted in the U.S. Navy Reserve.

He has his own reasons to be grateful to the Biden administration: It helped negotiate his release after he was captured by the Taliban on a humanitarian mission to Afghanistan last December and was held for 105 days of "incredibly difficult" captivity.

But Rauf says he will not let up in pushing the administration to rescue the Afghans left behind.

Promise or No Promise

In fact, "there wasn't a written explicit promise" made to the majority of Afghan allies, said Hicks, the retired Air Force brigadier general. "It's more about the inferred promise."

The route to the United States has begun to look even harder for allies left behind.

Many have had their visas expire as they waited in hiding. Others had their passports destroyed by American officials at the U.S. embassy, according to an email from the State Department to an SIV applicant, obtained by Newsweek.

"This action was taken to prevent these sensitive documents from being captured by third parties," the email said.

America's apparent abandonment of its allies will not help its global reputation, said Akbar Ahmed, a professor of the School of International Service at American University.

"There's a sense that America is a good friend when they need you, but when they don't need you, they pack up and leave," Ahmed told Newsweek.

Moving allies to the United States in a large-scale, vetted and organized fashion would be the best way to save lives, said Matt Zeller, an Afghanistan veteran and co-founder of the No One Left Behind evacuation group

"The only person who can do something about that is the president," he said. "It's a matter of life and death."

For Faiza and the others who watched Khalili's evacuation as they were left behind, the sense of betrayal is very personal.

"We deserve better," Faiza said. "We have the right to live and be protected. Our children deserve a better life and a brighter future. We aided your forces while risking our lives."