All summer long, Joe Biden surrogates in Pennsylvania lived in fear of a rerun of 2016's Nightmare on Election Night, when the Democratic candidate for president, after leading in the polls for weeks, lost the state to Donald Trump by less than one percentage point, clearing his path to the White House. Their biggest concern was tactical: By avoiding in-person campaigning during the pandemic, Biden insiders worried that the former VP was ceding a big advantage to Trump, who, coronavirus be damned, was holding boisterous rallies across the Keystone State and, by proxy, knocking on millions of doors, just as he'd successfully done four years before. Fast forward to early fall, though, and suddenly Biden was everywhere—on a tour of western Pennsylvania with whistle stops in Pittsburgh, Latrobe, Greensburg and Johnstown; delivering a unity speech in Gettysburg; meeting with business and labor leaders in Erie; and authorizing door-to-door canvassing to drum up support and get out the vote, not just in PA but across other battleground states as well.

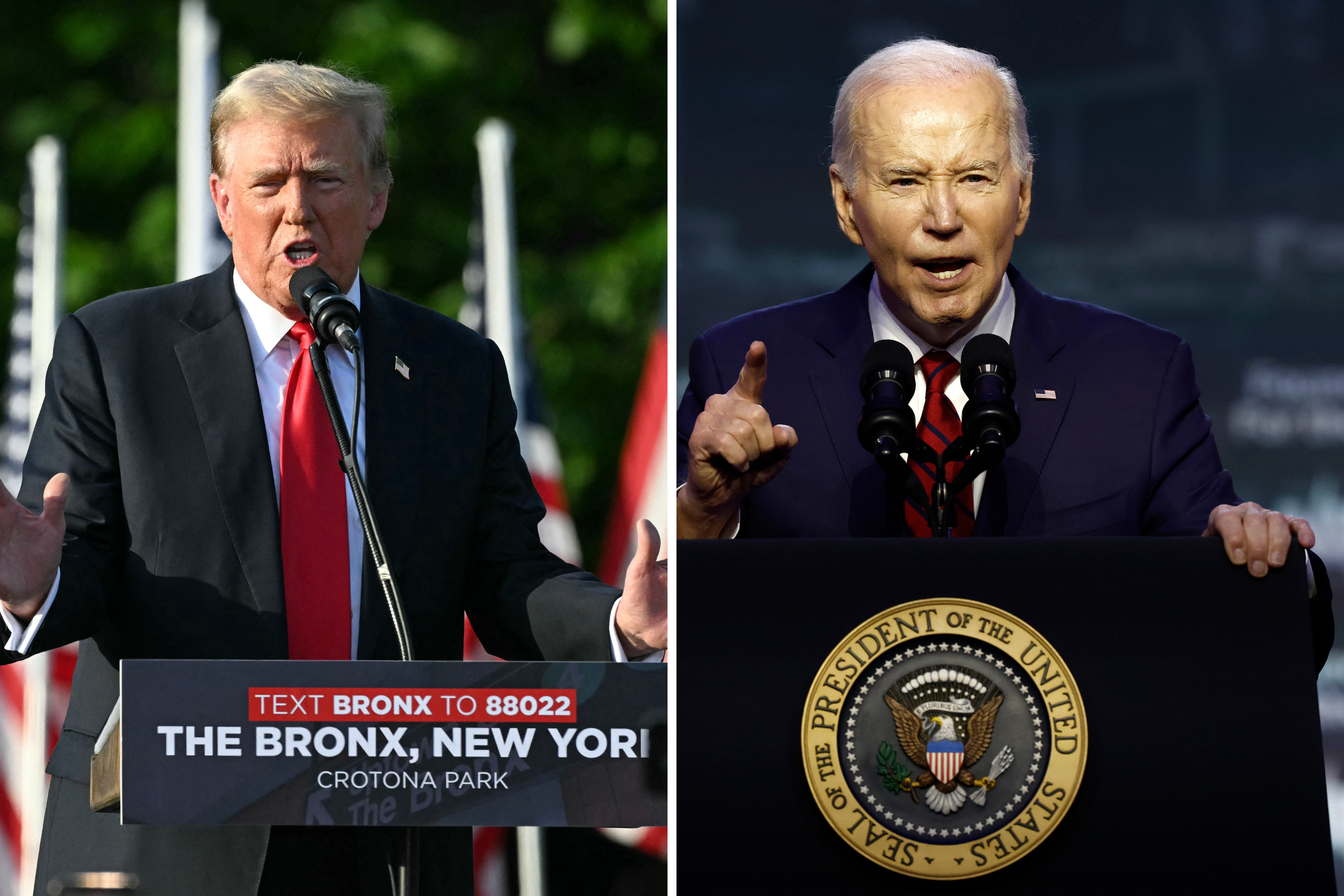

What convinced "Basement Biden," as Trump mockingly refers to his opponent, to so dramatically reverse course—ironically, just before the president was forced by his COVID-19 diagnosis to pull back from the campaign trail?

In a word, Pennsylvania.

The tipping point, sources within the campaign say, was a September 26 ABC News/Washington Post poll showing much softer support among the state's Biden voters than among those backing Trump. Echoing the campaign's own disquieting internal data, the survey found that, despite an overall nine-point lead for the former VP, only 51 percent of Biden backers were "very enthusiastic" about their candidate vs. 71 percent of those who supported Trump. That "rang the alarm," a top Biden insider says.

"Pennsylvania is driving everyone's strategy," the source tells Newsweek. "We can't leave any tactic off the table." The insider adds, "We'll probably win here. But if we don't, we are so screwed."

The outsized political influence of Pennsylvania is partly pure math: The state's 20 electoral votes are must-haves in almost every likely path to the necessary 270 for either Trump or Biden. The website FiveThirtyEight, which uses statistical analysis to forecast outcomes, calls it "the single most important state of the 2020 election," and the likeliest to provide the decisive vote in the Electoral College. The site's modeling gives Trump an 84 percent chance of remaining in the White House if Pennsylvania goes red and estimates there's a 96 percent chance of a new occupant—at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, mind you—if the state flips to blue instead.

The numbers game, though, is only part of the story. The composition of the state also makes it a reasonable stand-in for the American electorate writ large, all jammed into one vast geographic rectangle. It has a nearly even mix of non-Hispanic white voters without college degrees (particularly in the heartland) and more diverse and educated voters (particularly in and around Pittsburgh and Philadelphia). It also has a large number of high tech and healthcare professionals as well as blue-collar workers, once likely to toil in the coal or steel industries and now often employed in natural gas production.

"Pennsylvania is this microcosm of the nation where Democratic support has become more and more concentrated in highly populated areas and Republican support is becoming concentrated in less populated areas," says David O'Connell, a political science professor at Dickinson College in Carlisle, in the south central part of the state. "The outcome [here] will determine the fate of the nation itself."

It's not exactly surprising then that, with less than four weeks to go before voting ends, both candidates are amping up efforts and strategizing fiercely to map out the road to victory in Pennsylvania. For Biden that means heeding the lessons from Hillary Clinton's losing campaign in 2016 and, in some respects, doing the opposite. For Trump, on the other hand, it's more of the same—to the extent that he can follow the same path amid a pandemic. Meanwhile, legal challenges to the voting process by both parties (but especially Republicans) mean that Pennsylvania could lead the nation in another way: as a symbol of election chaos in an already-turbulent year.

The Trump Way in PA

If there is any doubt about how seriously the Republican ticket is taking messaging in Pennsylvania, consider how often they talk about fracking—a topic bound to resonate in a state that is the nation's second largest producer of natural gas (after Texas).

Less than a day after returning to the White House following his hospitalization, Trump took a moment during a particularly hectic tweet storm to ponder and predict: "How does Biden lead in Pennsylvania Polls when he is against Fracking (JOBS!), 2nd Amendment and Religion? Fake Polls. I will win Pennsylvania." The next day, during the debate, Vice President Mike Pence hit hard on fracking as well, insisting his predecessor as VP wants to ban the practice, even though Biden has explicitly said otherwise. The following day, Trump was back on the frack attack, tweeting: "The Great Commonwealth of Pennsylvania would absolutely die without the jobs and dollars brought in by Fracking. Massive numbers! Now Biden & Harris, after Radical Left Dem Primaries, are trying to change their stance."

Speaking to Pennsylvania voters in struggling rural and industrial regions of the state, many of them lifelong Democrats who felt ignored and degraded by their party, was critical to the surprise Republican win in 2016. Trump spent his first campaign crisscrossing those areas, blasting both parties for international trade deals that had brought misery upon manufacturing and agriculture and promising Pennsylvanians he would bring back steel mills and coal production, protect the natural gas industry from environmental regulations and improve the fortunes of farmers.

It worked. While Clinton led in and around Philadelphia and Pittsburgh on Election Day, exit polling showed Trump won rural and ex-urban voters by 71 to 26 percent, with 63 of the state's 67 counties voting Republican by wider margins in 2016 than they had in 2012.

Trump's strategy for 2020 is to continue doing what worked four years ago, only with better organization and hundreds of additional field organizers. The campaign frequently brags about its canvassing prowess—1 million door knocks a week, it says, although there's no way to verify that—and claims to have held more than 4,000 meet-ups involving some 38,000 people. Until COVID sidelined him, Trump made personal appearances as well, visiting Pennsylvania 24 times as president—the most to a state where he doesn't own a golf resort or a presidential retreat like Camp David—including three rallies in September in crowded airport hangars in Pittsburgh, Harrisburg and Latrobe.

The state's Republican Party has benefitted too, says RealClearPolitics editor Charles McElwee, who oversees Pennsylvania coverage. As of September, every county with fewer than 100,000 voters has more registered Republicans compared to 2016. Democrats still maintain a nearly 800,000-voter statewide edge, but that lead is down more than 16 percent from four years ago.

"The enthusiasm is greater in 2020 for the Republicans than it was in 2016," says Lisa Buckiso, chair of a subcommittee of Pittsburgh's Allegheny County Republican Party. "It's going to be a close race in Pennsylvania."

That's not exactly what recent polls show. The latest RealClearPolitics survey of state polls has Trump down by an average of 7.1 points, vs. just 3.2 percentage points a month ago. But Buckiso isn't buying it: "So many polls were wrong in 2016. You still have those secret Trump voters who won't say they're supporting the president but when it comes to Election Day, they'll pull that lever."

The campaign's TV game reflects the strategic decision to pan for votes in every region and among every demographic. For the rural and small-town voter who came to Trump's side in 2016, there's a garage owner in Scranton, Biden's hometown, who attests, "Until COVID hit, Trump had the economy booming" and "Jen," a fracking technician who warns about the damage Biden's less gung-ho stance on the practice could inflict. For suburbanites, Trump stokes fear of racial unrest by painting Biden as pro-rioting and anti-police. "Joe Biden empowers these people," says one cop, referring to Black Lives Matter demonstrators. "The more you empower them, the more crimes they go to commit." And, in a gambit to peel away some Black voters, Trump is also airing a spot with retired NFL player Jack Brewer warning: "Joe Biden's America was mass incarcerating black men. President Trump set them free."

Still, the bread and butter is the same as 2016. "How the Republicans are going to win is to further increase their margins in rural and ex-urban Pennsylvania while holding down their losses in various suburbs," says GOP strategist Christopher Nicholas. "It remains to be seen if they can."

Biden: Not Trump. Or Hillary.

Biden has also been paying attention to Pennsylvania from the start of his run. In 2019, he gave the first speech of his third bid for the Democratic nomination at a union hall in Pittsburgh, saying, "I came here because, quite frankly folks, if I'm going to be able to beat Donald Trump in 2020, it's going to happen here."

Biden's Pennsylvania campaign director Brendan McPhillips insists the lack of in-person campaigning until recently and the decision not to set up traditional field offices has not hobbled the cause. In a mid-September memo laying out the campaign's endgame, McPhillips noted staffers and volunteers had made phone calls and sent text messages to nearly 5 million prospective voters over the prior three months. He also suggested the 44,000 votes that Clinton lost by in 2016 could easily be found in the Philadelphia suburbs where anti-Trump sentiment was so high that Democrats flipped three House seats in 2018. And the campaign made clear it has no intention of ceding small towns as Clinton did, maintaining it has "held over 250 events and engaged 140,000 supporters in rural areas that voted for Trump in 2016."

The central lesson: "We aren't taking a single Pennsylvanian for granted."

In an interview with Newsweek, McPhillips elaborated. "We're making a real, intentional effort to go everywhere and talk to everyone, including campaign stops in deep red counties where for a long time Democrats have struggled," he says. "We believe we can win back a lot of those voters by just having an honest conversation and giving them the respect of asking for their vote. We're not going to win all the time, but we will close the margins and it's going to be a difference-maker."

Biden echoed that sentiment during his post-debate whistle-stop tour. "Look, a lot of people around here voted for Donald Trump last time. I get it," said Biden, standing in front of a massive CAT rig at a training center for heavy machinery in New Alexandria, after picking up the endorsement of the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners and the International Union of Operating Engineers. "I've been asked many times in recent years, 'How did we get to a place where the people who teach our kids, take care of our sick, build our bridges, operate our trains, who race into the burning buildings and don't ask who's in there, people who, in fact grow our foods, how do we get to a place where they think we don't see them or hear them or respect them?' Well I see 'em. I hear 'em. I respect 'em. I know 'em. They're family. It's gonna change. It's gonna change with me."

Biden, unlike Clinton or Trump, also cultivated ties with the state's union and industry leaders over his 36-year Senate career representing neighboring Delaware, and was sometimes referred to as Pennsylvania's third senator. "There's a real comfort level talking to Joe Biden," says Bobby "Mac" McAuliffe, Pennsylvania director of the United Steel Workers, which endorsed the Democrat at that first campaign stop in 2019. "He understand our issues. Donald Trump appealed to some of our members by talking about tariffs and about how that would revitalize the steel industry. But we saw so many jobs still that went overseas."

"Pennsylvania is looking like a lot of other states where Trump is underperforming among whites who have a college degree, among women, among seniors and in the suburbs," says O'Connell, the Dickinson professor. "That's a lot of who live in those counties in the Philadelphia region, which makes up about 20 percent of the state population. It's not enough to win, but if Biden runs up huge margins there, more so than Clinton did, it's going to be very tough for Trump."

The Biden campaign has mounted an aggressive advertising effort in Pennsylvania, spending $27 million between April and mid-September, which is more than double the Trump spend, according to Kantar/CMAG, a market research firm that collects data on TV buys. For the final six weeks before Election Day, Trump had reserved $11.5 million to Biden's $10.1 million in TV time for the state. Also playing are ads from the Lincoln Project, a group of Republicans supporting Biden, which spent $380,000 in Pittsburgh, Harrisburg, Erie and Philadelphia in September featuring L.A. Clippers coach Doc Rivers slamming Trump's attacks on demonstrators protesting police brutality against Blacks.

The upshot? Most observers think Biden's lead in the polls is more authentic than Clinton's was four years ago. Back then, O'Connell says, "State-level pollsters weren't weighting for education level, which turned out to be a predictor of individual votes, and weren't weighting for education because it wasn't as important until you saw this re-alignment of voters with college degrees towards Democrats. That will be remedied this time."

Legal Battles Looming

One measure of the primacy of Pennsylvania to both sides is the phalanxes of lawyers lining up to file suits over virtually every piece of the 2020 election process. Most of the challenges revolve around legalities regarding absentee voting in a year when registrars expect some 3 million mail-in ballots from voters who prefer not to risk contracting COVID at polling places on Election Day.

Already, the Democrats have lost a battle to count so-called "naked" ballots, or mail-in ballots that are not sheathed properly in the security envelope when they're returned. Meanwhile, the GOP lost a case in which the state's highest court ruled that county election boards can count mail-in ballots postmarked by November 3 that arrive by November 6. In yet another matter, Republicans are suing in federal court to overturn Pennsylvania Secretary of State Kathy Boockvar's decision to allow ballots to be counted even if signatures are inconsistent.

The legal attack on mail-in ballots is an extension of Trump's repeated false claims that they are subject to widespread fraud. "They're going to try to steal the election," Trump groused at his Harrisburg rally last month. "The only way they can win in Pennsylvania frankly is to cheat on the ballots." At the debate with Biden, he also brought up an incident in which a handful of military ballots were found in the garbage in Luzerne County and another in which Trump supporters were not permitted to be poll-watchers in a Philadelphia precinct. There isn't any evidence of illegality in either case, but he nonetheless memorably proclaimed that night: "Bad things happen in Philadelphia."

McPhillips says the Biden camp has "the largest voter protection team that a national campaign has ever had in the state" in anticipation of a flurry of lawsuits aimed at throwing ballots out in Democratic strongholds. Meanwhile, Buckiso wishes her party would focus more on encouraging mail-in voting than litigating over it. Of 2.4 million mail-in ballot requests in Pennsylvania through September, 66 percent came from Democrats versus 24 percent for Republicans.

Both sides say the public should brace for a slow count and no clear winner on November 3 due to the mountain of mail-in ballots that cannot be processed until polls open on Election Day. And if, as so many prognosticators believe, the fate of the presidency hinges on the Keystone State, the result of all this haranguing could be a protracted legal fight that keeps Americans in suspense.

"If it winds up being a decisive state, we've already had concerns raised about the ability of state election officials to administer this election," O'Connell says. "I worry about Pennsylvania in 2020 becoming Florida in 2000. What a mess that would be."

Steve Friess is a Newsweek contributor based in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Follow him on Twitter at @SteveFriess.