The COVID-19 pandemic has rapidly and radically disrupted any sense of normality in all aspects of medical practice in the United States. Rationing life-saving care is not something American doctors are accustomed to consciously consider in our daily working lives, let alone ever communicate to patients or their families. At most, we are taught a little about it, typically in school, as a part of a formal course in medical ethics.

At Harvard Medical School, where I have taught hundreds of students just such a curriculum for well over a decade, we spend a few hours on the subject in a classroom setting in their first year. In my experience, consensus rarely emerges, but many students settle most comfortably with some manner of utilitarian thinking—in the abstract, it intuitively makes sense that we ought to maximize the number of lives saved in a crisis.

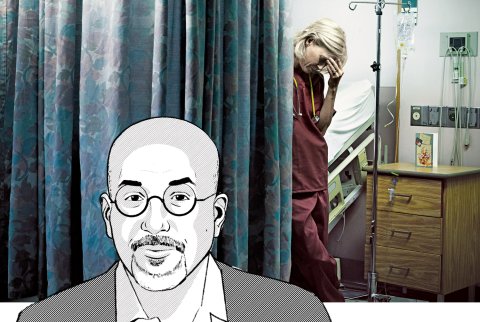

But the moral distance is immense between academic discussions and actually caring for sick people with names, faces and life stories. As soon as we are done, as students, discussing neatly constructed ethical arguments, we become residents, fellows and attending physicians, and we learn to singularly prioritize the breathing, speaking person in front of us.

We are quickly indoctrinated into the rule of rescue: save each patient with all means available. And, up until now in our country, the means have, by and large, been readily available. We have not needed to build up the psychological fortitude to confront genuinely life-threatening scarcity.

Conversations about death in an intensive care setting typically occur after we have exhausted all our therapeutic options. In my own practice, as a neonatal critical care specialist, there are times when we know that our baby patients are in the dying process despite our ongoing efforts to keep them alive. It usually isn't an abrupt change in clinical condition or some unexpected catastrophe that convinces us, but rather a relentless smoldering over days, weeks and sometimes even months. Artificially breathing for our patients, supplying powerful drugs to keep their hearts pumping and providing energy cocktails of sugar, protein and fat intravenously are not enough to stave off the inevitable. We might buy more time continuing our interventions, but the writing is on the wall.

When this clinical suspicion registers loudly enough, we feel more urgency to have the hardest conversations with parents. They need to at least hear, if not right away accept, that it is more likely than not that their baby will not survive—despite us trying everything in our bag of therapeutics to save their child.

That last bit is the key for our own sanity and to maintaining trust with our patients: that we have tried everything.

We are fortunate that most parents eventually come to terms with our clinical conclusion once it has been introduced. They are rarely naïve to what we are observing, even as they hold on to every last ounce of hope. Under the best of circumstances, our last few hours or days together are spent trying to allow for a dignified death that our little patient's families can live with, heartbreaking as it invariably will be. In my experience, most parents are grateful that their baby was given an honest chance at life in our hands.

I dare say in my NICU, utility rarely, if ever, enters our bedside ethical calculus.

The current pandemic demands that we doctors refashion ourselves in deeply uncomfortable robes. As an educator of medical students and postgraduate trainees, I am certain that most of my younger charges identify with Captain Kirk much more than Mr. Spock. Nor are most socially Darwinian by nature.

Our bioethicist friends are trying to soften the blow, recognizing our vulnerability to the rescue obsession. They recommend that these life-or death rationing decisions must be made before the patient ever meets our gaze—that institutional committees informed by rigorous ethical analysis dictate allocation protocols that best approximate what will be the "least-worst" set of outcomes.

I am sure this is wise in the long run. We need to admit that no rationing system of life-saving therapy is capable of satisfying all stakeholders, but a haphazard and opaque approach will devastate an essential social trust privileged almost exclusively to our profession. We must do our best to balance fairness and efficiency while ensuring transparency.

And yet, I still worry this exercise in applied ethics, while desperately important, can only do so much moral work. Yes, if all goes well, more lives will be saved in the end without grotesque, across-the-board discrimination against the feeble or aged. And, since every life is meant to have equal worth, the more saved, the better. Nevertheless, I also cannot help feel that a crucial part of our humanity will be chipped away each and every time such decisions are actually made.

We will not just suffer deep emotional trauma that might scar us for the remainder of our professional and personal lives, but also violate something basic to the calling of the healing professions. It may not be sacred, but I am not embarrassed to call it spiritual. These consequences count too.

Even if doctors and nurses are not making the call on who gets a ventilator, we will be the ones tasked to deliver inferior, if not straight away palliative, care. We will be the ones pronouncing our patients dead. It will be our faces, voices, arms and legs, not those of ethicists, hospital administrators or public health officials, that physically failed to provide them with an optimal chance at rescue.

There is no distancing us from the horror. The psychological toll on us should not be underestimated.

The families of these forsaken patients will not be grateful to us, nor should they be. They will have been wronged, period—no matter how crisply a philosophical argument might suggest otherwise. The psychological toll on them should not be underestimated.

So, during these days of reckoning, my humble plea is threefold: One, let's not discount this gravest of harms by sweeping it under the procedural cover of sterilized hospital protocols. Two, let's not be dismissive of the devastation to patients and their families who are passed over for the sake of prioritizing some human values over others. Lastly, let's take more than a mindful moment each time it happens to communally cry and curse out loud, and then further pause to recall that neither cool rationality nor dispassionate reason are all or even most of what actually makes us decent, caring health professionals.

I fear that if we do not, we will all be the lesser for it.

Sadath A. Sayeed, J.D., M.D., is assistant professor of global health and social medicine at Harvard Medical School.

The views expressed in this article are the writer's own.