Audrey Wu, a video editor at a Hong Kong TV station, was not even born in June of 1989, but her father has told her about what happened back then in Beijing. He told her of the demonstrations that began to honor the late Chinese leader, Hu Yaobang, a liberal reformer who had just died.

More and more students gathered at Tiananmen Square in the center of China's capital city, soon to be joined by workers and other ordinary Chinese citizens. The protests morphed, the demonstrators railed about inflation, and government corruption. Finally, the students erected a statue of Lady Liberty.

The uprising, from that point, became a call for democracy.

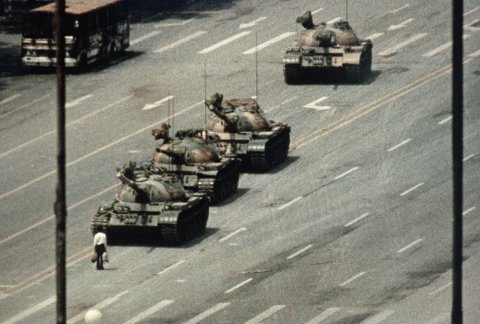

Wu knows what happened then, too. She knows the Chinese leadership had finally had enough. So they sent in tanks and soldiers, and the killing began. Wu, 27, knows all about the Tiananmen Square massacre.

Still, that hasn't stopped her from joining hundreds of thousands of fellow Hong Kong residents in the increasingly fraught demonstrations that have paralyzed the city for almost three months.

Those demonstrations ratcheted up considerably on August 12 and 13 when protesters occupied and shut down Hong Kong's international airport, one of the largest transit hubs in east Asia.

In response, a large unit of the People's Armed Police, based just over the border in the Chinese city of Shenzhen, began high profile drills clearly aimed at intimidation.

And a spokesman for Xi Jinping's government in Beijing issued a warning whose meaning could not be mistaken: the demonstrations had shown "sprouts of terrorism," which would be punished "without leniency [and] without mercy."

The threat brought the specter of Tiananmen to the fore; the occupation of the airport and Beijing's rhetoric got the outside world's attention, as U.S. and global equity markets plunged at the prospect of enduring chaos—or worse—in one of east Asia's financial hubs.

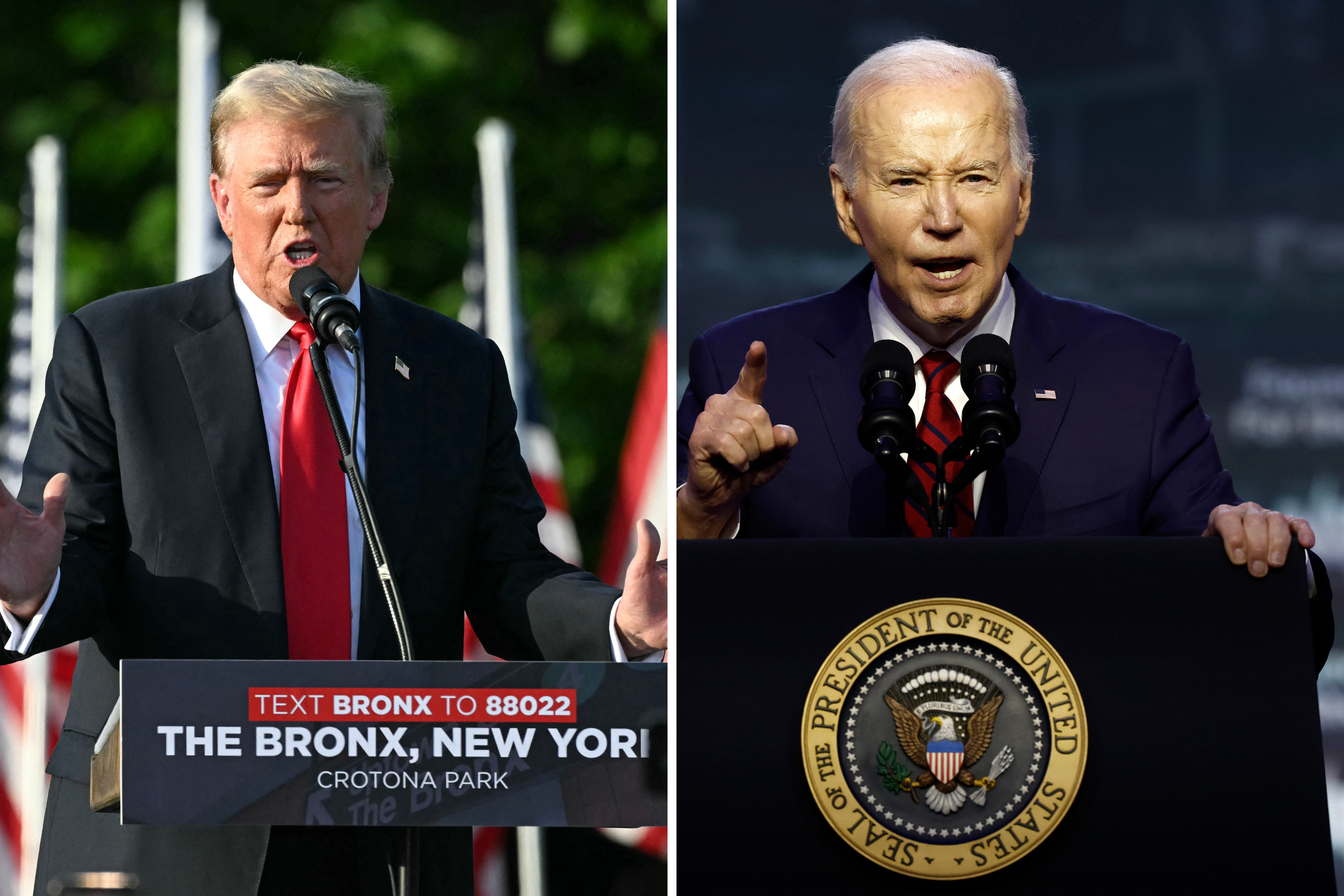

On August 14, President Donald Trump tweeted that he and Xi should meet in order to try and resolve the chaos—a ludicrous suggestion, given that Hong Kong is part of China.

"We may be seeing a tragedy unfolding again right before our eyes," said Stephen Roach, the former head of Morgan Stanley in Asia who lived for years in the former British colony. He added: "You just have to hope cooler heads prevail, but it's not yet clear that that will happen."

There were, in fact, echoes of the past in the way the demands of the Hong Kong protesters have shifted since first taking to the streets. The protests began in response to the introduction of legislation by Hong Kong's chief executive, Carrie Lam, that would have given extradition rights to Beijing for ostensible crimes committed by Hong Kong residents. Citizens rightly saw this as a fundamental breach of the 'one country two systems' pledge that undergird the 1997 handover of Hong Kong from Britain to China.

Beijing at the time agreed that Hong Kong could govern itself for the following 50 years. But both the letter and the spirit of that agreement have been fraying for years. In 2015, Beijing detained five Hong Kong booksellers whose shops sold gossipy books about Chinese leaders. One, 64- year-old Lam Wing-kee, was forced to confess his "crimes" on Chinese television. The extradition bill, for good reason, frightened many Hong Kongers.

But the protesters soon expanded their list of demands. Not only did they want the extradition bill killed—and it has only been shelved, for now anyway—but they wanted Chief Executive Lam to resign. They also wanted the government to retract its characterization of the demonstrations as "riots." Furthermore, they wanted an independent inquiry into the police's handling of the demonstrations. And now, they are calling for universal suffrage. (Even when Britain ruled Hong Kong, the city was never a democracy.)

There is no chance Beijing will allow that to happen. But the calculation as to how to respond now is very different than it was 30 years ago. The Tiananmen demonstrations were at the seat of Chinese power and almost literally on the doorstep of the Communist Party leadership. As Henry Kissinger and many others have since pointed out, the notion that the CCP was going to stand down in the face of that kind of unrest was always fanciful. There may have been ways, scholars have long argued, other than the vicious crackdown that ultimately ensued, to handle the situation. But an outbreak of representative government was never going to happen.

Now, the stakes for the Chinese leadership, while high, may not be as high as they were then. And the outside world does not seem to grasp this: that Hong Kong's importance to Beijing is not now what it used to be. Hong Kong was the outside world's primary window into China, then a gateway into the country, as well as its key financial hub, not subject to the tight leash that the leadership keeps on the Chinese financial system. (Under the one country, two systems rubric, capital still flows freely in and out of Hong Kong, while the government imposes strict capital controls on the rest of China.)

But inevitably Shanghai is emerging as the true financial capital of China, and foreign banks are beginning to see signs of liberalization that will allow them to compete in the mainland, and eventually ignore Hong Kong. Hong Kongers have long overestimated the importance their little city state—as attractive and alluring as it is. Back in the pre-handover, Deng Xiaoping era, there was a standard joke among Beijing-based China correspondents: when Deng wakes up in the morning, what's the first thing he doesn't think about? Answer, obviously: "Hong Kong."

Xi, though no doubt frustrated by the continuing demonstrations—the recent rhetoric about "terrorism" gives that away—probably doesn't want to give Hong Kong the back of his hand. A clumsy crackdown that evokes Tiananmen, he has to know, would be a disaster for Beijing. Xi is in the process of staring down Donald Trump in the ongoing trade war with the U.S., and Trump's picking of economic fights with other regions, from Mexico and Canada to the EU, has dissuaded U.S. allies from rallying to Washington's side against Beijing.

That would no doubt change if there were to be bloodshed in a place so familiar to tourists and businesspeople the world over. Xi and the leadership must know that his problems—economic and geopolitical—would deepen substantially if the outside world were to be revulsed by China-led clashes in Hong Kong.

He has raised the stick, but he can't want to use it.

More than 120,000 Hong Kong residents turned out on August 17 and 18, two of the biggest protests thus far. They were entirely peaceful, and served to keep the pressure on the Hong Kong government and Beijing to end the ongoing tumult peacefully.

But one of the issues for both Beijing and the Hong Kong government is that there have been no real leadership figures on behalf of the demonstrators to emerge as yet. In Beijing 30 years ago, many analysts believe, the original leaders of the Tiananmen demonstration lost control of what they had started.

Today it's not clear who, if anyone, has any control over the protesters. If a small group stepped up and made clear they'd talk to the other side, that could conceivably lower the temperature a bit. The Hong Kong government could agree to an independent commission to investigate the police, or some other step that might slow the protests' dangerous momentum.

Audrey Wu says she "can't imagine" Beijing "wants another Tiananmen square," and she's certainly right about that. But that doesn't mean it won't happen. The only thing clear: It wouldn't serve either side—or the world—for the turmoil to continue.