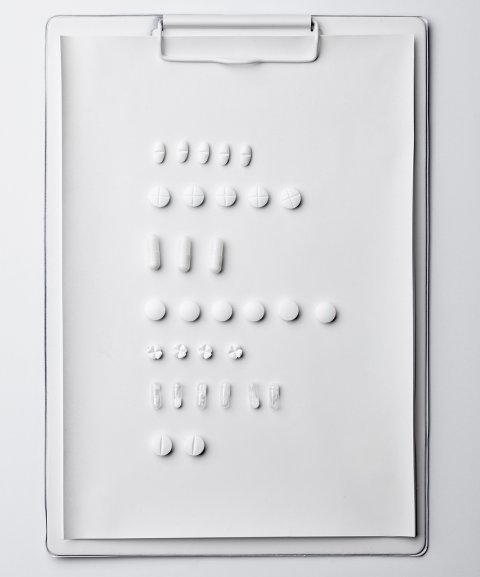

A New York Times bestseller published in May, Katherine Eban's expose shines new light on the mysterious generic drug manufacturing business. Almost 90 percent of America's prescription drugs are generics, with the majority of them made overseas. Fraud is widespread, Eban writes, in order to circumvent inspections and maximize profits. FDA oversight has been, to be kind, uneven, she says. Over the past year alone, for example, there have been recalls of dozens of batches of blood pressure medication, including two last month. A number of problems—impure ingredients, infestations of birds and flies, faked sterility testing—can be traced to India, which manufactures 40 percent of generic drugs dispensed in the U.S. The following excerpt describes the successful FDA inspection pilot program that was instituted in India in 2014, and was inexplicably halted the following year, Eban says—leaving the health of American consumers at the mercy of unscrupulous companies.

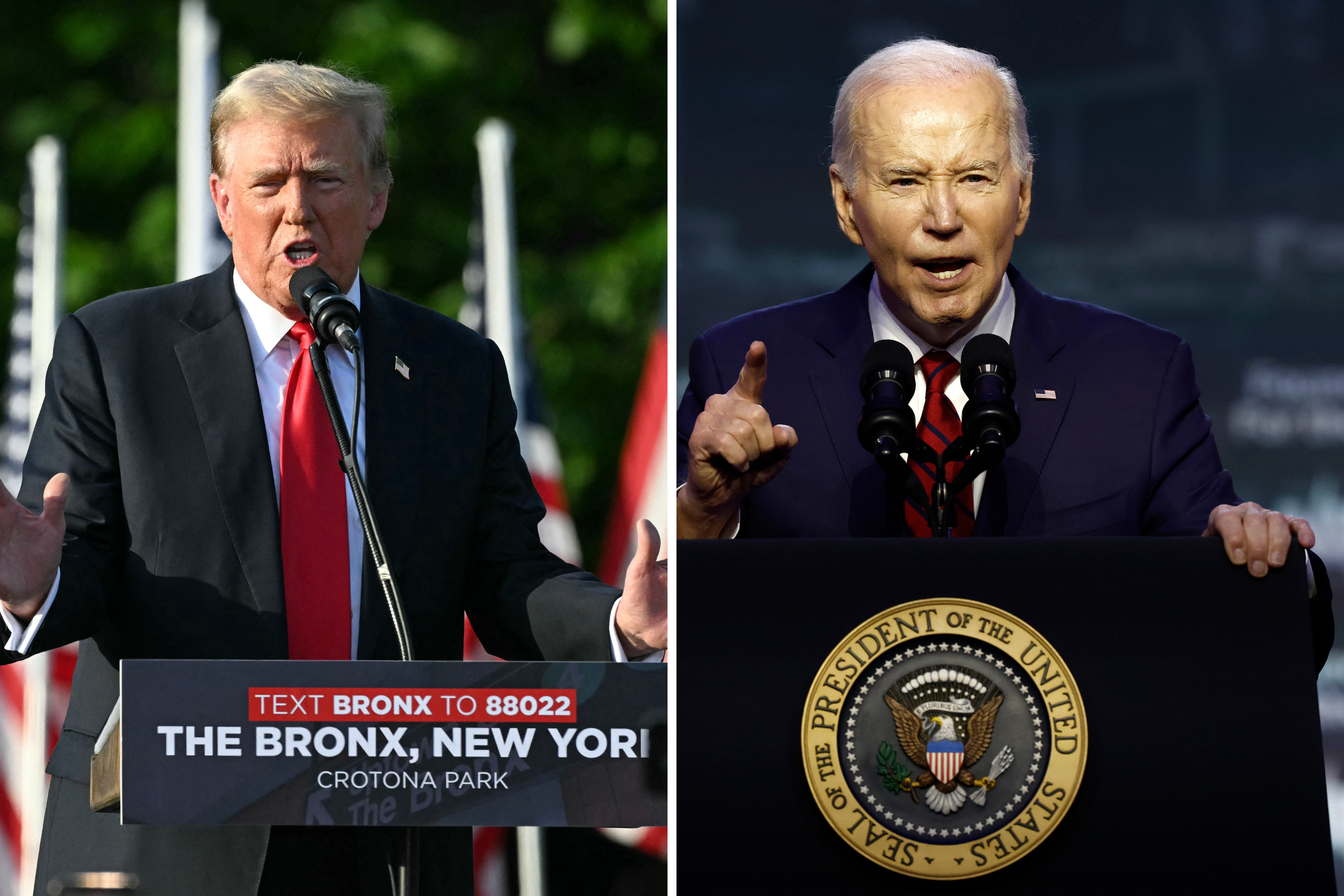

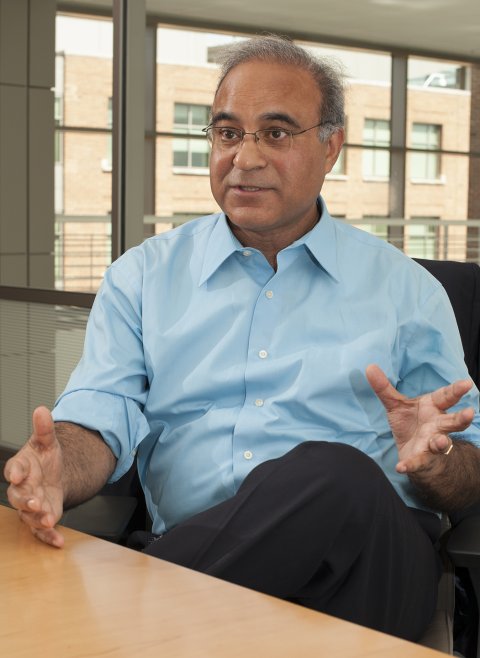

In June 2013, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration tapped Altaf Lal, an American of Indian origin with sterling public-health credentials, to solve what appeared to be a diplomacy problem. The FDA's relations with Indian regulators were in tatters, one month after India's largest drug company, Ranbaxy, pleaded guilty to seven felonies related to falsifying quality data for generic drugs it was selling in the United States. Ranbaxy seemed to stand alone as an overseas drug company that had broken U.S. laws and flouted critical regulations.

Lal, the newly-appointed head of the FDA's India office, outlined three goals in an agency blogpost: to establish a trusting relationship with Indian regulators; to conduct "prompt and thorough inspections" at the manufacturing plants that made drugs for the U.S. market; and to help Indian "industry and regulators understand that protecting the quality, safety and effectiveness of every product is essential."

In India, the stakes could not be higher for American consumers. Forty percent of all generics dispensed to Americans are manufactured in India. Many of the manufacturing facilities are aseptic plants, which means they have to operate with perfect sterility, and they provide finished doses—completed capsules, pills and tablets—to American patients. The U.S. and Indian governments needed to work together to ensure product safety: the United States was India's biggest pharmaceutical customer, and India was one of its biggest suppliers.

But in New Delhi, Lal found not just a diplomacy problem, but a public-health crisis in the making. The FDA was relying on a toothless system of pre-announced inspections that was allowing drug plants to stage inspections. "You guys must be in La La Land," is how one Indian pharma executive summed up for Lal the FDA's performance in India to date. In short order, Lal launched a transformative but controversial inspection program that exposed just how badly U.S. regulators were being hoodwinked.

Today, the U.S. drug supply is 90 percent generic, with the majority of these low-cost drugs manufactured overseas. Eighty percent of the active ingredients for all our drugs, whether brand or generic, are manufactured abroad, predominantly in China and India. The transformation of America's drug supply from domestic to global took place over two decades. By 2005, the FDA had more drug plants to inspect abroad than it did within U.S. borders. In theory, the result was a win-win for foreign drug makers and American consumers alike. The former gained entry to the U.S. pharmaceutical market, the world's largest and most profitable. In return, the American public got access to affordable versions of lifesaving drugs.

But a string of troubling revelations about the quality of foreign-made generic medicine has sharpened public concern. Generic drugs with toxic impurities, unapproved ingredients and dangerous particulates, or that are not bioequivalent to the brand, have reached American patients. Over the last year, dozens of versions of the generic blood pressure drugs valsartan, losartan and irbesartan have been subject to sweeping recalls, after it was discovered that some of the foreign-made active ingredients contained a probable carcinogen. The FDA contends that it maintains "global vigilance" and that its "standards and inspections for generic manufacturers are the same around the globe." Any drug manufacturer that wants to sell into the U.S. market has to submit to regular inspections and comply with the intensive regulations known as "current good manufacturing practices."

But in India, Lal learned that some drug manufacturing plants were choosing not to follow the regulations, in part because they had learned how to game the inspection system. In the U.S., FDA investigators show up unannounced at manufacturing plants. But for overseas inspections—due to complex logistics of visas and access to the plant—the FDA typically gives weeks or months of advance notice, allowing companies to fabricate critical aspects of their operations. The plants had drafted "internal memorandums and records directing employees to create falsified records in preparation for FDA regulatory inspections," Lal wrote back to senior officials at the FDA's Maryland headquarters.

As part of the pre-announced inspections, the FDA also relied on the companies to arrange on-the-ground logistics. At some of the plants, the hotels acted as surveillance operations. The hotel staff shared the investigators' itineraries quickly throughout the tightly wired manufacturing industry, with executives across companies communicating secretly through a chat group on WhatsApp. The companies also organized shopping trips, golf outings and trips to the Taj Mahal for visiting FDA investigators. This system of "regulatory tourism" as Lal saw it, had left the FDA investigators "captive and compromised."

To clean up this swamp, Lal alighted on a long-overdue solution, which he pitched to officials at FDA headquarters: eliminate the months-long advance notice and company-arranged travel plans and give only short notice—or no notice—of investigators' arrival for all inspections in India. By December 2013, the FDA signed off on Lal's proposal, and Lal started what came to be known as the India pilot program. He directed a supervisory consumer safety officer, Atul Agrawal, to take over all communications for the FDA investigators coming from the United States so that the companies wouldn't know who was about to walk through their doors or when.

Agrawal even arranged the investigators' travel through the U.S. embassy instead of the FDA's India office, to bypass the office staff, who had been the source of leaks to the industry. The India pilot program, as conceived by Lal and implemented by Agrawal, would give the FDA the most candid look yet at what was happening inside Indian plants. It had no parallel anywhere in the world: India would be the only country, other than the United States, where FDA investigators would arrive without notice.

The program's first unannounced inspection was scheduled for a Monday in early January 2014. It was at a Ranbaxy-owned plant in Northern India that had been responsible for glass fragments found in millions of tablets of generic Lipitor. With its version of the cholesterol fighter, Ranbaxy had launched the biggest generic drug in U.S. history. Agrawal wanted the investigators to get the real picture of what was happening at the facility. Fearing that word of the planned Monday inspection had already leaked, Agrawal made plane reservations outside of the official FDA travel system and moved the inspection to Sunday morning instead.

In the early hours, two FDA investigators arrived at the quiet plant and proceeded swiftly to the quality control laboratory. In the lab, they were stunned to see a hive of activity. They found dozens of workers hunched over documents in preparation for the investigators' anticipated arrival the following day. On one desk, the investigators found a notebook listing all the documents the workers needed to forge in anticipation of their arrival. Workers were backdating stacks of partially completed forms—for employee training, laboratory analysis, cleaning records—that were supposed to have been filled out contemporaneously.

As higher-ups arrived and word got out that the men were from the FDA, workers frantically stuffed documents into desk drawers. By showing up unannounced, the FDA's investigators saw things they never would have otherwise: vials stuck in the back of drawers; a sample preparation room swarmed by flies because windows were stuck open with piles of trash directly outside—or, as the investigators noted in their final report, "flies TNTC" (too numerous to count). The inspection resulted in a warning letter and an embargo of the plant's drugs.

In theory, it shouldn't have mattered whether U.S. regulators announced their inspections in advance or not. Drug manufacturers are supposed to follow good manufacturing practices all the time. Well-run plants operate in a state of continuous regulatory readiness. Compliance isn't a part-time thing. As Lal said,"The regulations are non-negotiable. You can't have the month of January as your good manufacturing month."

But in India, the FDA's new inspection program exposed widespread malfeasance that had previously been hidden. By showing up unannounced, the investigators uncovered an entire machinery that had existed for years: one dedicated not to producing perfect drugs, but to producing perfect results. With advance notice and low-cost labor, the plants could make anything look like anything. "You give them a weekend, they'll put up a building," as one FDA investigator put it.

The investigators found a bird infestation at one sterile manufacturing site. At another, they found a facility's paperwork for its sterility testing in perfect order, ensuring that the plant's air, water and surfaces were free of microbial contamination. Yet the samples didn't exist. They were testing nothing. The entire laboratory was a fake.

Under Agrawal's direction, the investigators flagged violations at company after company, which resulted in a growing number of negative findings and warning letters. Under the India pilot program, the rate of inspections resulting in the FDA's most serious finding, Official Action Indicated, increased by almost 60 percent. The program succeeded in exposing endemic fraud and dire conditions in India's drug manufacturing plants. It allowed the FDA to punish errant companies and restrict the importation of their products. It seemed logical for the FDA to make unannounced inspections the norm in every country in the world manufacturing drugs for the U.S. market. But FDA bureaucrats faced a conflict. With the public outraged over rising brand-name drug prices, the FDA faced political pressure to approve more, not less, low-cost medicine.

In July 2015, the FDA abruptly ended the pilot program without explanation. Fourteen months later, at a meeting in New Delhi, FDA officials announced to senior Indian drug regulators, an industry lobbyist, and several Indian generic-drug executives that the FDA was officially returning to its system of advance notice for all routine inspections. When asked by a journalist several years later why the FDA had discontinued the unannounced inspections, an agency spokesperson responded only in a written statement, "After evaluation of the pilot a decision was made to discontinue the pilot."

By then, Altaf Lal had retired from the FDA. But he was left deeply troubled by his experience of heading the FDA's India office: "I see faces in the U.S. that consume these drugs. They're not just numbers to me."

→ Excerpt adapted from Bottle of Lies: The Inside Story of the Generic Drug Boom by Katherine Eban, published by Ecco.

________________________________

Q&A: Katherine Eban

by Meredith Wolf Schizer

How did you come up with the idea for your book?

In 2008, Joe Graedon of the NPR program, The People's Pharmacy, contacted me. Patients had been writing in with serious complaints about generic drugs that either didn't work or caused devastating side effects. Top officials at the FDA had insisted to him that the patients' reactions were psychosomatic. But Graedon felt something significant was wrong and urged me to look into the claims. My effort to answer a single question, what is wrong with the drugs, launched me into a decade-long reporting odyssey on four continents. Ultimately, I uncovered how generic-drug companies circumvented regulations and resorted to fraud.

What obstacles did you face and how did you overcome them?

As a journalist, exposing corruption in your own backyard is hard enough. But to do so in a foreign country is altogether harder. As a single journalist on a book deadline, I was confronting real limits on my time and resources. I hired talented journalists to help with on-the-ground reporting in India, China, Ghana, in the U.S. and elsewhere. But ultimately, it was confidential sources—some who approached me, and some who I convinced to help—who provided me with the internal documentation on which the book is based: roughly 20,000 internal FDA documents; and thousands of internal corporate records from several generic

drug companies.

How can you protect yourself when buying prescription medication?

Consumers need to pay attention to the manufacturer of the drug being dispensed. Does it seem to work correctly without troublesome side effects? On my website, I have outlined steps that consumers can take to protect themselves, to investigate their own drugs or to request a switch to a different manufacturer. For example, before you even pick up your prescription, you can call the drugstore or mail order pharmacy and ask who manufactures your medication. Research the company on the FDA and People's Pharmacy websites, and if you aren't happy with what you find, request a manufacturer change.

Are there specific manufacturers or countries that are more reliable and can you request medications from them?

The drug supply is truly global now, with most countries getting their low-cost drugs from Indian and Chinese manufacturers. Those companies routinely make drugs of differing quality, depending on the vigilance of regulators in countries importing the drugs. Often, U.S. tourists make the mistake of buying cheap pharmaceuticals in developing countries, thinking the drugs are the same but just at a bargain price. The safest route for American consumers is to stick with the U.S. regulated drug supply. They can request an authorized generic from their pharmacist—the version made with approval from the brand-name company, often using the same formulation—and sometimes manufactured in the same plant.

How does it feel to be a bestselling author?

Sometimes, I doubted whether I could actually complete a global book about a complex industry. So, getting across the finish line and onto the bestseller list has been incredibly rewarding. It's hard to know what kind of reporting and information will actually break through. But, apparently, readers really are up for a journey into the distant manufacturing plants where their drugs are made.

What's next in your life?

I've been saying for a long time that I would stop reporting on the pharmaceutical industry and turn my attention to other vital topics like climate change. But since the book came out, I have been contacted by whistle-blowers from all sides of the pharmaceutical industry, each with important stories to tell. So, we'll see where that information takes me.