Canada is generally America's quiet, polite, less dysfunctional neighbor to the north. Political and economic news from Saskatoon or Alberta generally doesn't register south of the border. But this week, Canadian business was front and center.

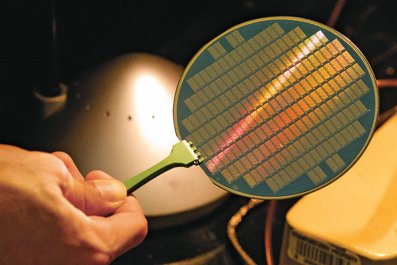

BlackBerry, the ailing communications-device maker based in Waterloo, Canada, has seemingly met its own Waterloo. A few years ago, when CrackBerrys were de rigueur in the corporate world, and its shares traded near $150, BlackBerry was on top of the world. But BlackBerry was rendered irrelevant by the advent of sleeker, more functional smartphones. After rounds of layoffs and losses, and with the stock down to single digits, the company was like a swimmer about to hurtle over Niagara Falls. Until a fellow Canadian threw the company a life preserver.

On Monday Prem Watsa, the chief executive officer of Fairfax Holdings, a Toronto-based investment and insurance firm, made a conditional offer to buy BlackBerry for $4.7 billion.

Watsa, 63, was born in India. After graduating from the prestigious Indian Institute of Technology, he came to Canada to get an M.B.A. and worked at insurance companies until he founded what ultimately became Fairfax Financial Holdings in 1985 in Toronto. Watsa has modeled himself after Warren Buffett, and Fairfax is often referred to as a smaller, Canadian version of Berkshire Hathaway, Buffett's investment vehicle. It's an insurance company that has used its cash flows and investments to acquire other insurance and financial-services companies—acquisitions this year include a pet insurance firm—and to make large financial bets. According to The Wall Street Journal, Fairfax netted $2 billion in gains betting against the U.S. housing market during the credit boom.

Like Buffett, Watsa writes lengthy letters to shareholders. But the comparison goes only so far. Watsa keeps a low public profile—it's rare to see him on CNBC or visiting with politicians in Ottawa. He doesn't like schmoozing with reporters. Over the years, his firm has also been attacked by short sellers who raised questions about the company's accounting and results. (The company struck back by filing a lawsuit against prominent hedge funds, including SAC Capital, charging them with spreading disinformation.) And Fairfax has weathered the storm. Its shares, which, like Berkshire Hathaway's, never split as they rose, trade at about $420 (Canadian), up more than fourfold in the past seven years.

BlackBerry's crisis has given Watsa an opportunity to act as a financial statesman of sorts. When he stepped down from BlackBerry's board of directors in August, speculation began that he might make a bid for the company. Purchasing a technology firm whose best days have passed is like catching a falling knife. But Fairfax has long held a significant stake in BlackBerry. And he may end up—should the transaction go through—purchasing a well-known brand at a relatively low price. In addition, Watsa would be salvaging what was until recently a great source of pride for Canada. Besides, like Buffett—and unlike so many technology investors—Watsa has an eye for the long haul. Last year he publicly mused about BlackBerry's prospects. "Is it going to turn around in three months, six months, nine months? No," he told reporters. "But if you're looking four, five years ... We make investments over four or five years."