Vladimir Putin may think he has trouble enough on Moscow's streets without worrying about demonstrators outside the country. If so, perhaps he should think again. This week in Istanbul, New York, Brussels, and other world cities, protesters are taking aim at his most cherished project: the 2014 Winter Olympics. Although the facilities at the Caucasus Mountains resort of Sochi are already winning enthusiastic praise from visiting skiers, thousands of angry activists are determined to spoil Putin's party.

The marchers are Circassians, the descendants of a people who once had their own country on the shores of the Black Sea, between Crimea and the modern-day Republic of Georgia. They lost it a century and a half ago to a brutal campaign by the imperial Russian army to seize the entire Caucasus region. The Circassians resisted for four decades until May 21, 1864, when they finally surrendered and were expelled from the land of their fathers. Until recently their descendants marked the date only with quiet remembrance ceremonies. But in 2007 the International Olympic Committee accepted Russia's bid to hold the 2014 Games at Sochi—the very place where the Circassians surrendered in 1864. Since then, May 21 has become a day of rage.

"How would you feel—how would the Russians feel, if athletes came from all over the world to ski or ice-skate on the graves of their ancestors—and [the athletes] did not even know they were doing it?" demands Danyal Merza. Last May 21, the 29-year-old telephone technician, along with two other ethnic Circassians, his friends Clara and Allan Kadkoy, traveled from their homes in New Jersey all the way to Turkey, where most members of the Circassian diaspora now live. The four of us ended up near the head of a chanting crowd of thousands of Circassians. The human wave, topped by a foam of anti-Sochi banners, poured down Istanbul's Istiklal Street before breaking against a triple line of police who stood with truncheons and tear gas outside the Russian consulate.

Speaking into a bullhorn, Merza squared his shoulders and shouted the group's demands in English: no Sochi Olympics, recognition of the Circassian genocide, and the right to move back to the homeland the Russians seized a century and a half ago. His listeners roared their approval in Turkish, and their voices resounded from the steep houses on either side: "We don't want Olympics in Sochi!" Allan pumped his fist and shouted along with them. "It's the first time I've chanted without knowing what the words mean," he told me afterward. His wife was similarly transported. "I could never imagine feeling like this," she said. "We might not speak Turkish, but we're all saying the same thing in different languages."

For Putin, being chosen to host the 2014 Games was a personal triumph. Sochi, where the forested Caucasus Mountains drop into the Black Sea and you can swim in the morning and ski in the afternoon, was to be the perfect venue to show the world that Russia had recovered from its post-Soviet problems. If there was any threat to the Sochi Games, security experts said, it would come from the opposite end of the mountains, in Chechnya. So when Circassian protesters turned up at the Vancouver Games in 2010, waving green-and-gold flags and demanding the Games be moved away from Sochi, most commentators were baffled. Circassians? Who were they?

A century and a half ago, people didn't have to ask. The Circassians were the world's favorite freedom fighters, the darlings of Western diplomats who viewed Russia's expansion as a threat to global stability. They battled for their homeland against almost impossible odds, holding out five years longer than even the Chechens had. And their defeat was catastrophic. Driven from their homes, they fled across the Black Sea to Turkey in dangerously overcrowded boats. No one was keeping count of the victims, but a contemporary historian estimated that 400,000 died, and almost half a million were deported. Only a relative handful were allowed to stay in Russia. And although their exodus was front-page news in the West, they soon slipped out of history, remembered only—if at all—as a source of concubines for the Sultan's harem. As far as I know, I am the only non-Circassian to have written a book about their tragedy, and that came out only in 2010.

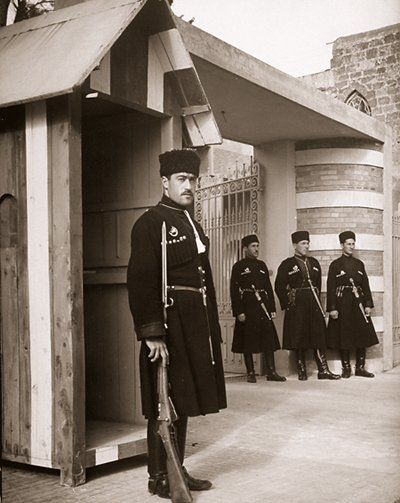

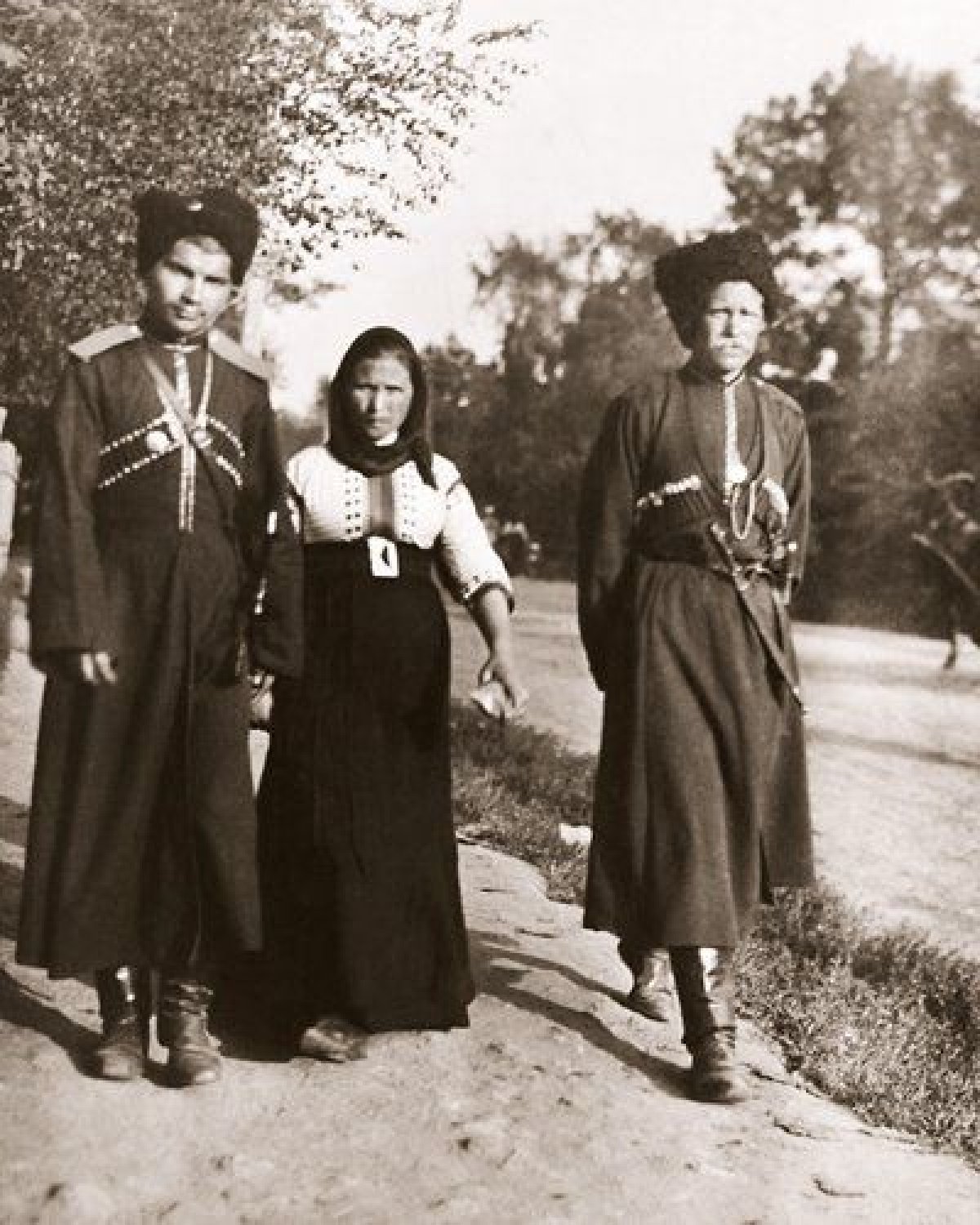

Documents from the time tell how the Russians loaded hundreds of thousands of Circassians onto sailing vessels and turned the evictees' abandoned homes over to the empire's shock forces, the Cossacks. One military report speaks of the crops that were left in the fields for the Cossacks to harvest and eat. My own research in the British archives has turned up letters describing the terrible conditions of the Circassian refugees. "Everywhere you meet with the sick, the dying, and the dead; on the thresholds of gates in front of shops, in the middle of streets, in the squares, in the gardens, at the foot of trees," wrote an Ottoman Empire health inspector from the town of Samsun, a place where 200 Circassians a day were dying in 1864, according to letters from the Russian consul at the time.

With the end of the Cold War and the rise of the Internet, Circassians began to piece together their history. In 2005 a Circassian activist and shopkeeper named Murat Berzegov asked the Russian Parliament to recognize the destruction of his nation as genocide. The request seemed reasonable enough: the legislators had previously acknowledged that Stalin's deportations of a whole list of nations—the Chechens, the Crimean Tatars, the Volga Germans, and many others—had been genocides, and the Circassians' tragedy was every bit as bad. But the Russian Parliament took those votes when its deputies included Soviet-era dissidents. By 2005 those justice seekers were long gone, however, replaced by party hacks in expensive suits, and Berzegov's petition brought him nothing but threats and harassment.

But his example inspired other Circassians to stand up. After the International Olympic Committee chose Sochi in 2007, Circassians around the world appealed the decision, but the IOC refused to reconsider. Asked for an explanation, the IOC's media director replied to Newsweek in an email: "Our philosophy is that hosting the Olympic Games can help bring positive developments in host countries and also be a catalyst for constructive dialogue. The IOC's role is to ensure the Olympic Games are of excellent quality, while remaining relevant and ensuring they deliver a long-term legacy to host cities. We believe that through sport we can achieve a lot but cannot resolve all the issues that a country might face."

Nevertheless, the Sochi Games give the Circassians a unique chance to mobilize their scattered nation. "We, whose fathers were subjected to genocide, once again underline that we condemn in the strongest terms the IOC's decision," said a statement from the Circassian group No Sochi 2014, which includes activists from Israel, Turkey, Jordan, Germany, France, and Belgium, as well as the United States. "Don't give the torch that the freedom lover Prometheus fired in the Mountains of Caucasus to the murderer of liberties, Russia."

As the movement gathered momentum, the Russian government launched a counterstrike. Leading the charge was one of the Kremlin's most trusted spin doctors, Margarita Simonyan, editor of the state-owned English-language Russia Today channel. An episode of her television show What's Happening, broadcast in April last year, mocked the outcry. Simonyan listed Sochi's real problems as traffic, traffic, and sewage. Then she displayed a graphic supposedly proving that since wars have been fought all over the world, the Games should not be held anywhere, after which she opened a satellite feed to an American foreign-affairs analyst, only to grill him about the weather in Washington.

She followed this performance with a furious blog post. The opponents of the Sochi Games were guilty of "clear, intentional, premeditated anti-Russian activity," she wrote. "We are talking about international hypocrisy, about loathsome attempts to rock first one, then another of our Russian ethnic boats, under the cover of concern for small nations. I do not like it when former CIA agents ... argue with sad expressions about the fate of a nation whose name they only heard the day before yesterday."

Simonyan's attacks only strengthened the Games' opponents. A video of her show was emailed throughout the Circassian community, snowballing anger and disbelief as it went. Amid the furor, Russia's Duma—the lower house of Parliament—finally agreed to meet with a handpicked group of moderate Circassian activists, and, shortly before last year's May 21 protests, a small group of deputies formally received a list of Circassian demands. Once again the campaigners called on the Russian government to acknowledge that what happened in 1864 was a genocide. But more than that, they called for the repeal of all laws preventing ethnic Circassians from moving back to their ancestral homeland, and they demanded that Russian authorities cease interfering in Circassian organizations. Everyone involved must have understood that the session was an empty formality.

Speaking to me after the meeting, Sergei Markov, a Duma deputy and historian, readily conceded that "mass killings" of Circassian civilians had taken place. He told me he had studied many books about their history. Even so, he insisted, anyone who believes there was a Circassian genocide is either illiterate or has sold out to an anti-Russian conspiracy. "The question is being awakened by those who want to make Russia weak," he told me. "They want Russia to always have to fight in the Caucasus, to explode the Circassian bomb." Markov has a history of spotting anti-Russian plots. At the time of the 2008 war between Georgia and Russia, he argued that it had been ordered by Dick Cheney to help John McCain's presidential campaign.

In fact, the Circassians are finding allies among those with grievances against Moscow. A year ago the Georgian Parliament voted unanimously to recognize the conquest of Circassia as a genocide, the first country in the world to do so. This May 21 the Georgians are taking their campaign a step further, unveiling a Circassian genocide memorial in the town of Anaklia, some 200 kilometers down the coast from Sochi and, not coincidentally, practically next door to the Kremlin-backed breakaway Republic of Abkhazia. Meanwhile the Circassians' own protests grow bigger every year. "A lot of our friends say that it's almost 150 years and that we should move on," Allan told me. "But they don't understand. For us it's like yesterday."

"I second that," said Danyal.

"I third it," said Clara.

Even if they can't stop the Sochi Games, they intend to use the occasion to tell the world their people's story. And for the first time in a century and a half, that will put the Circassians back on the front pages.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.