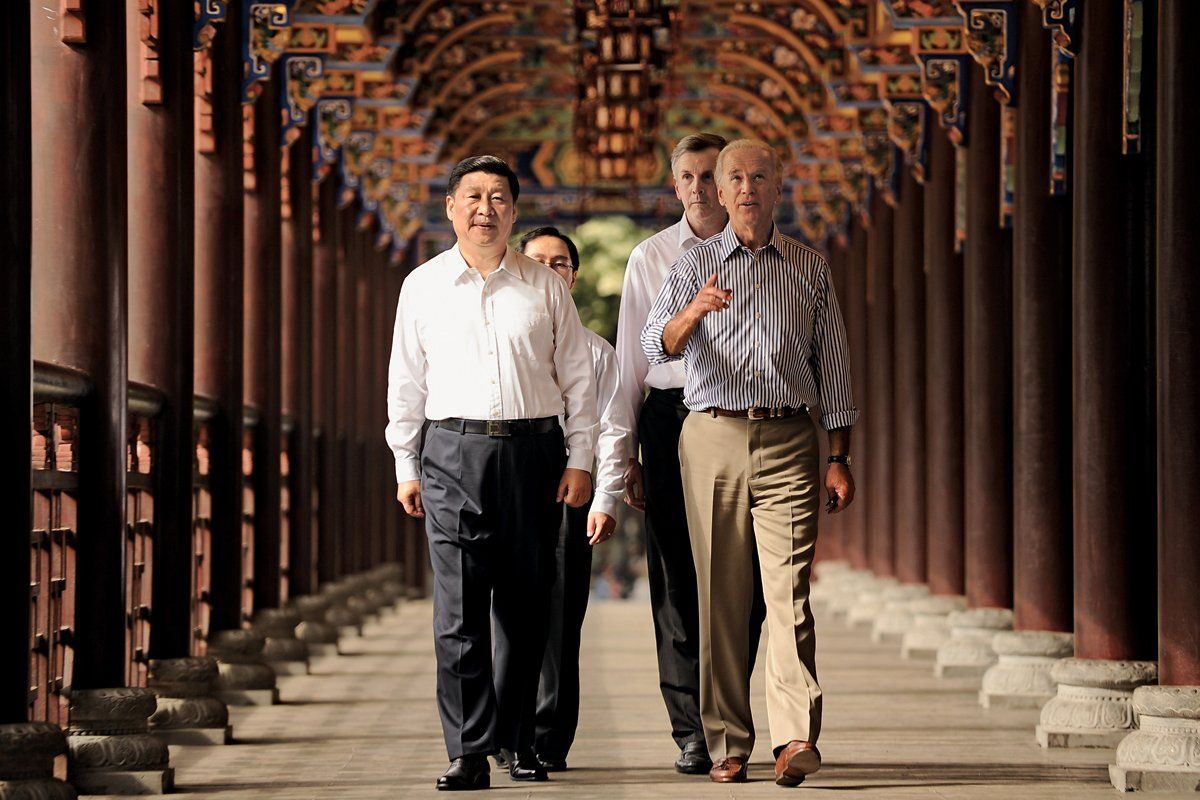

When U.S. Vice President Joseph Biden visited China last August, he spent many hours bonding over tea with his Beijing counterpart, Vice President Xi Jinping. At one point in their talks, Xi told Biden that his father—a former vice premier—and relatives had suffered during China's chaotic Cultural Revolution, a candid acknowledgment that things had gone horribly wrong during the country's bad old days. The official Chinese interpreter apparently was so flummoxed by Xi's comment that he never translated it into English, according to an informed source. Such eyebrow-raising candor is rare among Chinese apparatchiks. But "Xi communicates quite easily with foreign leaders," said one European diplomat who met him last year, "He's quite critical about the Cultural Revolution, saying there were mistakes made. I found that striking."

Xi, the heir apparent for China's top party post and the presidency, is the first among equals in a younger generation of Chinese leaders poised to take center stage during the Communist Party's massive transfer of power this year. The fresh crop of mandarins is more outspoken, individualistic, and self-promoting than the old crew. They are the nation's first "modern" politicians and pose a startling contrast to the elder generation of gray, straitlaced bureaucrats. But the fact that Xi and his colleagues are more personality-driven means they are less predictable—and more likely to make waves at home and abroad.

Right now Sinologists are scrutinizing who's up and who's down in China because the coming succession will signal a profound generational shift. The so-called Fifth Generation of officials, led by Xi, will move up in what's slated to be the biggest political turnover in the history of the People's Republic of China. During this autumn's 18th Party Congress, more than 60 percent of personnel will change within the 370-member Central Committee. This leadership game of musical chairs also means key players in the nation's economic and financial administration, foreign policy, public security, and military operations "will be mostly newcomers after 2012," says Brookings analyst Cheng Li, who specializes in Chinese politics.

Such a massive transition is rare in China—it's happened only three times since 1949. The first, during the 1960s, ended in purges, widespread persecution of intellectuals, and the anarchy of the Cultural Revolution. The second in the late 1980s unraveled when top leaders disagreed over whether to use force to disperse youthful protesters in Tiananmen Square; bloodshed followed. The most recent shift, when current party head Hu Jintao succeeded Jiang Zemin in 2002, was an impressively stable transfer of power. But that was the Communist Party's only succession plan that went according to script.

Now, in the run-up to the 2012 transition, the party is composed of two increasingly competitive coalitions, referred to as "populists" and "elitists." The populists, led by President Hu, rely on a powerful nationwide network of cadres in the Communist Youth League; their policies aim to ameliorate the growing gap between China's have and have-nots, which is most pronounced in China's impoverished western regions. Elitists are known for their free-market economic views and favoring coastal export industries; they include many "princelings" like Xi who are offspring of former high-level cadres.

The unusual nature of this rivalry was evident in the way Xi became heir apparent during the 17th Party Congress in 2007. To ensure continued political dominance by the populists, Hu had handpicked a different heir, Li Keqiang. But the elitist camp objected to Li, hoping to find a compromise candidate with greater neutrality. The choice was determined by a secret intraparty poll among grassroots and senior cadres, says political commentator Li Datong, and it turned out that Xi "got the highest vote." (Li Keqiang wound up being tipped to become premier in the reshuffle.) It was a face-saving solution, and a unique one: Xi essentially won a popularity contest.

In some ways, Xi has been on a leadership trajectory his entire life. He was born in 1953 as a classic "princeling," growing up as a child among the serene pavilions and heavily guarded crimson gates of Zhongnanhai, the compound where senior Chinese leaders reside. His father, former vice premier Xi Zhongxun, is best known as the architect of China's wildly successful and quasi-capitalist "special economic zones," launched more than three decades ago in the era of Deng Xiaoping's market-based economic reforms. But life wasn't without its perils for the Xi family. Xi senior was purged three times under Mao Zedong and spent 16 years in detention, much of it in solitary confinement, during the 1966–76 Cultural Revolution. (According to unconfirmed Chinese media accounts, Xi's half-sister died during the Cultural Revolution, prompting one of the few episodes when he publicly shed tears.) Xi "recognizes the injustice and the travesty of leftist totalitarian ideology during the Cultural Revolution," says author Robert Kuhn, who has written about China's top leaders and has met Xi. "But you don't see bitterness."

Xi was 9 years old when his father was first detained. Several years later, he joined millions of other urban youth "sent down" to rural communes for a stint of manual labor. "He was one of the first youth sent to the countryside," says Kuhn, "Ironically, it was good for him. It gives him some distance from the princeling label. In general, princelings don't fare well in the public perception."

Far from the comforts of Beijing, Xi arrived in hardscrabble Liangjiahe village, in Shaanxi province in January 1969, lugging "a whole box of books" with him, remembers current Party Secretary Shi Chunyang. Within five years, Xi had joined the Communist Party and embraced life on the farm. Learning that peasants in a neighboring province were using biogas to fuel their stoves, he traveled there to buy up the requisite hardware and transported it back to Liangjiahe. The sight of a princeling working with pig manure so impressed his rural comrades—or so the story goes—that they made Xi their village party head and recommended that he be allowed to attend university, "which was unheard of at the time," recalls one retired official who knew Xi in the '80s. Farmers gathered to bid farewell to Xi, and he set off to study chemical engineering at Tsinghua University, China's MIT. After his departure, Xi kept in touch with some of his peasant comrades, sending money to one who'd broken his leg. Later, when asked about his rural experience, Xi responded, "It was emotional."

Mao's death in 1976 ushered in an era of reforms, and Xi's family was back in favor. In a move that supported his own political ambitions, Xi served as personal secretary to Defense Minister Geng Biao, a former subordinate of his father. He then worked his way up through provincial postings, where he was known as the guy who got things done. During a 17-year stint in Fujian—right across the narrow strait from Taiwan—he coined the slogan mashang jiu ban ("do it now"), boosted cross-strait trade, and bonded with Taiwanese executives. He even reportedly became golfing buddies with a retired Taiwanese official. As a vice mayor of Xiamen in 1987, he impressed visiting politicians by wearing a casual windbreaker instead of a Western-style suit, and riding in a minibus instead of a chauffeur-driven car. "He was unusually easygoing, warm, and down to earth," recalled one of the visitors.

Xi's reputation continued to grow when, in 2002, he moved to Zhejiang, a province known for entrepreneurial wheeling and dealing. The thriving nature of Zhejiang's private enterprises—comprising nearly three quarters of the province's GDP—impressed then–U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson during a 2006 visit. Paulson met Xi and declared him "the kind of guy who gets things over the goal line." American author Kuhn recalls that when he met Xi, "he had a real spark."

Xi also struck Biden and other Americans as a leader with whom the U.S. can work—a standing that's bound to serve him well this month when he embarks on his first official trip to the U.S. For his part, Xi recently remarked that "our commitment to the development of the Sino-U.S. cooperative partnership should never waver in the face of passing developments."

"By no means can we let relations again suffer major interference," he said.

The biggest trick of Xi's presidency could be balancing a friendly relationship with Washington against China's complex domestic politics, in which nationalistic voices play a burgeoning role. Already, analysts believe he's had to counter the perception that he's too pro-Western; they point to a 2009 visit to Mexico in which Xi went off-script to slam countries trying to pressure Beijing, at the very moment when Washington was prodding China to revalue its currency. Complicating matters, Xi will need the support of China's generals "to consolidate his power," says China analyst Willy Wo-Lap Lam. "This means the generals will have an even bigger say in foreign policy. [And] we've already seen many examples showing the generals aren't too happy with a closer relationship with the U.S."

Will Xi be able to bridge the rifts within his own party? His princeling roots and free-market prowess make him appealing to the elitists, while his years on the farm make him more acceptable to the populists, many of whom spent their careers in the hinterland. Xi's also perceived to be clean; at least twice he's cleaned up after provincial corruption scandals that ensnared his predecessors. He's seen as a leader whose Cultural Revolution experiences taught him the importance of humility and adaptability. "These are his strong points," says Brookings analyst Li. "He's also more spontaneous and less calculating than many of his peers." And his image is "helped tremendously" among ordinary Chinese by his wife, superstar People's Liberation Army singer Peng Liyuan, who is possibly more famous than her husband.

But Xi is hardly invincible. China faces alarming levels of inflation, a risky property bubble and massive local-government debt. Xi and his new team will face a steep learning curve—and his status as a compromise character means he lacks the institutionalized political backing that some of his rivals can mobilize. "Xi lacks his own people in senior positions in the party," says Li. "In some ways, he's very much on his own."

With Isaac Stone Fish.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.