Leaking diplomatic dispatches used to be a recognized diplomatic art. In the not too distant past, American ambassadors in Central America or the Middle East who thought Washington was ignoring their cables would share them with correspondents, knowing that news reports would have a better chance of reaching the secretary of state's desk than almost any memo the ambassadors wrote themselves.

The very essence of diplomacy between nations in the old days—maybe even yesterday—lay in knowing the difference between official communications, unofficial ones, and those that, being leaked, might be denied. (During the American Civil War, the U.S. secretary of state once read a confidential dispatch word for word to the correspondent for the London Times, just to make sure the British foreign secretary got his point ... unofficially.) All of these modes had their uses for signaling intent, saving face, or stepping back from a brink. And they still do, as the 250,000 U.S. State Department cables that have begun appearing on Wikileaks.ch amply demonstrate.

Inside State, in the ferocious competition for the attention of the secretary, candor and accuracy were also part of the game. Cables with pithy descriptions of Russia's president and prime minister as "Batman and Robin" are more likely to be read than those that are blandly academic. And who can forget the cable describing Libyan leader Muammar Kaddafi's Ukrainian nurse who travels "everywhere with the leader." "The guy who wrote this had it nailed!" says a veteran CIA officer who read the Kaddafi dispatch. "Without this kind of writing, the cables would be dull as butter."

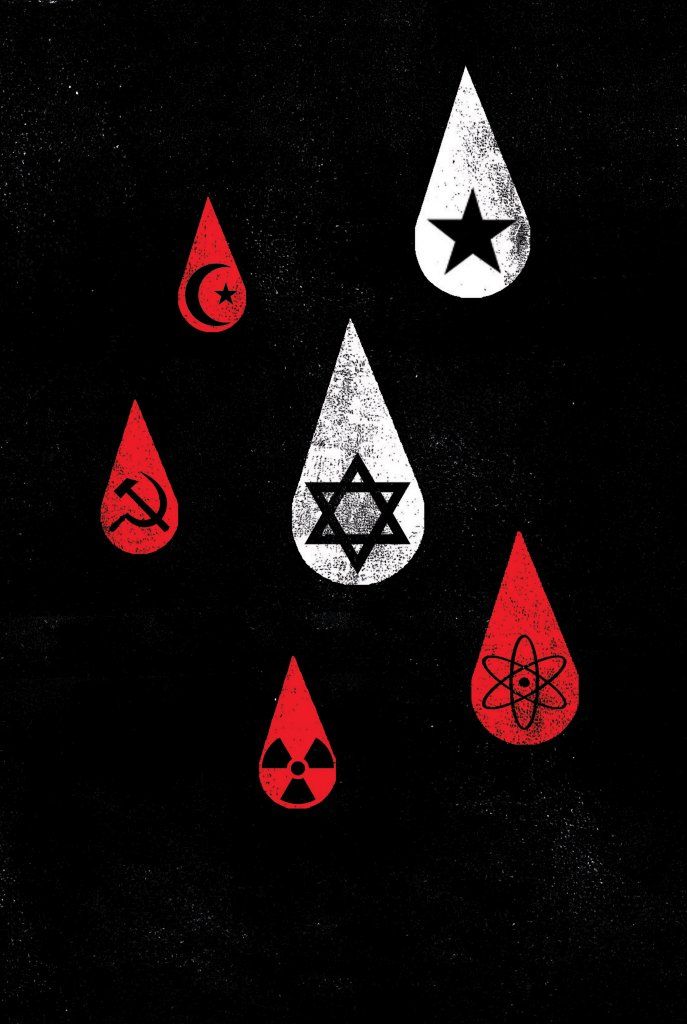

One of the great ironies of the latest WikiLeaks dump, in fact, is that the industrial quantities of pilfered State Department documents actually show American diplomats doing their jobs the way diplomats should, and doing them very well indeed. When the cables detail corruption at the top of the Afghan government, the Saudi king's desire to be rid of the Iranian threat, the personality quirks of European leaders, or the state of the Russian mafiacracy, the reporting is very much in line with what the press has already told the public. There's no big disconnect about the facts; no evidence—in the recent cables at least—that the United States government is trying to deceive the public or itself. And when it comes to taking action, far from confirming the increasingly commonplace image of a waning superpower and a feckless State Department, the WikiLeaks cables show that American diplomats draw on the full range of tools at their disposal, the soft power of persuasion and the hard power of economic and even covert military action, especially in the fight against Al Qaeda.

"Diplomacy is about a mix," says Joseph Nye, a former head of the National Intelligence Council, who coined the term "soft power." "The cables reveal how effective most American diplomats really are." Do they always get what they want? No. There are endless compromises and work-arounds. But Harvard's cold-eyed realist Stephen M. Walt notes that the cables leaked so far show that, still, "everybody around the world wants Uncle Sucker to solve their problems." As Walt wrote on ForeignPolicy.com, "It is still striking how many pies the United States has its fingers in, and how others keep expecting us to supply the ingredients, do most of the baking, and clean up the kitchen afterwards." Sir Christopher Meyer, former British ambassador to Washington, suggests with typical reserve that "the chaps in the field are doing pretty well," while Roger Cohen, the veteran foreign correspondent and columnist for The New York Times, is absolutely frank in his admiration for the people writing those cables: "Let's hear it for the men and women of the U.S. Foreign Service!"

But there's also a real risk that this slow-motion avalanche of 250,000 documents, 11,000 of them classified "secret," will diminish or destroy the nuance at the heart of the diplomatic arts. The founder of WikiLeaks, Australian computer hacker Julian Assange, claims he's acting in the interest of "justice" and "transparency." "I enjoy helping people who are vulnerable," he told Der Spiegel last summer, "and I enjoy crushing bastards." But Ryan Crocker, the U.S. ambassador who helped pull Iraq back from the edge of total chaos in 2007, sums up a common view among diplomats when he says, "Assange is an anarchist—he's not really interested in getting at important policy issues—just expose it all."

Assange finds discretion suspect, as if its sole purpose were to conceal information. And it is certainly worth considering that argument, given the way some American administrations used secrecy to lead the public astray with tragic consequences in Vietnam, Nicaragua, and Iraq. But, in fact, the WikiLeaks documents revealed so far show diplomats doing just the opposite: using their reporting skills to try to illuminate the complexities of the countries where they serve, and their negotiating skills to reduce the threat of war, whether with North Korea or in the Middle East.

The Iranian case offers the most detailed and complex picture of American diplomacy revealed by WikiLeaks so far. China, Russia, Turkey, Arab allies, and European partners are all part of the picture. To push tougher sanctions on Iran through the U.N. Security Council, for instance, the United States had to bring Beijing on board. But China looks to Iran for critical supplies of oil. So the Obama administration went to the Saudis. Did King Abdullah want Uncle Sucker to "cut off the head of the snake" by unleashing a military strike? Well, maybe it would be smarter for Abdullah to guarantee oil for China if Iran threatened to cut off the supply following China's approval of tougher sanctions. The deal was sealed. As president emeritus of the Council on Foreign Relations Les Gelb sums up the strategy: "If the world wants to slow or even prevent Iran's march to nuclear weaponry, this is a key path to doing so."

Despite the barrage of headlines shouting over how sour their relationship has become, the cables reveal Washington and Moscow working on intimate terms to blunt Iran. The account of an exchange between top Russian and American officials in February paints a portrait not of Cold War–era adversaries who can barely sip vodka together, but of intelligence comrades cooperating closely. In Washington, a member of the Russian Security Council offered a senior State Department official an analysis of Iran's latest efforts to improve the accuracy and range of its medium-range Shahab-3 ballistic missiles. A ranking member of the FSB (Russia's intelligence service) recounted how his agency uncovered sham companies set up by both Iran and North Korea to buy military hardware such as "measuring devices, high precision amplifiers, pressure indicators, various composite materials, and technology to create new missile engines." What's clear from such cables is that the much-discussed "reset" of American relations with Russia has gone far deeper than just about anyone outside government understood.

The campaign to isolate Iran continued in Turkey. Also in February U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates, whose CIA background includes a lot of diplomacy, met with his counterpart in Ankara. In the run-up to the meeting, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan had made public statements playing down concerns over Iran's nuclear ambitions, saying they were just "gossip," but in the private talks with the head of the Pentagon, the Turkish defense minister, Mehmet Vecdi Gonul, dispensed with the posturing. Ankara was "concerned about the Iranian threat," he said. And contrary to public statements by Turkish officials playing down the need for a Europe-wide missile defense shield, the Turks and the U.S. appear in the cables to be horse-trading over possible sites for a program on Turkish soil.

Gates pushed the point. He told the Turks that there was "a good chance" the Israelis would take it upon themselves to strike militarily against Iran, and suggested that Turkey might want to bolster its own defenses against Iranian retaliations—a position much more alarmist than any senior American official has taken in public, but also one useful to encourage tougher action by Ankara.

Has this diplomacy been successful in stopping Iran's nuclear program? Not so far. But it may well have helped avert a war. Back in June 2009, Israeli Defense Minister Ehud Barak was quoted in another of the leaked cables saying there were only six to 18 months left for military action that could stop or stall the Iranian nuclear program. That deadline is now upon us, but the war is not. Of course, covert action, presumably including the introduction of the ultrasophisticated Stuxnet virus into Iran's computers, has also slowed the program, but that's not covered in the WikiLeaks cables.

Indeed, the sheer volume of the WikiLeaks trove tends to give the impression it's a complete picture of American diplomacy when, in fact, it's not. Thus even The New York Times concluded that the cables at its disposal showed a lack of depth, and a paucity of contacts, in the American reporting from Moscow. At one level that may be true. But, then, the Times makes no mention of the fact that one of Russia's most important spymasters defected to the United States last summer, since the highly secret circumstances surrounding that case are not included in Assange's relatively low-level dump.

One of the most sensitive pieces of information that did get exposure last week was about what's already been reported in the press as a covert CIA program targeting Al Qaeda in Yemen from the air. It's not really a secret that Yemen's President Ali Abdullah Saleh has allowed this to go on, but he needed to be able to deny it for internal political reasons. In many cultures in the world, lies are acceptable, even when they are known to be lies, as a way to avoid showdowns. But now we have Saleh quoted in an official State Department cable telling U.S. Gen. David Petraeus last January, "We'll continue saying the bombs are ours, not yours," followed by Yemen's deputy prime minister joking about lying to the Yemeni Parliament. "That sort of thing strikes right at the heart of a covert-action program where deniability is such an important thing," says Michael Sheehan, a former State Department ambassador-at-large for counterterrorism.

In the wake of such revelations, we can expect to see—or rather not see—even more diplomatic traffic hidden away at higher classification levels. Ever since the September 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States, the government has been fighting to break down the bureaucratic walls among agencies. Until then, they kept their information in figurative "silos" or "stovepipes," and often refused to share. That created massive blind spots that helped open the way for Al Qaeda to attack. Since 9/11, some cable traffic has been distributed much more widely. But in the wake of WikiLeaks, efforts already are underway to curtail that practice. Last week the State Department reportedly cut off the U.S. military's access to its Secret Internet Protocol Router Network, known as SIPRNet, which is believed to have been the opening exploited by the leaker feeding cables to Assange. And that's just the beginning of the internal lockdown. "Sensitive meetings will get smaller," says Sheehan. "Less will be said, and definitely less will be written. There will be a lack of candor. And all of that will increase the chance of miscommunication."

The good job that American diplomats have been able to do in the last few years will now get a whole lot harder.

With Owen Matthews in Moscow, John Barry in Washington, William Underhill in London, R. M. Schneiderman and Mike Giglio in New York

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.