I swear, if anyone ever releases a photo of me taken after I'm dead, they should be prepared for a lifetime of paranormal activity—the Poltergeist kind. That said, I must admit I've looked at pictures of dead people myself. (Skip the moral outrage.) I'm just saying that if the alleged pictures of a dying Gary Coleman are published (and if they exist, they will be), it'll just be another addition to the mausoleum of celebrity corpses already on permanent display on the Web.

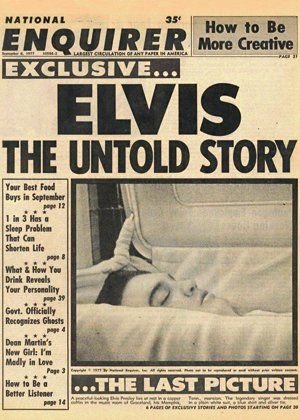

Celebritymorgue.com is one of the fanciest, with photos of the deceased Marilyn Monroe, Kurt Cobain, and Elvis Presley—not to mention a disturbing number of dead historical figures. But there are plenty of lesser sites out there, too. I was too squeamish to look—honest I was!—but when I Googled "pictures of dead people," I got 200 million results. "Pictures of naked people" only got 20 million.

Maybe that's not scientific, but you see my point: we have a love-hate relationship with death. Anytime a photo such as the one of a dying Michael Jackson makes the rounds, or when autopsy photos of Marilyn Monroe or JFK are stolen, or when police photos from the Ted Bundy files show up on eBay, or every time somebody tries to steal Elvis's corpse, the lecture is always the same: stop grave digging. Let the dead lie in peace. In Coleman's case, we'll hear "Why didn't we care this much about this D-list star when he was alive?"

The imagery of death is kept hidden now, but it wasn't always so. After the invention of the daguerreotype in 1839, 19th-century families regularly took photos of their dearly departed as remembrances. We'd call that macabre, but death was a more integrated part of life then. Newspapers regularly published pictures of dead bad guys like John Dillinger. At the viewing of bank robbers Bonnie and Clyde, people ripped off pieces of their clothing and cut their hair for keepsakes. Life magazine printed the picture of a woman after she jumped to her death from the top of the Empire State Building and landed on top of a car in an almost peaceful repose. Imagine that happening now, when we remove pictures of the World Trade Center from old television shows and debate whether the flag-draped military coffins can be photographed by the press. In 1955, Mamie Till insisted that her son, Emmett, be photographed in an open casket, so that her son's murder would force people to look at the horror of racism. Would anyone publish that undoctored photo today? Before you answer, remember: many folks objected when magazines (including NEWSWEEK) published pictures of a dead Saddam Hussein and his equally dead sons.

Maybe the scolds are right; maybe limiting images of death saves us from morbid curiosities. But I don't think it does. The tabloid that reportedly bought those pictures of Coleman did so because of our culture's fascination with death—anyone's death. They know we may hold our nose, but we'll look at them. We can't help ourselves. When people buy that paper, they'll be motivated by the same urge to slow down for a better look at a car crash. Everyone seems to want a glimpse of the fate that scares us the most and that none of us will escape. How is looking at the body of Che Guevara or Gary Coleman any different from the hours we spend watching autopsies on CSI? We want to see it almost as much as we say we don't. Freud called this need to flirt with the idea of your own mortality the death drive, sort of like having a fascination with heights but an obsessive fear of falling. If Freud is right, that "the aim of all life is death," then it's no wonder we are so curious about the faces and shapes of celebrity death. We are a culture that sees itself in the stars, and spying on a dead actor is a way to consider our own mortality from the safety of our living rooms.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.