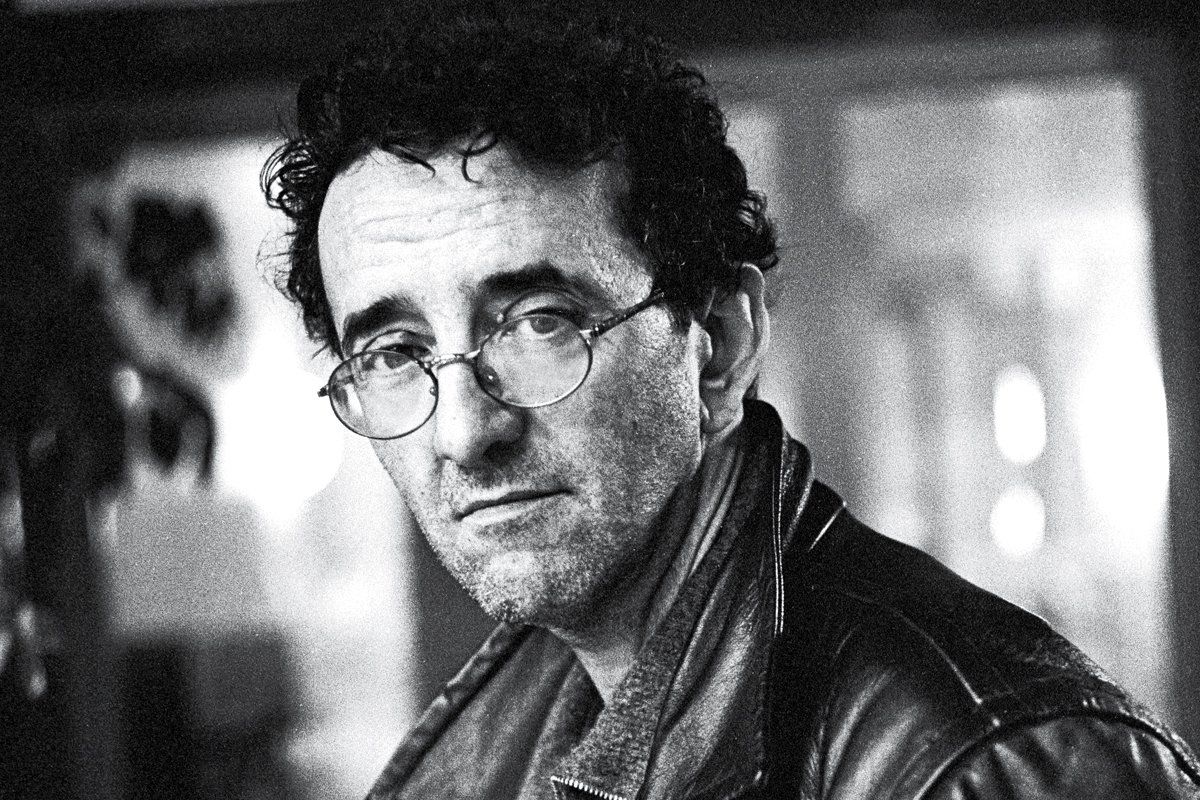

Asked once what he might have been if he hadn't taken up writing, Roberto Bolaño didn't hesitate. "A homicide detective," he said. "I would have been the sort of person who comes back alone to the scene of a crime by night, unafraid of ghosts." That was his last interview, granted in 2003, weeks before he died of liver failure at age 50. No one knows what the Chilean author's ghost has been up to since, but he's certainly still haunting Latin American literature.

How to explain that the most celebrated Latin writer since Gabriel García Márquez and Octávio Paz has been dead for nearly a decade and yet has published more posthumously than most authors manage in a lifetime? A respected novelist while alive, in death Bolaño has soared to cult status, translated globally, with stories rolled out in The Paris Review, The New Yorker, and The New York Review of Books. A Facebook page devoted to Bolaño boasts 43,000 fans and a feature film, El Futuro, based on one of his short stories, is in production.

Dying young can increase an artist's cachet, but in Bolaño's case, that's not what has bewitched the critics and set the gears of canon-making in motion. Bolaño was a rare and luminous talent in an uneven and often dull literary landscape. A frustrated poet, he turned to prose in his 30s to pay his bills—and shone. Many of his novels may seem facile, packed with talky introspection and postpubescent brooding, but in fact are densely layered tales, with scores of narrators, soaked in erudition and mordant social comment. A ferocious reader, Bolaño wrote with Cervantes, Dante, and Homer looking over his shoulder. The poet protagonists of The Savage Detectives, who launch a grail-like quest across the Mexican desert, are named Ulises and Arturo. And yet Bolaño's writing is always direct and wry, uncluttered by ornament or cliché—a blessing in a region taken with rococo flourishes.

The fuss over Bolaño began last decade with the world debut of 2666, an 1100-page epic, by turns comic and brutal, which roams from World War II-era Eastern Europe to a drug-infested Mexican border town hauntingly like today's Ciudad Juárez. Bolaño had abandoned the novel when illness overwhelmed him, but his family salvaged the manuscript and allowed it to be published in 2004 and translated into English four years later. It is now hailed as the author's masterpiece.

Last year tomb raiders turned up The Third Reich, a compact novel written by Bolaño two decades ago but forgotten in a drawer. Now comes The Secret of Evil, a collection of essays and short stories out on April 24. Some of the entries have been published before and others are barely more than sketches, but there are gems in the scrapings. "Scholars of Sodom," an admiring but also severe take on V.S. Naipaul's legendary visit to Argentina, is well worth the $23 cover price. Given the fevered pace of his later years, no doubt the Bolaño factory is scouring the estate for even more of his oeuvre.

And no wonder. Bolaño had few equals in Latin America, or beyond. A ventriloquist, he switched countries and voices with uncanny ease as he wandered from his native Chile to Mexico, France, and Spain. Udo Berger, the antihero of The Third Reich, is a German vacationing in Spain, whose only allegiance is to a remote web of international war-games aficionados. Bolaño had no patience for claims of national identity. "Books are the only homeland of the writer," he wrote.

That indifference to place and community trampled on Latin American literary conventions. Starting in the 1960s, García Márquez, Paz, Mario Vargas Llosa, and others electrified millions of readers with vivid stories immersed in Latin history and culture; their tales erased the lines between the real and the fabulous. El Boom, as the Latin renaissance was called, had played itself out by the 1990s, except for some kitschy imitations. But the search for the next boom has never ceased.

A klatch of young writers gave it a shot last decade with the McOndo movement, a send up of Macondo—the mythic village in García Márquez's One Hundred Years of Solitude—conflated with McDonalds, the ultimate symbol of globalization. Then came El Crack, a nervous genre inspired by the jarring, hyperurban reality of modern Mexico City. Their shared goal was to overthrow the folksy, exotic idyll of magical realism that had put Latin American letters on the map but also in a straightjacket. The new fiction was cheeky and occasionally brilliant, but it failed to trump the masters. The anti-Boom ended in a fizzle.

A new generation of writers has retreated even further from the Latin tradition. The talented Jorge Volpi, of Mexico, has written acclaimed books about the Paris of Jacques Lacan and the quest by German scientists to make the atom bomb. Many write magnificently but eschew grand themes of history, place, and politics for the bonsai-sized universe of the soul. Chile's Alejandro Zambra and Bolivia's Rodrigo Hasbún are poetic minimalists. Gabriela Wiener's Sexografías was inspired by a visit to swing clubs, while Ghosts, by Argentina's César Aira, is about zombies. It's as if fiction had been stripped of context and "enlisted into the armies of the Mini-me," Bolaño once despaired.

Roberto González Echevarría, a Yale scholar, traces the shrinking scope of post-Boom writing to the collapse of the Cold War. Down with the Berlin Wall came the grand Marxist "narrative" that had served as a "secular religion" to Latin America. Or perhaps fiction itself has suffered a downgrade. "Bolaño comes at a time when people read less, watch [more] television and surf the Web," says Ilan Stavans, an Amherst College professor of Latino studies. "Literature has lost its urgency."

Bolaño was no political pamphleteer. And yet his characters' angst and desires play out against the canvas of history. With his raw, barely controlled emotions, and a talent for mining the pathos, beauty, and even humor amid the horror of ordinary life, his fiction soared. "Bolaño is a kind of medicine against the trite and commonplace in this mass-market-driven world of literature," says Stavans. That alone has won Bolaño an honored place in the afterlife.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.