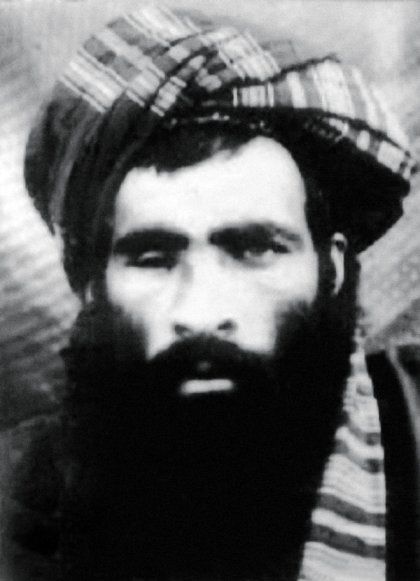

A thrill coursed through the Taliban's ranks a few weeks ago—someone was said to have seen a new video that showed Mullah Mohammed Omar in the distance, firing a Kalashnikov. The insurgents rejoiced: they hadn't heard from their reclusive leader since late 2001, when he rode east into the Kandahar mountains on the back of his brother-in-law's motorcycle, fleeing a storm of U.S. bombs.

The excitement, however, quickly evaporated. No one recalls how many times Mullah Omar has supposedly reappeared over the past nine years, but it always ends the same way: the rumored new video, signed communiqué, or audiotape turns out to have been a fantasy spawned by careless talk and fervently wishful thinking. Then the nagging questions start again: Where is Mullah Omar? Is he alive? Is he in charge? And if not, then who is?

A clear answer to those questions would very likely decide whether the Afghan insurgency stands or falls. Everyone agrees that absolute loyalty to Mullah Omar is what holds the Taliban together. Practically to a man, the group's commanders and fighters say they're fighting for the village cleric they call the Amir-ul-Momineen—the "commander of the faithful"—and for the restoration of his Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. "Every Taliban knows that the morale and unity of the insurgency depend on Mullah Omar," says a senior Taliban intelligence officer, asking not to be named for security reasons. "We are all fighting for him." Without their faith in Mullah Omar's divinely inspired leadership, the Taliban would almost surely collapse into a welter of rival clans and factions.

Those splits are more visible now, as the doubts and divides grow with every false report. Nearly a dozen Taliban commanders who were interviewed by NEWSWEEK for this story say Omar's silence has become an urgent topic among the Taliban leadership. Most of their rank-and-file fighters remain convinced that Omar is alive, in charge, and guiding the insurgency, they say. But that's partly because the commanders themselves keep the legend alive and partly because any suggestion in the ranks that Omar is dead, or not in control, might brand the speaker as a nonbeliever, perhaps even a spy. "Asking about Mullah Omar's whereabouts raises suspicions and is prohibited," says the senior Taliban intelligence officer. In private conversations, however, that's just what top commanders are doing.

It's hard to fathom just how this inarticulate village mullah has inspired such devotion. Aside from being an expert prayer leader and reciter of Quranic verses, there's nothing particularly impressive about him, says Pakistani journalist and Taliban expert Rahimullah Yusufzai. According to Yusufzai, who met and interviewed Mullah Omar 10 times before his ouster, the Taliban leader is devoid of charisma and displays no intellectual subtlety, viewing every issue in black and white. Even when he was in power, he rarely made public appearances and ventured to Kabul only once from his home in Kandahar.

Yet his followers speak of him in worshipful, almost needy terms. "As Muslims we believe in almighty Allah, but we don't think about what he looks like or where he is," says a senior guerrilla commander in Paktia province. "Similarly we believe Mullah Omar is with us even if we can't see or hear him." Some Taliban suggest his absence might even be a blessing. "We may not know where our amir is, but that means our enemies don't either," the intelligence officer says.

Nevertheless, the insurgency is suffering without him. Former aides to Mullah Omar are presenting themselves as would-be leaders, and no one is in a position to challenge them. Omar's onetime personal secretary Gul Agha claims to have a signed letter from the amir naming him as Omar's new deputy, after the arrest of Taliban No. 2 Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar earlier this year. But many commanders question both the letter's authenticity and Gul Agha's qualifications for the job. Another aide, former Taliban finance minister Agha Jan Mutassim, is trying to organize his own militia. He might have the money to do it, having been canned several years ago for allegedly absconding with $20 million in state funds during the regime's fall—a charge he strenuously denies.

And discipline is crumbling among hotblooded younger insurgents, their commanders say. A Taliban code of conduct has been issued in Mullah Omar's name several times, most recently last summer, ordering fighters to "avoid civilian casualties" even in attacks on high-value targets, but it's widely ignored in suicide bombings and IED attacks. More than 1,000 civilians have been killed this year, more than 60 percent of them by the Taliban. "Not everyone believes anymore that these orders are from Mullah Omar. That's why we can't stop these things," says Gul Ahmad, a subcommander in central Afghanistan. "Mullah Omar could make a difference with just one audio message," says the Paktia commander.

Skepticism is rising about practically every decree issued in Omar's name. Eighteen months ago an order allegedly signed by Mullah Omar surfaced, urging the Pakistani Taliban to cease attacking Pakistani military targets and to focus instead on fighting the Americans in Afghanistan. Many insurgents think the letter was written not by their leader but by Pakistan's Directorate for Inter-Services Intelligence. In fact, some senior commanders worry that the ISI may be holding Omar prisoner and issuing self-serving orders in his name. "Sometimes I suspect someone invisible is running this Mullah Omar show," says the Paktia commander.

Some even say the orders may be American forgeries. This past June, NATO officials in Kabul announced that Coalition forces had intercepted a message from Mullah Omar ordering his men to "capture and kill Afghan civilians, including women, working for foreign forces"—in direct contravention of the previously issued code of conduct. NATO's Brig. Gen. Josef Blotz says he's "100 percent sure" the letter was from Mullah Omar. Nevertheless, the Taliban—and at least a few independent analysts—think it's more likely part of a Coalition psychological-warfare campaign to discredit the insurgents in the eyes of Afghans.

Commanders fear that the insurgency, while growing, is skidding into confusion. "Somehow we have to restore order," says the intelligence officer. "The stronger we get, the more we need a leader like Mullah Omar." "We don't have an overall plan," complains Gul Ahmad. "We seem to be leaderless outside district and provincial levels." The three commanders who supposedly took over from Baradar after his arrest have gone underground for their own safety, according to Taliban sources, leaving a vacuum at the top.

Even sympathetic Afghans are starting to have doubts. "Villagers ask us the same questions that we are asking ourselves," the Paktia commander says. "?'Why don't we hear from Mullah Omar? What does he think? Where is he?' Our morale is hurt because we can't answer them."

Perhaps the enigmatic Mullah Omar—if in fact he's alive and at liberty—is waiting for the right moment to show himself. But meanwhile the cracks in his insurgency are deepening. Unless he surfaces soon, his hopes of returning to power could disappear as completely as he has.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.