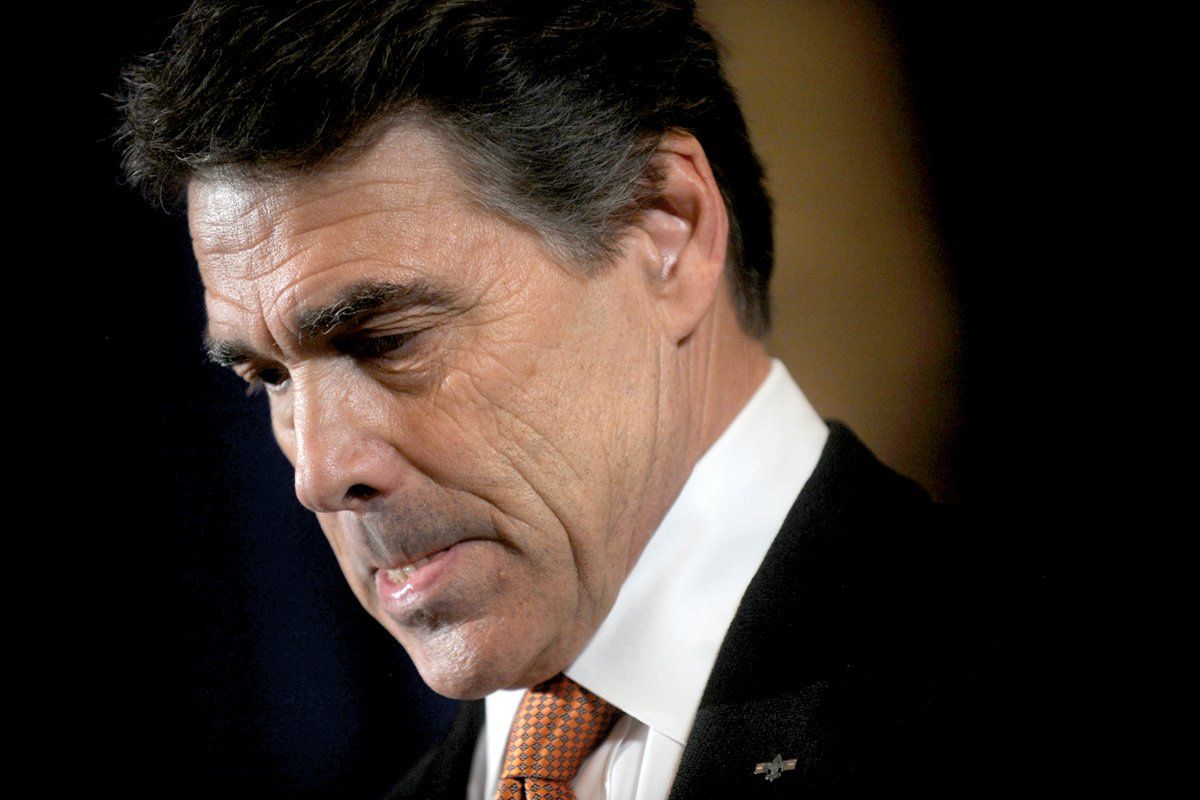

"I want to share one little story that happened to me," Rick Perry says, sounding almost wistful as he recalls a favorite moment from the early, exuberant days of his presidential campaign—just seven weeks ago.

On a sunny day in late August, Perry's campaign bus made an unscheduled stop in Gaffney, S.C., to give a ride to a local pol, state Senate Majority Leader Harvey Peeler, who'd been a key early supporter. "When we came around the corner to this little restaurant parking lot, there were probably a hundred-plus people there, carrying homemade signs," Perry says. "And so I just got off and dove into the crowd." Witnesses to the moment recall seeing Perry at his essence, the consummate political retailer—touching, listening, connecting as he worked the crowd. Perry noticed that one woman seemed particularly intent as he made his way toward her. "This is a person," Perry thought, "who's really excited about seeing what may be the next president of the United States."

The woman, Shellie Wylie, is a mother of two who runs a small travel agency in Gaffney. She'd come to ask Perry one thing: could he help struggling small businesses like hers? But when her moment came, she broke down, sobbing. Perry took Wylie in his arms and assured her that she would be all right. And Wylie believed. "It was a compassionate moment, one person to another," Wylie recalls. "That sincerity goes a long way. And he meant it." Wylie left that day a committed Perry supporter, convinced that he was the candidate to defeat Barack Obama.

It's understandable that Perry, in a recent conversation with Newsweek, would return to that day, which came near the high-water mark of his candidacy. Perry had been at it for only 10 days at that point; in another week, he'd built a double-digit lead over Mitt Romney in the polls. Then, just as suddenly, came the collapse. The confident, handsome Texan, who'd bounded onto the national stage with the swagger of a natural frontrunner, took his place on the debate circuit and turned into a tongue-tied tackling dummy for his competitors. Perry's ability to work a room or rouse a crowd was legendary, but onstage with a group of antagonists whose ambitions matched his own, he seemed unable to formulate intelligible sentences, much less coherent policy arguments. It was almost comically weird, like those recurring Seinfeld gags when Jerry's latest girlfriend is revealed to have some bizarre flaw ("She has man-hands!"), killing any hope of romance.

Perry's camp blamed his performance on the fact that he had gotten into the race late and hadn't yet found his groove and was keeping too rigorous a schedule. But Perry himself probably answered the question best after last week's smackdown, when he told reporters, "Debates are not my strong suit." It may have been the understatement of the political season.

The rationale for a Perry candidacy had been his promise as the anti-Romney; he was the longest-serving governor of that big red state where business prospered, jobs bloomed, and government got the hell out of the way. "Our most important attribute," he says of himself, "is to have been the chief executive officer that has worked with the private sector to create more jobs than any other state in the nation during the decade of the 2000s."

That message, the Perry camp knows, has been obscured by the candidate's stumbling performances onstage. Asked by Newsweek how he meant to prepare for last week's debate in New Hampshire—framed by the political press as his do-or-die moment—Perry said, "My job is to fend off the arrows, fend off the attacks, and to pivot back to what is obviously the most important issue to the America people: jobs." His campaign team prepped him hard for the exchange and made sure he got enough rest before the event. As it happened, Perry needn't have worried about fending off attacks—he was virtually ignored in the debate.

Right-wing disappointment in Perry was tartly expressed the next day by conservative radio commentator Mark Levin, who told his listeners: "I need somebody in a debate who's gonna sit up straight, look Romney in the eyes, and take the guy on. Is that too much to ask?"

The polls have reflected that view, with Perry's support falling in the Real Clear Politics compilation to the lowest point—13.7 percent—since he entered the race, trailing not only Romney but also the new star of the moment: the former bit player Herman Cain.

Perry's forensic infelicity has not only blunted his critique of Romney, but has exacerbated his own controversies. A sound conservative defense can be made for the Texas law, championed by Perry, allowing the children of illegal immigrants to attend college at in-state tuition rates, but Perry badly botched his chance to make it. Critics of the policy, Perry said, "have no heart," an assertion that infuriated many in the Republican base. "I readily admit that I made a harsh comment when I said that people were heartless if they did not accept the position that we felt," he says now. "That was incorrect. I shouldn't have said that." The argument Perry meant to make, he says, is that Texas was forced by flawed federal policies to deal with the children of illegal immigrants, and Texas chose to "make taxpayers, not tax wasters" of the youngsters by helping them get to college.

Perry has been criticized for coming to the presidential race without a real economic plan. He began to address that matter on Friday, when he delivered his first major policy address in Pittsburgh. As expected, the Perry plan for economic recovery calls for the aggressive exploitation of American reserves of fossil fuels through a series of executive orders and the easing of environmental regulations. This plan, which Perry claims will create 1.2 million jobs, poses a contrast to President Obama's green-jobs agenda, which seems to be coming a cropper—the jobs proving ephemeral and the process of creating them with taxpayer money potentially scandalous. (Critics will be quick to note that Texas's Emerging Technology Fund seems like a mimic of the Department of Energy loan-guarantee program that Republicans in Congress are now using to torment Obama.)

Perry can take some comfort in the fact that Romney still cannot get traction with the conservative base. "Mitt's record is, at best, muddled when it comes to issues that are important to Republican primary voters—whether it's social issues, whether it's economic issues, whether it's his record as the governor of Massachusetts," Perry says. "I think that is the reason there is somewhat of a ceiling for him, if you will."

Perry's aim is to somehow survive as the alternative to Romney. At the moment, the former frontrunner seems a decided long shot. By the end of last week, Perry had been overtaken by Newt Gingrich in a Rasmussen poll.

But the Gingrich rebound is itself instructive. He entered the summer a badly damaged candidate, abandoned by the core of his staff and hurt by his criticism of Paul Ryan's entitlement reform plan. Helped by strong performances in the debates, Gingrich has inched his way back to respectability. Perry lacks Gingrich's ability at political argument, but he has his own advantages: a big pot of money ($17 million) and the killer instinct required to prevail in a long string of Texas campaigns. "This is a long process. It's going to ebb and flow. We'll be up, we'll be down."

Perry has lived much of his political life in George W. Bush's shadow—he was elevated to the governorship when W. was elected president—and he does not want to return to Texas a loser. Perhaps what Perry most needs, and what his grueling campaign schedule will provide, is a return to the street campaigning he does best; he needs, figuratively speaking, to get back to Gaffney. Shellie Wylie is waiting.

"Ricky, you are still my choice," she wrote in a message to Perry last week, which she posted on his Facebook page. And she offered some advice: "If debating isn't a strong skill, then be as prepared as you can with facts, take a breath and a few seconds to answer if you need to. Still you should be speaking from the heart. That is what is currently missing from your campaign—the American people are not seeing who you really are."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.